Chambered long barrow

Chambered long barrows, also known as megalithic long barrows or chambered tombs, were a style of monument constructed across Western Europe in the fifth and fourth millennia BCE, during the Early Neolithic period. Typically constructed from earth and stone, they represent the oldest widespread tradition of stone construction in the world.

The long barrows consist of an earthen tumulus, or "barrow", with a stone chamber in one end. These monuments often contained human remains interned within their chambers, and as a result are often interpreted as tombs, although there are some examples where this appears not to have happened. Across Northern Europe, and overlapping with the chambered long barrows in some regions, were unchambered long barrows; the relationship between the two remains an issue of debate but may have been more to do with the availability of local materials however than any cultural differences.

The earliest examples developed in Iberia and western France during the mid-fifth millennium BCE. The tradition then spread northwards, into the British Isles and then the Low Countries and Southern Scandinavia. Each area developed its own regional variations on the chambered long barrow tradition, often exhibiting their own architectural innovations. The purpose and meaning of such barrows remains an issue of debate among archaeologists. One argument is that they are religious sites, perhaps erected as part of a system of ancestor veneration or as a religion spread by missionaries or settlers. An alternative explanation views them primarily in economic terms, as territorial markers delineating the areas controlled by different communities as they transitioned toward farming.

Around 40,000 chambered long barrows survive today. Many have been excavated by archaeologists, from whom our knowledge about them derives.

Terminology

Given their dispersal across Western Europe, chambered long barrows have been given different names in the various different languages of this region.[1] One of those to have achieved international usage has been "dolmen", a Breton word meaning "table-stone".[1] The term "barrow" is a southern English dialect word for an earthen tumulus, and was adopted as a scholarly term for such monuments by the 17th century English antiquarian John Aubrey.[2] Synonyms found in other parts of Britain included low in Cheshire, Staffordshire, and Derbyshire, tump in Gloucestershire and Hereford, howe in Northern England and Scotland, and cairn in Scotland.[3]

The term "chambered tombs" came to be applied to these monuments by archaeologists in the early twentieth century; the use of the term "tomb" acknowledged that many of these barrows contained human remains interned in them.[1] However, not all of these monuments did contain human remains, leading the historian Ronald Hutton to suggested that the term "tomb-shrines" should be applied to them instead.[4] Roy and Lesley Adkins referred to these monuments as "megalithic long barrows".[5]

Description

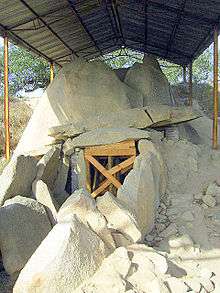

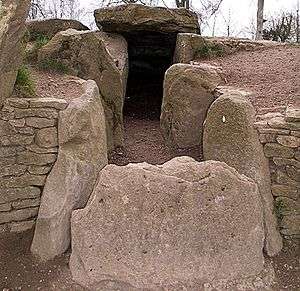

The basic structure of a chambered long barrow was that of a rectangular or oval earthen tumulus, into one end of which was placed a chamber created by large stone boulders, or "megaliths".[1] In using stone, these long barrows are distinguished from the earthen long barrows which were also created in the Early Neolithic.[6] Many were altered and restyles over their long period of use.[7] It is possible that some chambers never had earthen mounds added to them.[3]

Hutton suggested that it is this tradition which "defines the Early Neolithic of Western Europe" like no other.[1] For the archaeologist Caroline Malone, the long barrows are "some of the most impressive and aesthetically distinctive constructions of prehistoric Britain".[8] Her fellow archaeologist Frances Lynch stated that these long barrows "can still inspire awe, wonder and curiosity even in modern populations familiar with Gothic cathedrals and towering skyscrapers."[9] They were built all along the seaboard of Western Europe during the Early Neolithic, from Southeastern Spain up to Southern Sweden, taking in most of the British Isles.[1]

Although there are stone buildings—like Göbekli Tepe in modern Turkey—which predate them, the chambered long barrows constitute humanity's first widespread tradition of construction using stone.[4] The archaeologist Frances Lynch has described them as "the oldest built structures in Europe" to survive.[9] In most cases, local stone was used where it was available.[7] In some locations, where stone was not available, timber was used as a replacement.[1] Ascertaining at what date a chambered long barrow was constructed is difficult for archaeologists as a result of the various modifications that were made to the monument during the Early Neolithic.[10] Similarly, both modifications and later damage can make it difficult to determine the nature of the original long barrow design.[11]

The style of the chamber falls into two categories. One form, known as grottes sepulchrales artificielles in French archaeology, are dug into the earth.[12] The second form, which is more widespread, are known as cryptes dolmeniques in French archaeology and involved the chamber being erected above ground.[12] Many chambered long barrows contained side chambers within them, often producing a cruciform shape.[13] Others had no such side alcoves; these are known as undifferentiated tombs.[13]

Enviro-archaeological studies have demonstrated that many of the chambered long barrows were erected in wooded landscapes.[14] In Britain, these chambered long barrows are typically located on prominent hills and slopes,[15] in particular being located above rivers and inlets and overlooking valleys.[16] In Britain, chambered long barrows were also often constructed near to causewayed enclosures, a form of earthen monument.[7]

Human remains

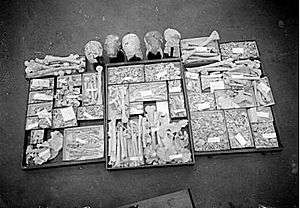

Many of the chambered long barrows contain human remains.[1] For this reason, archaeologists like Malone have referred to them as "houses of the dead".[8] The archaeologists David Lewis-Williams and David Peace however noted that these long barrows were more than tombs, also being "religious and social foci", suggesting that they were places where the dead were visited by the living and where people maintained relationships with the deceased.[17] However, there are some examples which appear to have never had any human remains placed into them.[18]

In some cases, the bones being deposited in the chamber may have been old at the time of the deposition.[10] In other instances, they may have been placed into the chamber long after the long barrow was built.[10] Large sections of the Early Neolithic population were not buried in them, although how their bodily remains are dealt with is not clear.[8] It is possible that they were left in the open air.[8]

In some chambers, it is apparent that human remains were arranged and organised according to the type of bone or the age and sex of the individual that they came from, factors which determined the location in the chamber that they were deposited.[10] In the Severn-Cotswold tomb group in southwestern England, cattle bones were commonly found within the chambers, where they had often been treated in a manner akin to the human remains.[19]

Sometimes human remains were deposited in the chambers over many centuries.[10] For instance, at West Kennet Long Barrow in Oxfordshire, Southern England, the earliest depositions of human remains were radiocarbon dated to the early-to-mid fourth millennium BCE, while a later deposition of human remains was found to belong to the Beaker culture, thus indicating a date in the final centuries of the third millennium BCE; this meant that human remains had been placed into the chamber intermittently over a period of 1500 years.[10] This indicates that some chambered long barrows remained in sporadic use until the Late Neolithic.[20]

Origins

The exact origins of the chambered long barrow tradition is unknown.[4] It has not been possible to identify which was the very first, primordial example built before the others.[4] However, dating evidence indicates that the earliest chambered long barrows were those built in Iberia and Western France; these have provided dates in the mid-fifth millennium BCE, and may possibly be older.[4] The tradition had appeared in Britain in the first half of the fourth millennium BCE, either soon after farming or in some cases perhaps just before it.[4] It later spread into northern areas, for instance arriving in the Netherlands in the second half of the fourth millennium BCE.[4] This indicates that the tradition spread from south to north, along the Atlantic coastline.[4]

The source of inspiration for the design of the chambered long barrows remains unclear.[4] Suggestions that have proved popular among archaeologists is that they were inspired either by natural rock formations or by the shape of wooden houses.[21] It has been suggested that their design was based on the wooden long houses found in central Europe during the Early Neolithic, however there is a gap of seven centuries between the last known long houses and the first known chambered long barrows.[22]

Meaning and purpose

Among archaeologists, there is no agreed upon explanation for the original meaning and purpose of chambered long barrows.[22]

Religious sites

According to one possible explanation, the chambered long barrows served as markers of place that were connected to Early Neolithic ideas about cosmology and spirituality, and accordingly were centres of ritual activity mediated by the dead.[23] The inclusion of human remains has been used to argue that these long barrows were involved in a form of ancestor veneration.[23] Malone suggested that the prominence of these barrows suggested that ancestors were deemed far more important to Early Neolithic people than their Mesolithic forebears.[8] In the early twentieth century, this interpretation of the long barrows as religious sites was often connected to the idea that they were the holy sites of a new religion which had been spread by either settlers or missionaries; this explanation has been less popular with archaeologists since the 1970s.[22]

Adopting an approach based in cognitive archaeology, Lewis-Williams and Pearce argued that the chambered long barrows "reflected and at the same time constituted... a culturally specific expression of the neurologically generated tiered cosmos", a cosmos mediated by a system of symbols.[24] They suggested that the entrances to the chambers were viewed as transitional zones in which sacrificial rituals could take place, and that they were possibly also spaces for the transformation of the dead using fire.[19]

Territorial markers

A second explanation is that these chambered long barrows were intrinsically connected to the transition to farming, representing a new way of looking at the land. In this interpretation, the chambered long barrows served as territorial markers, dividing up the land, signifying that it was occupied and controlled by a particular community, and thus warning away rival groups.[22] In defending this interpretation, Malone noted that each "tomb-territory" typically had access to a range of soils and landscape types in its vicinity, suggesting that it could have represented a viable territorial area for a particular community.[7] Also supporting this interpretation is the fact that the distribution of chambered long barrows on some Scottish islands shows patterns which closely mirror those of modern land divisions between farms and crofts.[7] This interpretation also draws ethnographic parallels from recorded communities around the world, who have also used monuments to demarcate territory.[23]

This idea became popular among archaeologists in the 1980s and 1990s, and — in downplaying religion while emphasising an economic explanation for these monuments — it was influenced by Marxist ideas then popular in the European archaeological establishment.[25] In the early twenty-first century it began to be challenged as evidence emerged that much of Early Neolithic Britain was forested and its inhabitants pastoralists rather than agriculturalists. Accordingly, communities in Britain would have been semi-nomadic, with little need for territorial demarcation or a clear message about ownership of the land.[23] Also, this explanation fails to explain why the chambered long barrows should be clustered in certain areas rather than being evenly distributed throughout the landscape.[23]

Subsequent history

Decline

Later in the Neolithic, burial practices tended to place greater emphasis on the individual, suggesting a growing social hierarchy and a move away from collective burial.[8] One of the latest chambered tombs to be erected was Bryn Celli Ddu in Anglesey, Wales, built long after they had ceased to produced across most of Western Europe. The conscious anachronism of the monument led excavators to suggest that its construction was part of a deliberate attempt by people to restore older religious practices that had been extinct elsewhere.[26]

Many of the chambered long barrows have not remained intact, having been damaged and broken up during the millennia.[3] In various cases, most of the chamber has been removed, leaving only the three-stone dolmen remaining.[11]

Antiquarian and archaeological investigation

The first serious study of chambered long barrows took place in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the mounds that covered chambers were removed by agriculture.[27] By the nineteenth century, antiquarians and archaeologists had come to recognise this style of monument as a form of tomb.[27] In the latter nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, archaeologists like V. Gordon Childe held to the cultural diffusionist view that such Western European monuments had been based on tombs originally produced in parts of the eastern Mediterranean region, suggesting that their ultimate origin was either in Egypt or in Crete.[28]

In 1950, the archaeologist Glyn Daniel stated that about a tenth of known chambered long barrows in Britain had been excavated,[29] while regional field studies helped to list them.[29] Few of the earlier excavations recorded or retained any human remains found in the chamber.[10] From the 1960s onward, archaeological research increasingly focused on examining regional groups of long barrows rather than the wider architectural tradition.[30]

Regional forms

Around 40,000 examples of chambered long barrows survive, and can be subdivided into clear regionalised traditions based on architectural differences.[1]

Lewis-Williams and Pearce opined that the emphasis on classification of these monuments into sub-types could be a self-defeating aim for archaeologists, as it distracted them from the task of explaining the meaning and purpose behind them.[13]

They are concentrated in southern Britain and parts of northern England.

Chambered long barrow sub-types include:

- Severn-Cotswold tombs

- Certain Passage graves

- The Medway tombs

See also

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hutton 2013, p. 40.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 Daniel 1950, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hutton 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ Adkins, Adkins & Leitch 2008, p. 46.

- ↑ Adkins, Adkins & Leitch 2008, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Malone 2001, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Malone 2001, p. 103.

- 1 2 Lynch 1997, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Malone 2001, p. 108.

- 1 2 Daniel 1950, p. 7.

- 1 2 Daniel 1950, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Lewis-Williams & Pearce 2005, p. 181.

- ↑ Malone 2001, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Malone 2001, p. 106.

- ↑ Malone 2001, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Lewis-Williams & Pearce 2005, p. 179.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, pp. 40–41.

- 1 2 Lewis-Williams & Pearce 2005, p. 182.

- ↑ Malone 2001, p. 112.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, pp. 41—42.

- 1 2 3 4 Hutton 2013, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hutton 2013, p. 43.

- ↑ Lewis-Williams & Pearce 2005, p. 171.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, pp. 42, 43.

- ↑ Lewis-Williams & Pearce 2005, p. 186.

- 1 2 Lynch 1997, p. 8.

- ↑ Lynch 1997, pp. 8–9.

- 1 2 Daniel 1950, p. 3.

- ↑ Lynch 1997, p. 9.

Bibliography

- Adkins, Roy; Adkins, Lesley; Leitch, Victoria (2008). The Handbook of British Archaeology. London: Constable.

- Daniel, Glynn E. (1950). The Prehistoric Chamber Tombs of England and Wales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutton, Ronald (2013). Pagan Britain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19771-6.

- Lewis-Williams, David; Pearce, David (2005). Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos and the Realm of the Gods. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500051382.

- Lynch, Frances (1997). Megalithic Tombs and Long Barrows in Britain. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications.

- Malone, Caroline (2001). Neolithic Britain and Ireland. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1442-9.

Further reading

- Bradley, Richard (1998). The Significance of Monuments: On the Shaping of Human Experience in Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15204-6.

- Darvill, Timothy (2004). Long Barrows of the Cotswolds and Surrounding Areas. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752429076.

- Dronfield, J. (1995). "Migraine, Light and Hallucinations: The Neurocognitive Basis of Irish Megalithic Art". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 14 (3): 261–75.

- Kinnes, Ian (1975). "Monumental Function in British Neolithic Burial Practices". World Archaeology. 7 (1): 16–29.

- Watson, Aaron (2001). "The Sounds of Transformation: Acoustics, Monuments and Ritual in the British Neolithic". In Neil Price. The Archaeology of Shamanism. Routledge. pp. 178–192.

- Watson, Aaron; Keating, David (1999). "Architecture and Sound: An Acoustic Analysis of Megalithic Monuments in Prehistoric Britain". Antiquity. 73 (280). pp. 325–336.