Chase Court

| Chase Court | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Established | 1864 |

| Dissolved | 1873 |

| Country | United States |

| Location |

Old Senate Chamber Washington, D.C. |

| Number of positions | 8-10 |

The Chase Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1864 to 1873, when Salmon P. Chase served as the sixth Chief Justice of the United States. Chase succeeded Roger Taney as Chief Justice after the latter's death. Chase served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Morrison Waite was nominated and confirmed as Chase's successor. The Chase Court presided over the end of the Civil War and much of the Reconstruction Era. During the Chase Court, Congress passed the Habeas Corpus Act 1867, giving the court the ability to issue writs of habeas corpus for defendants tried by state courts. The Chase Court interpreted the Fourteenth Amendent for the first time, and its narrow reading of the Amendment would be adopted by subsequent courts.[1]

Membership

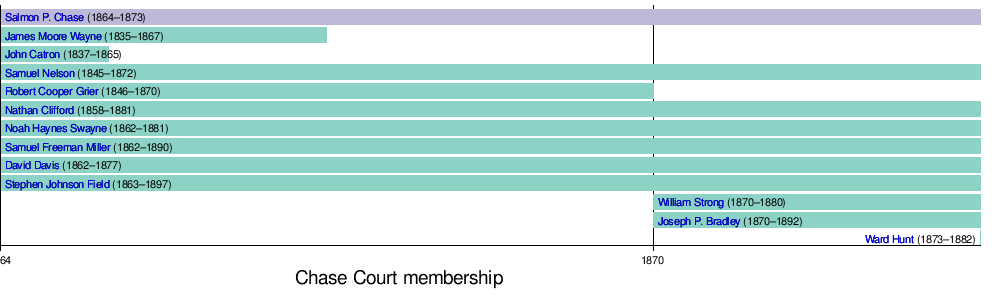

The Chase Court began when President Abraham Lincoln appointed Samuel Chase to replace Chief Justice Roger Taney, who died in 1864. The Chase Court commenced with Chase and nine Associate Justices: James Moore Wayne, John Catron, Samuel Nelson, Robert Cooper Grier, Nathan Clifford, Noah Haynes Swayne, Samuel Freeman Miller, David Davis, Stephen Johnson Field.

During Chase's tenure, Congress passed two laws setting the size of the Supreme Court, partly to prevent President Andrew Johnson from appointing Supreme Court justices. The Judicial Circuits Act of 1866 provided for the elimination of three seats (to take effect as sitting justices left the court), which would reduce the size of the court from ten justices to seven. Catron died in 1865, and he had not been replaced when the Judicial Circuits Act was passed, so his seat was abolished upon passage of the act. Wayne died in 1867, leading to the abolition of his seat. However, Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1869, setting the size of the court at nine justices and creating a new seat. In 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed William Strong to replace Grier, and Joseph P. Bradley to fill the newly-created seat. Bradley was nominated after the Senate rejected Grant's nomination of Ebenezer R. Hoar; the Senate had also confirmed Edwin Stanton's nomination for the seat, but Stanton died before taking office. Nelson retired in 1872, and Grant appointed Ward Hunt to succeed him.

Chief Justice Associate Justice

Rulings of the Court

Notable rulings of the Chase Court include:

- Ex parte Milligan (1866): In an opinion written by Justice Davis, the court ruled that trials by military tribunal are constitutional only when the civil courts are not functioning, and there is no power left but the military. The case arose from an 1864 military tribunal in Indiana that tried several Union dissenters.

- Mississippi v. Johnson (1867): In an opinion written by Chief Justice Chase, the court rejected a Mississippi lawsuit seeking to force President Andrew Johnson to enforce Reconstruction laws. The court held that Johnson’s decision to enforce such laws was discretionary.

- Crandall v. Nevada (1868): In an opinion written by Justice Miller, the court struck down a Nevada statute that imposed a $1 tax on people leaving the state. The court held that the right to travel is a fundamental right that cannot be impeded by states.

- Georgia v. Stanton (1868): In an opinion written by Justice Nelson, the court refused to intervene in the enforcement of the Reconstruction Acts, holding that the case constituted a non-justiciable political question.

- Texas v. White (1869): In an opinion written by Chief Justice Chase, the court held that the Constitution does permits states to legally secede from the Union. The decision held that all acts of Confederate secession were legally null.

- Legal Tender Cases (1871): In a series of opinions, the court upheld the government's ability to print paper money under the Legal Tender Act.

- The Slaughter-House Cases (1873): In a 5-4 decision written by Justice Miller, the court held that the Fourteenth Amendment does not affect a state’s police power. The decision would be largely overruled by numerous Supreme Court decisions that incorporated the Bill of Rights to apply to state governments.

References

- ↑ Lurie, Jonathan (2004). The Chase Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. pp. 87–89. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

.jpg)