Canonical sundial

A canonical sundial indicates the canonical hours of formal ritualistic acts. Such sundials were used from the 7th to the 14th centuries by members of religious communities.

Description

A canonical sundial is a fairly small carving on the south wall of a medieval religious building. The canonical sundial's purpose is to indicate the canonical hours when members of the community must perform certain religious acts, not to give the time of day.

The dial is usually a semi-circle, divided into 4, 6, 8, or 12 equal sectors. At the center of the circle, a horizontal stylus, perpendicular to the wall, casts its shadow on the sectors, giving the 'canonical hour'. The original wooden styli have long since disappeared, leaving a circular hole.

The dials are called 'canonical' because they mark the canonical hours. By convention, when the shadow of the stylus falls on one of the dividing lines of a sector, the corresponding prayers must be said. There were no numerical indications on the dial.

The dials were usually placed near the priests' door on the south side of the church at eye level. In an abbey or large monastery the dials were usually carefully carved in the stone walls. In rural churches they were very often just scratched on the wall, and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish them from graffiti.

During the 6th and 7th centuries each congregation had its own specific rites, and the number of graduations on the early canonical sundials varies. From the 8th century onwards the Rule of Saint Benedict, used by Benedictine and Cistercian communities was generally adopted.

The eight celebrations are: Matins/Vigils, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline. Matins, Lauds and Compline usually occur during the night hours.

- Typical canonical sundials

St. Michael's church

St. Michael's church

Coningsby, Lincolnshire UK- St. Martin Fresney-le-Puceaux, Calvados France

- St. Pierre-du-Palais

Charente-Maritime France - St Peter's church

Marsh Baldon, Oxfordshire UK

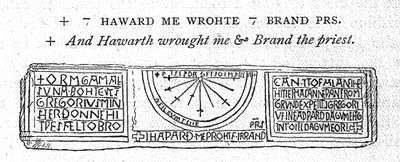

The Bewcastle Cross (7th century), Nendrum Monastery (9th century) and Kirkdale (11th century) dials are well-known examples of the canonical sundial. The Bewcastle Cross is the oldest known canonical sundial in England, carved on a Celtic cross in the church graveyard, and the Nendrum Monastery sundial gives the name of the sculptor and the priest.

By the 13th century, some canonical sundials, like the one at Strasbourg cathedral had become independent sculptures, and were not carved on the wall.

- Elaborate canonical sundials

The four sides of Bewcastle cross

The four sides of Bewcastle cross Celtic cross

Celtic cross

Bewcastle Cumbria, UK Kirkdale canonical sundial circa 1065

Kirkdale canonical sundial circa 1065 St. Gregory's Minster, Kikdale, Yorkshire, UK

St. Gregory's Minster, Kikdale, Yorkshire, UK Nendrum Monastery, North Ireland

Nendrum Monastery, North Ireland Cathedral circa 1240

Cathedral circa 1240

Strasbourg France

Towards the end of the 7th century, under the influence of the Venerable Bede (born in 632), and with the missionary activities of English, Irish and Scottish monks, the use of canonical sundials were generalized throughout Europe.

From the 14th century onwards, the cathedrals and large churches began to use clocks, and the canonical sundials lost their utility, except in small rural churches. The dials remained in use until the 16th century.

There are more than 3,000 canonical sundials in England[1][2] and at least 1,500 in France,[3] mainly in Normandy, Touraine, Charente and in monasteries along the routes to Saintiago de Compostella in northwestern Spain.

History

There are two main themes: how and why a sundial was adapted for liturgical use in England and where the canonical dial originates from.

Monastic use

In 7th century Europe, the various monastic communities were concerned about the organization of the time devoted to prayers, and about standardizing the rhythm of religious offices.[Notes 1] In the first half of the 6th century, Saint Benedict established a well-structured religious community under the authority of a spiritual father, the Abbot, who organized the three principal activities of the monks: the divine office (Opus Dei, or work of God), the reading of the Holy Scriptures or other spiritual authors (lectic divine) and manual labor. As in all monastic traditions, prayers occupied a central place. The different offices, based on the Rule of Saint Benedict are: eight canonical hours, separated by intervals of sleep, reading and labour, were reserved for divine offices.[Notes 2]

It is these moments for prayer that fix the canonical hours:

- Lauds, at Dawn (before sunrise), 4 bell chimes;

- Prime, the first 'hour' of the day, (the shadow is on the horizontal line of the dial), 3 bell chimes;

- Terce, the third 'hour' of the day, (the shadow is at 45°), 2 bell chimes;

- Sext, the sixth 'hour' of the day (mid-day), (the shadow is verical), 1 bell chime;

- None, the ninth 'hour' of the day, (the shadow is at 45°), 2 bell chimes;

- Vespers, the twelfth 'hour' of the day, the shadow is on the horizontal line of the dial), 3 bell chimes;

- Compline, after sunset, 4 bell chimes;

- Vigils, at mid-night.

A canonical sundial gives canonical hours, defined by the ecclesiastical liturgy, and has no direct link with civil hours. The canonical hours depend upon the geographical location and change with natural seasonal variations.

The backbones of the canonical sundial are the five day-time prayer 'hours', but, for community reasons, a dial can have other lines. In Saint Benedict's rule, it is clearly stated that each community is free to adapt its times for prayer as a function of local imperatives. This gives the possibility of creating further lines and sectors. To avoid confusion, the lines corresponding to prayers are longer than the others, or are marked with a cross. The majority of dials have these supplementary lines (between 6 and 12).

The interpretation of these extra lines, if one does not have any information about how the particular community functioned, is pure speculation.

Dials often have holes along the circumference of the semi-circle. T.W. Cole has suggested that these holes were not meant for extra styli, because they are usually quite shallow, but, given the fact that the churches were often painted with a white chalk or lime wash, the little holes were easily detected underneath the fresh coat of paint and a simple gouging out reconstructed the canonical sundial.[4]

The origin of the canonical sundial

The oldest known canonical sundial in England is on a Celtic cross in the graveyard of St. Cuthbert's church, Bewcastle, Cumbria, dating from the late 7th century. The cross is carved with the usual Celtic decoration, and in the middle of the south face there is a carved semi-circular sundial with twelve sectors. No earlier sundial like this, either in stone or drawn in a manuscript, is known in England.

It was just after the erection of this cross that canonical sundials started being used, first in England and then spreading over continental Europe, but usually with a much lower artistic quality. Since there is no evidence of an earlier use of such sundials and it is unlikely that the Bewcastle example was created independently in a flash of inspiration, one must suppose that it or the idea was imported from elsewhere.

Rev. T.W. Cole[5] has suggested a plausible explanation which is corroborated by Dr. David Thomson.[6]

The cross is probably the work of sculptors brought in by Benedict Biscop in the 670's to expand Monkwearmouth–Jarrow Abbey, one of the leading cultural centres in Northumbria. Biscop, a Benedictine Abbot, made several trips to Rome and returned to England with books, religious relics and Syrian sculptors who had fled the persecutions of Christians during the Islamic invasion of Syria and Egypt. The cross itself has several similarities with Syrian and Egyptian art. There are similarities to certain 5th century reliefs in the Cairo museum and the relief on the cross of a man with a falcon (assumed to be St. John the Evangelist and his eagle) is very similar to a Syrian model of St. John with an oil-lamp. The sundial on the south face is almost identical to an ancient Egyptian sundial, which was still used in Palestine in the 7th century.

The time system associated with this type of sundial is the same as that used in Palestine at the beginning of the Christian era. This system is easy to reconstruct because the authors of the Gospels were quite precise about noting the times of day.

We know that there were 12 'hours' in a day (John, chap XI, v 9) ; that the 'hours' were counted from sunrise to sunset (Matt. chap. XX, v. 1 - 12). Particular mention was made of the 3rd, 6th and 9th 'hours' (Matt. ch. XX, v 3 et 5), the 10th (John, ch. I v. 39), the 11th (Matt. ch XX, v. 6) and the 12th (John ch. XI, v. 9). Moreover, the 'hour' was a time duration, for we have references to 'one hour' (Luke, ch. XXII, v. 59), '2 hours' (Acts, ch. XIX, v. 34), '3 hours' (Acts, ch. XXII, v. 59) and 'half an hour' (Rev. ch. VIII, v. 1).

The 'hours' corresponding to events that occurred during the crucifixion are in Saint Benedict's canonical hours and the only available instrument at the time, capable of showing these 'hours', was the Egyptian sundial, of which the Bewcastle cross version is a copy.

Other names

In historical literature concerning sundials, canonical dials are also known as mass dials, scratch dials, or tide dials.

These names, whilst evocative, are inappropriate when one refers to the totality of canonical sundials :

- Mass dial. A canonical sundial indicates the canonical hours, which are periods of prayers, not the times for 'Mass', which necessarily involves the Eucharist celebration.

- Scratch dial. It is true that very many canonical sundials look like scratches on a church wall, but many are carefully carved and it would be insulting to refer to then all as 'scratched'.

- Tide dial is etymologically correct. But 'Tide', meaning a moment of time, is an obsolete word and survives only as 'eventide', 'noontide', 'Yuletide' etc. and, in any case, the 'Tide' does not specifically refer to ecclesiastical times.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canonical sundials. |

Notes

- ↑ Charlemagne, with an eye on pacifying and unifying his territory in order to make an empire, imposed that all the different churches, which had different Christian rites, to celebrate the liturgy of the Church of Rome. The canon law of Rome replaced all the different local canons. His son Louis the Pious finished his programme by imposing the Rule of Saint Benedict, for the organisation of religious communities, throughout the Holy Roman Empire.

- ↑ The obligation for monks to pray at specified moments of the day comes from the Jewish tradition of reciting prayers at fixed times. The apostles, Peter and John, went to the Temple for the after-noon prayers (Acts ch. 3, v. 1) and Psalm 119 mentions the seven daily prayers. Following the apostles' example, Christian communities adopted the tradition, but with many local variations. Saint Benedict's Rule was the beginning of a harmonization that would be imposed on all the European monastic communities by Charlemagne and his son.

References

- ↑ Canonical sundials inventory U.K.

- ↑ Cole (1935), pages 10-16, gives a list of 1300 English churches.

- ↑ Denis Schneider, Les cadrans canoniaux, L'Astronomie, 76 (2014), pp. 58-61.

- ↑ T.W. Cole (1935), page 2-3.

- ↑ T.W. Cole (1938), pages 148-150

- ↑ Officiel Bewcastle web-site

External links

- Canonical sundials in Touraine, France

- Canonical sundials in Tarn, France

- Medieval mass dials decoded by Peter T.J. Rumley

- Canonical sundials en Sussex, U.K.

Bibliography

- T.W. Cole (1935), Origin and Use of Church Scratch-Dials, Ed. Murray & Co., London ISBN 978-0953897711

- T.W. Cole (1938) Medieval church sundials, Suffolk Institute of Archéology & History, vol 23, Pt 2, pp. 148-154.

- Alan Cook (2012), Time Addendum to Mass Dials on Yorkshire Churches, Ed. British Sundial Society, 2012, Collection : BSS Monograph ISBN 978-0955887253.

- Arthur Robert Green (1926), Incised Dials or Mass-Clocks, Ed. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London.

- Abbot Ethelbert Horne (1929), Scratch Dials Their Description and History, ed. Simpkin Marshall, London.

- H. Michell Whitley (1919), Primitive Sundials on West Sussex churches,Sussex Archeological Collections, vol 60,1919, pp. 126-140.