Chinese influences on Islamic pottery

Right image: Iraqi earthen jar, 9th century, derived from Tang export wares. British Museum.

Left image: Brass tray stand, Egypt or Syria, in the name of Muhammad ibn Qalaun, 1330-40.British Museum.

Right image: Ming porcelain tray stand with pseudo-arabic letters, 15th century, found in Damascus. British Museum.

Chinese influences on Islamic pottery cover a period starting from at least the 8th century CE to the 19th century.[1][2] This influence of Chinese ceramics has to be viewed in the broader context of the considerable importance of Chinese culture on Islamic arts in general.[3]

Earliest exchanges

Pre-Islamic contacts with Central Asia

Despite the distances involved, there is evidence of some contact between eastern and southwestern Asia from antiquity. Some very early Western influence on Chinese pottery seems to appear from the 3rd-4th century BCE. An Eastern Zhou red earthenware bowl, decorated with slip and inlaid with glass paste, and now in the British Museum, is thought to have imitated metallic vessels, possibly of foreign origin. Foreign influence especially is thought to have encouraged the Eastern Zhou interest in glass decorations.[4]

Middle image: Earthenware jar with Central Asian face, Northern Qi 550-577.

Right image: Northern Qi earthenware with multicultural (Egyptian, Greek, Eurasian) motifs, 550-577.[6]

Contacts between China and Central Asia were formally opened from the 2nd to 1st century BCE through the Silk Road.[6] In the following centuries, a great cultural influx benefited China, embodied by the appearance in China of foreign art, new ideas and religions (especially Buddhism), and new lifestyles.[6] Artistic influences combined a multiplicity of cultures which had intermixed along the Silk Road, especially Hellenistic, Egyptian, Indian and Central Asian cultures, displaying a strong cosmopolitanism.[5][6]

Such mixed influences are especially visible in the earthenwares of Northern China in the 6th century, such as those of the Northern Qi (550-577) or the Northern Zhou (557-581).[5][6] In that period, high quality high-fired earthenware starts to appear, called the "jeweled type", which incorporates lotuses from Buddhist art, as well as elements of Sasanian designs such as pearl roundels, lion masks or musicians and dancers.[5] The best of these ceramics use bluish green, yellow or olive glazes.[5]

Early Islamic period

Direct contacts between the Muslim and Chinese worlds were marked by the Battle of Talas in 751 in Central Asia. Muslim communities are known to have been present in China as early as the 8th century CE, especially in commercial harbours such as Canton and Hangzhou.[3]

From the 9th century onwards, Islamic merchants started to import Chinese ceramics, which were at the core of the Indian Ocean luxury trade at that time.[2][3] These exotic objects were cherished in the Islamic world and also became an inspiration for local potters.[2][3]

Archaeological finds of Chinese pottery in the Middle East go back to the 8th century, starting with Chinese pottery of the Tang period (618-907).[1][7] Remains of Tang period (618-907) ceramics have been found in Samarra and Ctesiphon in present-day Iraq, as well as in Nishapur in present-day Iran.[6] These include porcelaneous white wares from Northern Chinese kilns, celadon-glazed stoneware originating in the Yue kilns of Northern Zhejiang, and the splashed stoneware of Changsha kilns in Hunan Province.[6][7]

Chinese pottery was the object of gift-making in Islamic lands: the Islamic writer Muhammad Ibn-al-Husain-Bahaki wrote in 1059 that Ali Ibn Isa, the governor of Khurasan, presented Harun al-Rashid, the Caliph, twenty pieces of Chinese imperial porcelain, the like of which had never been at a caliph's court before, in addition to 2,000 other pieces of porcelain".[1]

Yuan and Ming dynasties

By the time of the Mongol invasion of China a considerable export trade westwards to the Islamic world was established, and Islamic attempts to imitate Chinese porcelain in their own fritware bodies had begun in the 12th century. These were less successful than those of Korean pottery, but eventually were able to provide attractive local competition to Chinese imports.[8] Chinese production could adapt to the preferences of foreign markets; larger celadon dishes than the Chinese market wanted were favoured for serving princely banquets in the Middle East. Celadon wares were believed there to have the ability to detect poison, by sweating or breaking.[9] After about 1450 celadon wares fell out of fashion in China, and the continuing production, of lower quality, was for export.

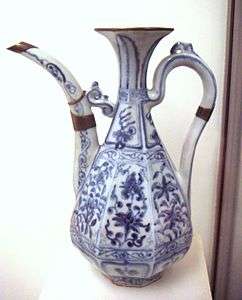

The Islamic market was apparently especially important in the early years of Chinese blue and white porcelain, which appears to have been mainly exported until the Ming; it was called "Muslim blue" by the Chinese. Again, large dishes were an export style, and the densely painted decoration of Yuan blue and white borrowed heavily from the arabesques and plant scrolls of Islamic decoration, probably mostly taking the style from metalwork examples, which also provided shapes for some vessels. This style of ornament was then confined to blue and white, and is not found in the red and white painted wares then preferred by the Chinese themselves. The cobalt blue that was used was itself imported from Persia, and the export trade in porcelain was handled by colonies of Muslim merchants in Quanzhou, convenient for the huge Jingdezhen potteries, and other ports to the south.[10]

The start of the Ming dynasty was quickly followed by a decree of 1368, forbidding trade with foreign countries. This was not entirely successful, and had to be repeated several times, and the giving of lavish imperial diplomatic gifts continued, concentrating on silk and porcelain (19,000 pieces of porcelain in 1383), but it severely set back the export trade. The policy was relaxed under the next emperor after 1403, but had by then greatly stimulated the production of pottery emulating Chinese styles in the Islamic world itself, which was by now reaching a high level of quality in several countries (high enough to fool contemporary Europeans in many cases).[11]

Often Islamic production imitated not the latest Chinese styles, but those of the late Yuan and early Ming.[12] In turn, Chinese potters began in the early 16th century to produce some items in overtly Islamic styles, including jumbled inscriptions in Arabic. These appear to have been made for the growing Chinese Muslim market, and probably those at court wishing to keep up with the Zhengde Emperor's (r. 1505-1521) flirtation with Islam.[13]

Evolution

Yue ware

Yue ware originated in the Yue kilns of Northern Zhejiang, in the site of Jiyuan near Shaoxing, called "Yuezhou" (越州) in ancient times.[6][14] Yue ware was first manufactured from the 2nd century CE, when it consisted in some very precise imitations of bronze vessels, many of which were found in tombs of the Nanjing region.[14] After this initial phase, Yue ware evolved progressively into true ceramic form, and became a true medium of artistic expression.[14][15] Production in Jiyuan stopped in the 6th century, but expanded to various areas of Zhejiang, especially around the shores of Shanglinhu in Yuyaoxian.[14][15]

Yue ware was highly valued, and was used as tribute for the imperial court in northern China in the 9th century.[15] Significantly, it was also used in China's most revered Famen Temple in Shaanxi Province.[15] Yue ware was exported to the Middle East early on, and shards of Yue ware have been excavated in Samarra, Iraq, in an early example of Chinese influences on Islamic pottery,[6] as well as to East Asia and South Asia as well as East Africa from the 8th to the 11th century.[15]

Sancai ware

Right image: Iraqi lobed dish inspired from Tang examples, 9-10th century. British Museum.

Tang period earthenware shards with low-fired polychrome three-color sancai glazes from the 9th century were exported to Middle-Eastern countries such as Iraq and Egypt, and have been excavated in Samarra in present-day Iraq and in Nishapur in present-day Iran.[6][16] These Chinese styles were soon adopted for local Middle-Eastern manufactures. Copies were made by Iraqi craftsmen as soon as the 9th century CE.[3][17]

In order to imitate Chinese Sancai, lead glazes were used on top of vessels coated with white slip and a colorless glaze. The coloured lead glazes were then splashed on the surface, where they spread and mixed, according to the slipware technique.[2]

Shapes were also imitated, such as the lobed dishes found in Chinese Tang ceramics and silverware which were reproduced in Iraq during the 9-10th century.[3]

Conversely, numerous Central Asian and Persian influences were at work in the designs of Chinese sancai wares: pictures of Central Asian mounted warriors, scenes representing Central Asian musicians, vases in the shape of Middle-Eastern ewers.

-

Iran three-color ceramic, 9-10th century.

-

Syrian three-color ceramic, 13th century.

-

Three-color glazed ceramics, Cyprus, 14th century.

White ware

Soon after the sancai period, Chinese white ware ceramics also found their way to the Islamic world,[7][16] and were immediately reproduced.[3] The Chinese white ware was actually porcelain, invented in the 9th century, and used kaolin and high-temperature firing,[2] but Islamic workshops were unable to duplicate its manufacture. Instead, they manufactured fine earthenware bowls with the desired shape, and covered them with a white glaze rendered opaque by the addition of tin, an early example of tin-glazing.[2][3][17] The Chinese shapes were also reproduced, seemingly to pass for China-made wares.[2]

In the 12th century, Islamic manufacturers further developed stone-paste techniques in order to obtain hard bodies approximating the hardness obtained by Chinese porcelain. This technique was used until the 18th century, when the Europeans discovered the Chinese technique for high-firing porcelain clays.[2][3]

Celadon ware

The Chinese fashion for greenware, or celadon, ware was also transmitted to the Islamic world, where it gave rise to productions using turquoise glazing and fish motifs identical to the ones used in China.[3]

Blue and white ware

Right image: Stone-paste dish with grape design, Iznik, Turkey, 1550-70. British Museum.

The technique of cobalt blue decorations seems to have been invented in the Middle East in the 9th century through decorative experimentation on white ware,[2] and the technique of blue-and-white ware was developed in China in the 14th century.[2][18] On some occasions, Chinese blue and white wares also incorporated Islamic designs, as in the case of some Mamluk brass works which were converted into blue and white Chinese porcelain designs.[3] Chinese blue and white ware then became extremely popular in the Middle East, where both Chinese and Islamic types coexisted.[2]

From the 13th century, Chinese pictorial designs, such as flying cranes, dragons and lotus flowers also started to appear in the ceramic productions of the Near East, especially in Syria and Egypt.[3]

Chinese porcelain of the 14th or 15th century was transmitted to the Middle East and the Near East, and especially to the Ottoman Empire either through gifts or through war booty. Chinese designs were extremely influential with the pottery manufacturers at Iznik, Turkey. The Ming "grape" design in particular was highly popular and was extensively reproduced under the Ottoman Empire.[3] The style of Persian pottery known as Kubachi ware also absorbed influence from China, imitating both celadons and Ming blue-and-white porcelain.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Studies in Chinese ceramics by Dekun Zheng, Cheng Te-K'Un p.90ff

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Medieval Islamic civilization: an encyclopedia by Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach p.143

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Notice of British Museum "Islamic Art Room" permanent exhibit.

- ↑ British Museum, Ancient China permanent exhibit

- 1 2 3 4 5 The arts of China by Michael Sullivan p.119ff

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Notice of the Metropolitan Museum of Art permanent exhibition.

- 1 2 3 Maritime silk road Qingxin Li p.68

- ↑ Vainker, Ch. 5, pp. 134, 140-141 especially

- ↑ Vainker, 136-137

- ↑ Vainker, 137-140; Clunas and Harrison-Hall, 86-95

- ↑ Vainker, 140-142

- ↑ Vainker, 140-141

- ↑ Vainker, 142-143

- 1 2 3 4 The arts of China by Michael Sullivan p.90ff

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chinese glazes: their origins, chemistry, and recreation Nigel Wood p.35ff

- 1 2 Chinese glazes: their origins, chemistry, and recreation Nigel Wood p.205ff

- 1 2 Islamic art by Barbara Brend p.41

- ↑ Porcelain. Columbia Encyclopedia

References

- Clunas, Craig and Harrison-Hall, Jessica, Ming: 50 years that changed China, 2014, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714124841

- Vainker, S.J., Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, 1991, British Museum Press, 9780714114705

Further reading

- Canby, Sheila R. (ed). Shah Abbas; The Remaking of Iran, 2009, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714124520

- Crowe, Yolande (2002). Persia and China: Safavid Blue and White Ceramics in the Victoria and Albert Museum 1501-1738. London: La Borie. ISBN 978-0953819614.

- Rawson, Jessica (1984). Chinese Ornament: The Lotus and the Dragon. London: British Museum Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0714114316.

- Wilkinson, Charles K. (1973). Nishapur: pottery of the early Islamic period. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870990764.

External links

- A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries