Chichibabin pyridine synthesis

| Chichibabin pyridine synthesis | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Aleksei Chichibabin |

| Reaction type | Ring forming reaction |

| Identifiers | |

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000526 |

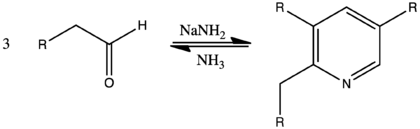

The Chichibabin pyridine synthesis (/ˈtʃitʃiˌbeɪbin/ CHEE-chee-BAY-been) is a method for synthesizing pyridine rings. In its general form, the reaction can be described as a condensation reaction of aldehydes, ketones, α,β-Unsaturated carbonyl compounds, or any combination of the above, in ammonia or ammonia derivatives.[1] It was reported by Aleksei Chichibabin in 1924.[2] The following is the overall form of the general reaction:

Reaction mechanism

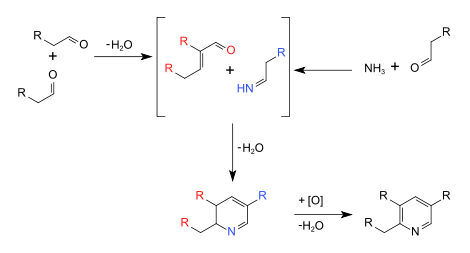

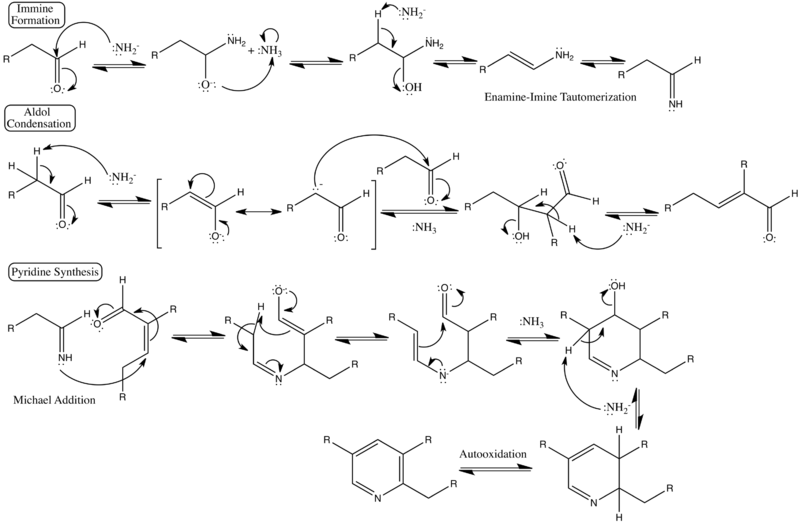

The elementary contributing steps of the reaction mechanism can be classified as more familiar name reactions, including an imine synthesis, a base-catalyzed aldol condensation, and initiating the ring-synthesis step, a Michael reaction.

Fundamental reaction steps

Detailed reaction mechanism

Showing detailed curved-arrow electron pushing steps, formal charges, and categorized steps of the reaction.[3][4]

Synthetic applications

Alkyl-substituted pyridines show widespread uses among multiple fields of applied chemistry, including the polymer and pharmaceutical industries. For example, 2-methylpyridine, 4-methylpyridine and 2-ethyl-5-methylpyridine exhibit widespread use in syntheses of latexes, ion-exchange matrixes, and photography materials.[5]

Limitations

One of the chief limitations of practical application of the traditional Chichibabin pyridine synthesis is its consistently low product yield. With the exception of two experimental runs, Chichibabin himself was unable to obtain product yields in excess of 20% across a variety of reactants, solvents, and other experimental conditions. This, in concert with the high prevalence of byproducts, which would require a multitude of purification steps to isolate pure pyridine product, render unaltered forms of Chichibabin's method unsuitable for applied chemistry.[1][2]

The high proportion of byproducts and low yield are explained by the easily reversible nature of the aldol condensation, and carbonyl chemistry in general.[1] For instance, the following side-reactions could lead to byproduct formation:

Imine formation steps:

1.Nucleophilic attack of ammonia at the β-, rather than α-carbon will prevent enamine/imine formation

2.Nucleophilic attack of ammonia on the enamine or imine

Aldol condensation step

3.(In the case of asymmetric ketones), abstraction of the non-preferred β-Hydrogen

4.Enolate ion attack of the enamine or imine carbon

5.Enolate ion attack of an unintended aldehyde- or keto-carbonyl

Pyridine synthesis step

6. Imine attack of carbonyl-, rather than γ-carbon

7. Imine attack at an enamine or imine carbon

In the case of simple aldehydes and, and particularly in the case of α,β-Unsaturated carbonyl compounds, polymerization of starting materials can occur frequently and is shown to significantly decrease yields.[1]

Ways to overcome limitations

1. Protection of the carbonyl increases product yields[1]

2. Use of paraldehyde as a source of gradually available ethanal[1]

3. Large (>3x catalytic) excess of aqueous ammonia, with catalytic amounts of ammonium acetate[1][4]

4. Conducting the reaction in the gas phase and passing-over a number of catalysts including aluminium(III) oxide (yield 65% at 600 K),[5] zeolite (yield 98.9% at 500 K),[6] and many others.

5. Increased pressures and temperature[1][4]

In vivo evidence of this mechanism

In vivo, deamination of the α-amino group of amino acids produces small amounts of ammonia. Researchers found that protein-incorporated allysine, (deaminated lysine) from bovine ligamentum nuchae elastin fibers appeared to be pyridine crosslinked. The structures of these cross-linked amino acids had 3,4,5- and 2,3,5-trisubstituted pyridine skeletons, specifically pyridinated desmosine (DESP) and pyridinated isodesmosine (IDP).[7]

Extrapolating from an in-vitro elastin model under physiological conditions, the researchers found that the ratios of IDP to DESP corresponded extremely closely with values based on both a calculation of a theoretical Chichibabin pyridine synthesis of 3 mol allysine and 1 mol ammonia, and reported ratios of 2,3,5- to 3,4,5-trisubstituted pyridine ratios of a Chichibabin pyridine synthesis involving phenylacetaldehyde.[8] They concluded with relative certainty that the pyridine cross-links found in elastin were, in fact, due to an in-vivo Chichibabin pyridine synthesis of ammonia and allysine.[7]

See also

- Chichibabin reaction

- Gattermann–Skita synthesis

- Hantzsch pyridine synthesis

- Ciamician–Dennstedt rearrangement

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Frank, R. L.; Seven, R. P. (1949). "Pyridines. IV. A Study of the Chichibabin Synthesis". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 71 (8): 2629–35. doi:10.1021/ja01176a008.

- 1 2 Tschitschibabin, A. E. (1924). "Über Kondensation der Aldehyde mit Ammoniak zu Pyridinbasen". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 107 (1–4): 122–8. doi:10.1002/prac.19241070110.

- ↑ Li, J. J. (2009). "Chichibabin pyridine synthesis". Name Reactions. pp. 107–9. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01053-8_51. ISBN 3-540-40203-9.

- 1 2 3 Weiss, M. (1952). "Acetic Acid—Ammonium Acetate Reactions. An Improved Chichibabin Pyridine Synthesis". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 74 (1): 200–2. doi:10.1021/ja01121a051.

- 1 2 Sagitullin, R. S.; Shkil, G. P.; Nosonova, I. I.; Ferber, A. A. (1996). "Synthesis of pyridine bases by the Chichibabin method (review)". Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds. 32 (2): 127–40. doi:10.1007/BF01165434.

- ↑ Krishna Mohan, K. V. V.; Reddy, K. S. K.; Narender, N.; Kulkarni, S. J. (2008). "Zeolite Catalysed Synthesis of 5-Ethyl-2-methylpyridine under High Pressure". Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical. 298 (1–2): 99–102. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2008.10.010.

- 1 2 Umeda, H.; Takeuchi, M.; Suyam, K. (2001). "Two New Elastin Cross-links Having Pyridine Skeleton". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (16): 12579–87. doi:10.1074/jbc.M009744200. PMID 11278561.

- ↑ Farley, C. P.; Eliel, E. L. (1956). "Chichibabin Reactions with Phenylacetaldehyde. II". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 78 (14): 3477–84. doi:10.1021/ja01595a057.