Chinatowns in the Americas

| Chinatown | |||||||

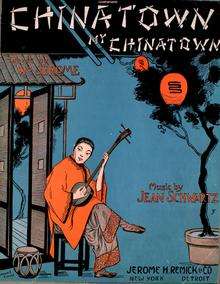

Cover of sheet music, published in 1910 | |||||||

| Chinese | 唐人街 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國城 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国城 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 華埠 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 华埠 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Chinatowns |

|---|

This article discusses Chinatowns in the Americas. The regions include: Canada, the United States and the Latin Americas.

Locations

Canada

Chinatowns in Canada generally exist in the large cities of Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, Winnipeg, Toronto, and Montreal, and existed in some smaller towns throughout the history of Canada. Prior to 1900, almost all Chinese were located in British Columbia, but have spread throughout Canada thereafter. From 1923 to 1967, immigration from China was suspended due to exclusion laws. In 1997, the handover of Hong Kong to China caused many from there to flee to Canada due to uncertainties. According to an article from the Globe and Mail, Canada had 25 Chinatowns total across the entire country between the 1930s to 1940s, some of which had become extinct.[1]

Vancouver's Chinatown is the largest in Canada.[2] Dating back to the late 19th century, the main focus of the older Chinatown is Pender Street and Main Street in downtown Vancouver, which is also, along with Victoria's Chinatown, one of the oldest surviving Chinatowns in North America. Vancouver has been the setting for a variety of modern Chinese Canadian culture and literature. Vancouver's Chinatown contains numerous galleries, shops, restaurants, and markets, in addition to the Chinese Cultural Centre and the Dr. Sun Yat Sen Classical Chinese Garden and park; the garden is the first and one of the largest Ming era-style Chinese gardens outside China. Although only one neighborhood is designated as Chinatown in modern Greater Vancouver, the high proportion of Chinese people living in the region (the highest in North America) has created many commercial and residential areas that while Chinese-dominated are not called "Chinatown". In Greater Vancouver that term refers only to the historic Chinatown in the city core. There is an abundance of Chinese- and Asian-themed malls in the region, with the highest concentration in the Golden Village district of Richmond.

Chinatown, Toronto is an ethnic enclave in Downtown Toronto, Ontario, Canada, with a high concentration of ethnic Chinese residents and businesses extending along Dundas Street West and Spadina Avenue. First developed in the late 19th century, it is as of 2012 one of the largest Chinatowns in North America and one of several major Chinese-Canadian communities in the Greater Toronto Area.

Additional Chinatowns exist in Calgary, Edmonton, Montreal, Ottawa, Victoria, and Winnipeg. Historical Chinatowns were in Nanaimo, New Westminster, Mission, Lillooet, Barkerville and Penticton, to name a few of many. Some towns that were majority Chinese for years, such as Stanley, Rock Creek and Richfield were not known as Chinatowns (Barkerville has a Chinatown area, though most Chinese lived outside it, and many non-Chinese lived in its Chinatown).

United States

Chinatowns in the United States of America have existed since the 1840s on the West Coast and the 1870s on the East Coast. The Chinese were one of the first Asian groups to arrive in large numbers. Circumstances caused by the Korean and Vietnam wars, the 1965 Immigration Act, in addition to the desire for skilled workers caused more immigration from China and the rest of Asia. As of the early 21st century the Chinese are the largest of the Asian immigrant groups; and have been so for most of the history of the United States. As other immigrants of other countries arrive, Chinatown, the oldest of the Asian ethnic enclaves has become a pattern for other Asian enclaves such as Japantown, Koreatown, and Little India.[3] The Manhattan Chinatown in New York City contains the largest Chinese population outside of Asia, while the Chinatown in San Francisco is one of the oldest in the country.

New York City

The New York metropolitan area contains the largest ethnic Chinese population outside of Asia,[4][5] enumerating 779,269 individuals as of 2013,[6] including at least 12 Chinatowns - six[7] (or nine, including the emerging Chinatowns in Corona and Whitestone, Queens,[8] and East Harlem, Manhattan) in New York City proper, and one each in Nassau County, Long Island; Edison, New Jersey;[8] and Parsippany-Troy Hills, New Jersey, not to mention fledgling ethnic Chinese enclaves emerging throughout the New York City metropolitan area. Chinese Americans, as a whole, have had a (relatively) long tenure in New York City.

The first Chinese immigrants came to Lower Manhattan around 1870, looking for the "golden" opportunities America had to offer.[9] By 1880, the enclave around Five Points was estimated to have from 200 to as many as 1,100 members.[9] However, the Chinese Exclusion Act, which went into effect in 1882, caused an abrupt decline in the number of Chinese who immigrated to New York and the rest of the United States.[9] Later, in 1943, the Chinese were given a small quota, and the community's population gradually increased until 1968, when the quota was lifted and the Chinese American population skyrocketed.[9] In the past few years, the Cantonese dialect that has dominated Chinatown for decades is being rapidly swept aside by Mandarin Chinese, the national language of China and the lingua franca of most of the latest Chinese immigrants.[10]

San Francisco

A Pacific port city, San Francisco has the oldest and longest continuous running Chinatown in the Western Hemisphere.[11][12][13] [12] It originated circa 1848 and served as a gateway for incoming immigrants who arrived during the California gold rush and the construction of the North American transcontinental railroads. Chinatown was later reconceptualized as a tourist attraction in the 1910s.

San Francisco's Chinatown was nearly, but not completely destroyed by the 1906 earthquake, but many of its inhabitants did not relocate elsewhere. Looming large were proposals by real estate speculators and politicians to expand the Financial District's influence into the area, by displacing the Chinese community to the southern part of the city. In response, many of Chinatown's residents and landlords defiantly stayed behind to stake their neighborhood's claim, sleeping out in the open and in makeshift tents. Numerous businesses and housing based in brick buildings survived with moderate damage and continued functioning, if only in a limited capacity. In just two years after the earthquake, the landmark Sing Fat and Sing Chong buildings were completed as a statement of the Chinese community's resolve to remain in the area. As a result of this action, Chinatown remains the longest, continuously occupied Chinese community outside of Asia.[11][12][13]

Still a community of predominantly Taishanese-speaking inhabitants, San Francisco's Chinatown became one of the most important Chinese centers in the United States.[14][15]

Latin America

Chinatowns in Latin America (Spanish: barrios chinos, singular barrio chino / Portuguese: bairros chineses, singular bairro chinês) developed with the rise of Chinese immigration in the 19th century to various countries in Latin America as contract laborers (i.e., indentured servants) in agricultural and fishing industries. Most came from Guangdong Province. Since the 1970s, the new arrivals have typically hailed from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Latin American Chinatowns may include the descendants of original migrants — often of mixed Chinese and Latino parentage — and more recent immigrants from East Asia. Most Asian Latin Americans are of Cantonese and Hakka origin. Estimates widely vary on the number of Chinese Descendants in Latin America but it is at least 1.4 million and likely much greater than this. The oldest Chinatown in the Latin America is in Mexico City which dates back to at least the early 17th century.[16] Two notable Chinatowns exist in Buenos Aires, Argentina and Lima, Peru.

| Latin American Chinatowns | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

References

- ↑ "Quebec City's Chinatown - gone but not forgotten". Hogtown Front. June 18, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2014. which in turn references Ingrid Peritz (June 17, 2006). "Chinatown is gone, gone to heaven". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ "Chinatown Vancouver Online". Vancouverchinatown.ca. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ↑ David Johnson. "Chinatowns and Other Asian-American Enclaves". Infoplease. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ↑ Vivian Yee (February 22, 2015). "Indictment of New York Officer Divides Chinese-Americans". The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Chinese New Year 2012 in Flushing". QueensBuzz.com. 25 January 2012. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑ "ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates New York-Newark-Bridgeport, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-11-10.

- ↑ Kirk Semple (June 23, 2011). "Asian New Yorkers Seek Power to Match Numbers". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

- 1 2 Lawrence A. McGlinn (2002). "Beyond Chinatown: Dual Immigration and the Chinese Population of Metropolitan New York City, 2000" (PDF). Middle States Geographer. 35 (1153): 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

- 1 2 3 4 Waxman, Sarah. "The History of New York's Chinatown". ny.com. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

- ↑ Semple, Kirk (October 21, 2009). "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- 1 2 Bacon, Daniel: Walking the Barbary Coast Trail 2nd ed., page 50, Quicksilver Press, 1997

- 1 2 3 Richards, Rand: Historic San Francisco, 2nd Ed., page 198, Heritage House Publishers, 2007

- 1 2 Morris, Charles: San Francisco Calamity by Earthquake and Fire, pp. 151–152, University of Illinois Press, 2002

- ↑ "USA". Chinatownology.com. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ↑ "Chinatown San Francisco Pictures and History". Inetours.com. 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ↑ Mann, Charles C. (2012). 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 416. ISBN 978-0-307-27824-1. Retrieved 12 October 2012.