Californio

| ||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10,000 in 1845, estimated.[1]) | ||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||

| Castilian Spanish; | ||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Roman Catholic | ||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||

| Castilians, Andalusians, other Spanish peoples | ||||||||||

Californio (historical and regional Spanish for "Californian") is a Spanish term for a descendant of a person of Castillian or other Spanish ancestry who was born in what is now the U.S. state of California before it was annexed by the United States when the region was still under Spanish and later Mexican control. The Californio era was from the first Spanish presence established by the Portolá expedition in 1769 until the region's cession to the United States of America in 1848. Persons of similar characteristics but born on the Baja California peninsula during the same time period may also be considered Californios, since that area (now split into two states of Mexico) was part of the original Spanish Las Californias.

Non-Spanish-speaking immigrants who 1) became naturalized Mexican citizens, 2) married Californios, and 3) converted to Catholicism may be included in a secondary, looser definition of Californio. Such residents, by these actions, became eligible to own land and receive rancho grants from the Mexican government. Most such grants occurred after mission secularization in the 1830s. An even looser definition may include descendants of Californios, especially those who married other Californio descendants.

The much larger population of non-Spanish-speaking indigenous peoples of California who lived in the area prior to and during the Californio era were not Californios. Neither were non-Spanish-speaking resident foreigners. Many Californios, however, were the California-born children of non-Spanish speakers who married Spanish speakers. Such spouses usually also converted to the Catholic faith and, after Mexico became independent of Spain in 1821, often became naturalized Mexican citizens.

The military, religious and civil components of pre-1848 Californio society were embodied in the thinly-populated presidios, missions, pueblos and ranchos.[2] Until they were secularized, the twenty-one Spanish missions of California, with their thousands of more-or-less captive native converts, controlled the most (about 1,000,000 acres (4,000 km2) per mission) and best land, had large numbers of workers, grew the most crops and had the most sheep, cattle and horses. After secularization, the Mexican authorities divided most of the mission lands into new ranchos and granted them to Mexican citizens (including many Californios) resident in California.

The Spanish colonial and later Mexican national governments encouraged settlers from the northern and western provinces of Mexico, but few attempted to cross the harsh Sonoran Desert. People from other parts of Latin America (most notably Peru and Chile) did settle in California. However, only a few official colonization efforts were ever undertaken—notably the second expedition of Juan Bautista de Anza (1775–1776), which established the first secular pueblo of San Jose.

Children of those few early settlers and retired soldiers became the first Californios. Sporadic colonization efforts continued under Mexican rule, including the Hijar-Padres group of 1834.[3] One genealogist estimated that, by 2004, between 300,000 and 500,000 Californians were descendants of Californios.[1]

Society and customs

Government

Alta California ("Upper California") was nominally controlled by a national-government appointed governor.[4] The governors of California were at first appointed by the Viceroy (nominally under the control of the Spanish kings), and after 1821 by the approximate 40 Mexican Presidents from 1821 to 1846. The costs of the minimum Alta California government were mainly paid by means of a roughly 40–100% import tariff collected at the entry port of Monterey.

The other center of Spanish power in Alta California was the Franciscan friars who, as heads of the 21 missions, often resisted the powers of the governors.[5] None of the Franciscan friars were Californios, however, and their influence rapidly waned after the secularization of the missions in the 1830s.

The instability of the Mexican government (especially in its early years), Alta California's geographic isolation, the growing ability of the Alta California's inhabitants to generally make a success of immigrating and an increase in the Californio population created a schism with the national government. As Spanish and Mexican period immigrants were succeeded in number by those that increasing lost an affinity with the national government, an environment developed that did not suppress disagreement with the central government. Governors had little material support from far-away Mexico to deal with Alta Californians, who were left to resolve situations themselves. Mexico-born governor Manuel Victoria was forced to flee in 1831, after losing a fight against a local uprising at the Battle of Cahuenga Pass.

As Californios matured to adulthood and increasingly assumed positions of power in the Alta California government (including that of governor), rivalries emerged between northern and southern regions. Several times, Californio leaders attempted to break away from Mexico, most notably Juan Bautista Alvarado in 1836. Southern regional leaders, led by Pio Pico, made several attempts to relocate the capital from Monterey to the more populated Los Angeles.[6]

Foreigners

The independence-minded Californios were also influenced by the increasing numbers of immigrant foreigners (mostly English and French, Americans were grouped with the "English"), who integrated with the Californios, becoming Mexican citizens and gaining land either independently granted to them or through marriage to Californio women; involvement in local politics was inevitable.[7]

For example, the American Abel Stearns was an ally of the Californio José Antonio Carrillo in the 1831 Victoria incident, yet sided with the southern Californians against the Californio would-be governor Alvarado in 1836. Alvarado recruited a company of Tennessean riflemen, many of them former trappers who had settled in the Monterey Bay area. The company was led by another American, Isaac Graham; the Americans refused to fight against fellow Americans. Alvarado was forced to negotiate a settlement.

Ethnic variety

Californios included the Castilian descendants of agricultural settlers and retired escort soldiers deployed from what today is Mexico. Other groups were of mixed ethnicities, usually Mestizo (Spanish and Native American) or mixed African-American and Indian backgrounds, who were often distinguished by the title, "Sonoran". Like the depictions of the popular shows like Zorro, true, historical Californios were of "pure" Castilian ancestry. In the beginning, most with unmixed Spanish ancestry were Franciscan priests, along with career government officials and military officers who did not remain in California.[8]

According to mission records (marriage, baptisms, and burials) as well as Presidio roster listings, several "leather-jacket" soldiers (soldados de cuero) operating as escorts, mission guards, and other military duty personnel were described as europeo (i.e., born in Europe), while most of the civilian settlers were of mixed origins (coyote, mulatto, etc.). The term "mestizo" was rarely if ever used in mission records, the more common terms being "indio", "europeo", "mulatto", "coyote", "castizo" and other caste terms. An example of the number of European-born soldiers is the twenty-five from Lieutenant Pedro Fages detachment of Catalonian Volunteers. Most of the soldiers on the Portola-Serra expedition of 1769 and the de Anza expeditions of 1774 and 1775 were recruited from the Spanish Army infantry regiments then stationed in Mexico. Many of them were assigned to garrison the presidios, then retired at the end of their ten-year enlistments, and remaining in California. Because there were many more men than women among the Spanish soldiers and settlers, some men who stayed in California married native Californian women who had converted to Christianity at the missions.

Family and education

The family was characteristically patriarchal, with the son regardless of age, deferring to his father's wishes.[7] Women had full rights of property ownership and control unless she was married or had a father—the males had almost complete control of all family members.[5] A formal education system in California had yet to be created so it fell to the individual families to educate their children among them, traditionally done by the priests or hired private tutors; few early immigrants knew how to read or write, so only a few hundred inhabitants could.[2]

Women in Californio Society

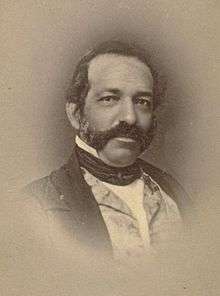

Women in Californio society are often heavily romanticized as the young Spanish women that are so commonly seen in extravagant dresses in movies and television. They are commonly characterized by their beauty and fun loving nature, while also being very sheltered and protected.[9] While some women at the pinnacle of Californio social standing did manage to live this kind of life it was very rare among indigenous peoples, most of whose women worked to help their families both inside and outside the home. See the top gallery for an 1867 photograph of Josepha Bandini de Carrillo, the Californio daughter of Juan Bandini and wife of Pedro C. Carrillo.

The social life of Californio society was extremely important in both politics and business, and women played an important but overlooked part in these interactions. They helped facilitate these interactions for their husbands, and therefore themselves, to move up in the social and power rankings of Californio society. This ability to shape social situations was a sought after trait when looking for a spouse, as prominent men knew the power their new wife would have in their future dealings[10]

As women played a key role in the development of Alta California and it's social interactions they continued this role into its transition from a Mexican territory to an American possession. As foreign non-Spanish speaking men moved into California, who wished to insert themselves into the upper echelons of already established social hierarchy, they began to use marriage with the women of established Californio families as a way to join this hierarchy.[10] Intermarriages between Californios and foreigners was common during the time of Mexican rule and quickly became even more common after the American annexation and Gold Rush in California. These intermarriages worked to combine the cultures of American settlers and merchants with that of the declining Californio society. These marriages though were not enough to prevent the descent into irrelevance of Californio power in California or the racism and attacks on the people of Mexican heritage later.

Repopulation

The Spanish colonial government, and later, Mexican officials encouraged through recruitment civilians from the northern and western provinces of Mexico such as Sonora. This was not well received by Californios, and was one of the factors leading to revolt against Mexican rule. Sonorans came to California despite the area's isolation and the lack of central government support. Many of the soldier's wives considered California to be a cultural wasteland and a hardship assignment. An incentive for the soldiers that remained in California after service was the opportunity to receive a land grant that probably was not possible elsewhere. This made most of California's early settlers military retirees with a few civilian settlers from Mexico. Since it was a frontier society, the initial rancho housing was characterized as rude and crude—little more than mud huts with thatched roofs. As the rancho owners prospered these residences could be upgraded to more substantial adobe structures with tiled roofs. Some buildings took advantage of local tar pits (La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles) in an attempt to waterproof roofs. Restoration of these Today, often suffer from a perception that results in a grander representation than if they had been constructed during the Californio period.[11]

The concession of land

Before Mexican independence in 1821, 20 "Spanish" land grants had been issued (at little or no cost) in all of Alta California;[7] many to "a few friends and family of the Alta California governors". The 1824 Mexican General Colonization Law established rules for petitioning for land grants in California; and by 1828, the rules for establishing land grants were codified in the Mexican Reglamento (Regulation). The Acts sought to break the monopoly of the Catholic Franciscan missions and possibly entice increased Mexican settlement. When the missions were secularized in 1834–1836 mission property and livestock were supposed to be mostly allocated to the Mission Indians.[11] Historical research shows that the majority of rancho grants were given to retired non-commissioned soldiers. The largest grants to Nieto, Sepulveda, Dominguez, Yorba, Avila, Grijalva, and other founding families were examples of this practice.[7]

Many of the foreign residents also became rancho grantees. Some were "Californios by marriage" like Stearns (who was naturalized in Mexico before moving north) and the Englishman William Hartnell. Others married Californios but never became Mexican citizens. Rancho ownership was possible for these men because, under Spanish/Mexican law, married women could independently hold title to property. In the Santa Cruz area, three Californio daughters of the inválido José Joaquín Castro (1768–1838) married foreigners yet still received grants to Rancho Soquel, Rancho San Agustin and Rancho Refugio.

Ranchos

In practice nearly all mission property and livestock became about 455 large Ranchos of California granted by the Californio authorities. The Californio rancho owners claimed about 8,600,000 acres (35,000 km2) averaging about 18,900 acres (76 km2) each. This land was nearly all originally mission land within about 30 miles (48 km) of the coast. The Mexican-era land grants by law were provisional for five years in order for the terms of the law could reasonably be fulfilled. The boundaries of these ranchos were not established as they came to be in later times predominately based on what could be understood as figurative boundaries. They were based on just where another granted owner considered the end of their land, lands or vegetation landmarks.[12] Conflict was bound to occur when these land grants were reviewed under United States control. Title to some grants under United States control were rejected[13] based on questionable documents especially when with predated documents, that could have been created post-United States occupancy in January 1847.[11][14]

Rancho culture

After agriculture, cattle, sheep and horses were established by the Missions, Friars, soldiers and Mission Indians the Rancho owners dismissed the Friars and the soldiers and took over the Mission land and livestock starting in 1834—the Mission Indians were left to survive however they could. The rancho owners tried to live in a grand style they perceived of the wealthy hidalgos in Spain. They expected the non-rancho owning population to support this lifestyle.[7] Nearly all males rode to where ever they were going at nearly all times making them excellent riders. They indulged in many fiestas, fandangos, rodeos and roundups as the rancho owners often went from rancho to rancho on a large horse bound party circuit. Weddings, christenings, and funerals were all "celebrated" with large gatherings.[11]

Taxes

Since the government depended on import tariffs (also called Custom duties and ad-valorem taxes) for its income there was virtually no property tax. Under Spanish/Mexican rule, all landowners were expected to the Diezmo, a compulsory tithe to the Catholic Church of one tenth of the fruits of agriculture and animal husbandry, business profits or salaries. Priest salaries and mission expenses were paid out of this money and/or collected goods.[11]

The mandatory Diezmo ended with the secularization of the missions, greatly reducing rancho taxes until the U.S. takeover. Today's state property tax system makes large self-supporting cattle ranches uneconomical in most cases.

Frequency of use of horses

Horses were plentiful and often left, after being broken in, to wander around with a rope around their neck for easy capture. It was not unusual for a rider to use one horse until it was exhausted, before switching its bridle to another horse—letting the first horse free to wander. Horse ownership for all except a few exceptional animals were almost community property. Horses were so common and of so little use that they were often destroyed to keep them from eating the grass needed by the cattle. California Indians later developed a taste for horse flesh as food and helped keep the number of horses under control.[11] An unusual use for horses was found in shucking wheat or barley. The wheat and its stems were cut from the gain fields by Indians bearing sickles. The grain with its stems still attached was transported to the harvesting area by solid wheeled ox-cart[15] (about the only wheeled transport in California) and put into a circular packed earth corral. A herd of horses were then driven into the same corral or "threshing field". By keeping the horses moving around the corral their hoofs would, in time, separate the wheat or barley from the chaff. Later the horses would be allowed to escape and the wheat and chaff were collected and then separated by tossing it into the air on a windy day so as to let the wind carry the chaff away. Presumably the wheat was washed before use to remove some of the dirt.[16]

The Indian work force

For these very few rancho owners and their families, this was the Californio's Golden Age, although for all the others much different.[7] Much of the agriculture, vineyards and orchards established by the Missions were allowed to deteriorate as the rapidly declining mission Indian population went from over 80,000 in 1800 to only a few thousand by 1846. Fewer Indians meant less food was required and the Franciscan Friars and soldiers supporting the missions disappeared after 1834 when the missions were abolished (secularized). After the Friars and soldiers disappeared, many of the Indians deserted the missions and returned to their tribes or found work elsewhere. The new ranchos often gave work to some of the former mission Indians. The "Savage tribes" worked for room, board and clothing (and no pay).[17] The former mission Indians performed the majority of the work herding cattle, planting and harvesting the ranchos' crops. The slowly increasing ranchos and Pueblos at Los Angeles, San Diego, Monterey, Santa Cruz, San Jose and Yerba Buena (now San Francisco) mostly only grew enough food to eat and to trade. The exceptions were the cattle and horses growing wild on unfenced range land. Originally owned by the missions they were killed for their hides and tallow.[18]

Leather and food

Leather, one of the most common materials available, was used for many products, including saddles, chaps, whips, window and door coverings, riatas (leather braided rope), trousers, hats, stools, chairs, bed frames, etc. Leather was even used for leather armor where soldiers' jackets were made from several layers of hardened leather sewn together. This stiff leather jacket was sufficient to stop most Indian arrows and worked well when fighting the Indians. Beef was a common constituent of most Californio meals and since it couldn't be kept long in the days before refrigeration, beef was often slaughtered to get a few steaks or cuts of meat. The property and yards around the ranchos were marked by the large number of dead cow heads, horns or other animal parts. Cow hides were kept later for trading purposes with Yankee or British traders who started showing up once or twice a year after 1825.[19] Beef, wheat bread products, corn (maize), several types of beans, peas and several types of squash were common meal items with wine and olive oil used when they could be found. The mestizo population probably subsisted mostly on what they were used to: corn or maize, beans, and squash with some beef donated by the rancho owners. What the average Native Americans ate is unknown since they were in transition from a hunter gatherer society to agriculturalists. Formerly, many lived at least part of the year on ground acorns, fish, seeds, wild game, etc. It is known that many of the ranchers complained about Indians stealing their cattle and horses to eat.[18]

Trade

From about 1769 to 1824 California averaged about 2.5 ships per year with 13 years showing no ships coming to California. These ships brought a few new settlers and supplies for the pueblos and Missions. Under the Spanish colonial government rules, trade was actively discouraged with non-Spanish ships. The few non-Indian people living in California had almost nothing to trade—the missions and pueblos were subsidized by the Spanish government. The occasional Spanish ships that did show up were usually requested by Californios and had Royal permission to go to California—bureaucracy in action. Prior to 1824, when the newly independent Mexico liberalized the trade rules[7] and allowed trade with non-Mexican ships, the occasional trading ship or U.S. whaler that put in to a California port to trade, get fresh water, replenish their firewood and obtain fresh meat and vegetables became more common. The average number of ships from 1825 to 1845 jumped to twenty-five ships per year versus the 2.5 ships per year common for the prior fifty years.[18]

The rancho society had few resources except large herds of Longhorn cattle which grew well in California. The ranchos produced the largest cowhide (called California Greenbacks) and tallow business in North America by killing and skinning their cattle and cutting off the fat. The cowhides were staked out to dry and the tallow was put in large cowhide bags. The rest of the animal was left to rot or feed the California grizzly bears that were common in California. With something to trade, and needing everything from nails, needles and almost anything made of metal to fancy thread and cloth that could be sewn into fancy cloaks or ladies' dresses, etc., they started trading with merchant ships from Boston, Massachusetts, Britain and other trading ports in Europe and the East Coast of the United States. The trip from Boston, New York City or Liverpool England averaged over 200 days one way. Trading ships and the occasional whaler put in to San Diego, San Juan Capistrano, San Pedro, San Buenaventura (Ventura), Monterey and Yerba Buena (San Francisco) after stopping and paying the import tariff of 50–100% at the entry port of Monterey, California. These tariffs or custom fees paid for the Alta California government. The classic book Two Years Before the Mast (originally published 1840) by Richard Henry Dana, Jr. gives a good first-hand account of a two-year sailing ship sea trading voyage to Alta California which he took in 1834-5. Dana mentions that they also took back a large shipment of California longhorn horns. Horns were used to make a large number of items during this period. (The eBook of Two Years Before the Mast is available at Gutenberg project[20] and at other sites.)

California was not alone in using the import duty to pay for its government as the U.S. import tariffs at this time were also the way the United States paid for most of its Federal Government. A U.S. average tariff (also called custom duties and ad valorem taxes) of about 25% raised about 89% of all Federal income in 1850.[21]

History

Early colonization

In 1769, Gaspar de Portolà and less than two hundred men, on expedition founded the Presidio of San Diego (military post). On July 16, Franciscan friars Junípero Serra, Juan Viscaino and Fernando Parron raised and 'blessed a cross', establishing the first mission in upper Las Californias, Mission San Diego de Alcalá.[22] Colonists began arriving in 1774.

Monterey, California was established in 1770 by Father Junípero Serra and Gaspar de Portolà (first governor of Las Californias province (1767–1770), explorer and founder of San Diego and Monterey). Monterey was settled with two friars and about 40 men and served as the capital of California from 1777 to 1849. The nearby Carmel Mission, in Carmel, California was moved there after a year in Monterey to keep the mission and its Mission Indians away from the Monterey Presidio soldiers. It was the headquarters of the original Alta California province missions headed by Father-President Junípero Serra from 1770 until his death in 1784—he is buried there. Monterey was originally the only port of entry for all taxable goods in California. All ships were supposed to clear through Monterey and pay the roughly 42% tariff (customs duties on imported goods before trading anywhere else in Alta California. The oldest governmental building in the state is the Monterey Custom House and California's Historic Landmark Number One.[23] The Californian, California's oldest newspaper, was first published in Monterey on August 15, 1846, after the city's occupation by the U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron on July 7, 1846.[24]

Late in 1775, Colonel Juan Bautista de Anza led an overland expedition over the Gila River trail he had discovered in 1774 to bring colonists from Sonora New Spain (Mexico) to California to settle two missions, one presidio, and one pueblo (town). Anza led 240 friars, soldiers and colonists with their families. They started out with 695 horses and mules and 385 Texas Longhorn bulls and cows—starting the cattle and horse industry in California. About 600 horses and mules and 300 cattle survived the trip. In 1776 about 200 leather-jacketed soldiers, Friars, and colonists with their families moved to what was called Yerba Buena (now San Francisco) to start building a mission and a presidio there. The leather jackets the soldiers wore consisted of several layers of hardened leather and were strong enough body armor to usually stop an Indian arrow. In California the cattle and horses had few enemies and plentiful grass in all but drought years and essentially grew and multiplied as feral animals—doubling roughly every two years. They partially displaced the Tule Elk and pronghorn antelope who had lived there in large herds previously.

Anza selected the sites of the Presidio of San Francisco and Mission San Francisco de Asís in what is now San Francisco; on his way back to Monterey, he sited Mission Santa Clara de Asís and the pueblo San Jose in the Santa Clara Valley but did not initially leave settlers to settle them. Mission San Francisco de Asís (or Mission Dolores), the sixth Spanish mission, was founded on June 29, 1776, by Lieutenant José Joaquin Moraga and Father Francisco Palóu (a companion of Junípero Serra).

On November 29, 1777, El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe (The Town of Saint Joseph of Guadalupe now called simply San Jose) was founded by José Joaquín Moraga on the first pueblo-town not associated with a mission or a military post (presidio) in Alta California. The original San Jose settlers were part of the original group of 200 settlers and soldiers that had originally settled in Yerba Buena (San Francisco). Mission Santa Clara, founded in 1777, was the eighth mission founded and closest mission to San Jose. Mission Santa Clara was 3 miles (5 km) from the original San Jose pueblo site in neighboring Santa Clara. Mission San José was not founded until 1797, about 20 miles (30 km) north of San Jose in what is now Fremont.

The Los Angeles Pobladores ("villagers") is the name given to the 44 original Sonorans—22 adults and 22 children—who settled the Pueblo of Los Angeles in 1781. The pobladores were agricultural families from Sonora, Mexico. They were the last settlers to use the Anza trail as the Quechans (Yumas) closed the trail for the next 40 years shortly after they had passed over it. Almost none of the settlers were españoles (Spanish); the rest had casta (caste) designations such as mestizo, indio, and negro. Some classifications were changed in the California Census of 1790, as often happened in colonial Spanish America.[25]

The settlers and escort soldiers who founded the towns of San José de Guadalupe, Yerba Buena (San Francisco), Monterey, San Diego and La Reina de Los Ángeles were primarily mestizo and of mixed Negro and Indian ancestry from the province of Sonora y Sinaloa in Mexico. Recruiters in Mexico of the Fernando Rivera y Moncada expedition and other expeditions later, who were charged with founding an agricultural community in Alta California, had a difficult time persuading people to emigrate to such an isolated outpost with no agriculture, no towns, no stores or developments of almost any kind. The majority of settlers were recruited from the northwestern parts of Mexico. The only tentative link with Mexico was via ship after the Quechans (Yumas) closed the Colorado River's Yuma Crossing in 1781. For the next 40 years, an average of only 2.5 ships per year visited California with 13 years showing no recorded ships arriving.

In Californio society, casta (caste) designations carried more weight than they did in older communities of central Mexico. One similar concept was the gente de razón, a term literally meaning "people of reason". It designated peoples who were culturally Hispanic (that is, they were not living in traditional Indian communities) and had adopted Christianity. This served to distinguish the Mexican Indio settlers and converted Californian Indios from the barbaro (barbarian) Californian Indians, who had not converted or become part of the Hispanic towns.[26] California's Governor Pío Pico was criticized for his alleged descent from mestizo and mulato (mulatto) settlers.

The end of Mexican rule

In the 1830s the newly formed Mexican government was experiencing difficulties having gone through several revolts, wars, and internal conflicts and a seemingly never ending string of Mexican Presidents. One of the problems in Mexico was the large amount of land controlled by the Catholic Church (estimated then at about one-third of all settled property) who were continually granted property by many land owners when they died or controlled property supposedly held in trust for the Indians. This land, as it gradually accumulated, was seldom sold as it cost nothing to keep, but could be rented out to gain additional income for the Catholic Church to pay its priests, Friars, Bishops etc. and other expenses. The Catholic Church was the largest and richest land owner in Mexico and its provinces. In California the situation was even more pronounced as the Franciscan Friars held over 90% of all settled property supposedly in trust for the Mission Indians.

In 1834 secularization laws [27] were enacted that voided the mission control of lands in the northern settlements under Mexican rule. The missions controlled over 90% of the settled land in California as well as directing thousands of Indians in herding livestock, growing crops and orchards, weaving cloth, etc. for the missions and the presidios and pueblo (town) dwellers. The mission lands and herds formerly controlled by the missions were usually distributed to the settlers around each mission. Since most had almost no money the land was distributed or granted free or at very little cost to friends and families (or those who paid the highest bribes) of the government officials.

The Californio Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, for example, was reputed to be the richest man in California before the California Gold Rush. Vallejo oversaw the secularization of Mission San Francisco Solano and the distributions of its roughly 1,000,000 acres (4,000 km2). He founded the towns of Sonoma, California and Petaluma, California, owned Mare Island and the future town site of Benicia, California and was granted the 66,622-acre (269.61 km2) Rancho Petaluma, the 84,000-acre (340 km2) Rancho Suscol and other properties by Governor José Figueroa in 1834 and later. Vallejo's younger brother, Jose Manuel Salvador Vallejo (1813–1876), was granted the 22,718-acre (91.94 km2) Rancho Napa and other additional grants known as Salvador's Ranch.[28] Over the hills of Mariano Vallejo's princely estate of Petaluma roamed ten thousand cattle, four to six thousand horses, and many thousands of sheep. He occupied a baronial castle on the plaza at Sonoma, where he entertained all who came with most royal hospitality and few travelers of note came to California without visiting him. At Petaluma he had a great ranch house called La Hacienda and on his home farm called Lachryma Montis (Tear of the Mountain), he built, about 1849, a modern frame house where he spent the later years of his life.

Vallejo tried to get the California State Capital moved permanently to Benicia, California on land he sold to the state government in December 1851. It was named Benicia for the General's wife, Francisca Benicia Carillo de Vallejo. The General intended that the prospective city be named "Francisca" after his wife, but this name was dropped when the former city of "Yerba Buena" changed its name to "San Francisco" on January 30, 1847. Benicia was the third site selected to serve as the California state capital, and its newly constructed city hall was California's capitol from February 11, 1853 to February 25, 1854. Vallejo gave the 84,000-acre (340 km2) Rancho Suscol to his oldest daughter, Epifania Guadalupe Vallejo, April 3, 1851, as a wedding present, when she married U.S. Army General John H. Frisbie. It is unknown what he gave as a wedding present when his two daughters Natalia and Jovita married the brothers Attila Haraszthy and Agoston Haraszthy on the same day—June 1, 1863.

In some cases particular mission land and livestock were split into parcels and then distributed by drawing lots. In nearly all cases the Indians got very little of the mission land or livestock. Whether any of the proceeds of these sales made its way back to Mexico City is unknown. These lands had been worked by settlers and the much larger settlements of local Native American Kumeyaay peoples on the missions for in some cases several generations. When the missions were secularized or dismantled and the Indians did not have to live under continued Friar and military control they were left essentially to survive on their own. Many of the Native Americans reverted to their former tribal existence and left the missions while others found they could get room and board and some clothing by working for the large ranches that took over the former mission lands and livestock. Many natives who had learned to ride horses and had a smattering of Spanish were recruited to be become vaqueros (cowboys or cattle herders) that worked the cattle and horses on the large ranchos and did other work. Some of these rancho owners and their hired hands would make up the bulk of the few hundred Californios fighting in the brief Mexican–American War conflicts in California. Some of the Californios and California Indians would fight on the side of the U.S. settlers during the conflict with some even joining the California Battalion.

Mexican Governors of California

The Californios had a succession of Mexican appointed governors who nearly all either died in office or were driven from office. Many of governors appointed by Mexico proved to be mediocre, autocratic and indifferent to Californio concerns or needs and were driven from office. The native Californio governors were usually self-appointed and acted as governor pro tempore till Mexico heard about the previous Governor's death or ouster and they could appoint a new governor or approve the existing governor—often a slow process. The Californios had such poor luck with Mexican troops (often unpaid convicts) and Mexican appointed governors that many resented Mexican interference in what they considered their internal affairs.

- List of Governors

- 1822–1825: Luis Antonio Argüello (born in San Francisco, he was the first native–born Californio to govern Alta California)

- 1825–1831: José María de Echeandía Mexico appointed; first of two terms

- 1831–1832: Manuel Victoria Mexico appointed; forced from office after one year

- 1832: Pío Pico native-born Californio, native of San Diego and favored British acquisition of California, moved capital from Monterey to Los Angeles

- 1832–1833: Agustín V. Zamorano a secretary to Manuel Victoria and was governor pro tempore of northern California and José María de Echeandía Echeandía reappointed governor pro tempore but could only gain control of southern California. Both were only temporary appointments

- 1833–1835: José Figueroa Mexico appointed; started secularization of Missions; died in office

- 1835: José Castro Californio; governor pro tempore

- 1836: Nicolás Gutiérrez Mexico appointed; governor pro tempore

- 1836: Mariano Chico Mexican governor expelled from office after three months and exiled to Mexico

- 1836: Nicolás Gutiérrez Mexico appointed; governor pro tempore reassumed office

- 1836–1837: Juan Bautista Alvarado Californio; ousted Gutierrez

- 1837–1838: Carlos Antonio Carrillo Californio governor pro tempore

- 1838–1842: Juan Bautista Alvarado Californio, reassumed office

- 1842–1845: Manuel Micheltorena Mexico appointed governor came in with 300 troops and served from December 30, 1842, until his ouster in 1845 when he and his troops (most unpaid convicts) were driven back to Mexico.

- 1845–1846: Pío Pico Californio, reassumed office

- 1846–1847: José María Flores Mexican Army officer, secretary to Micheltorena; fled California when Mexican American War started

- 1847: Andrés Pico Californio, commanded Californio lancers against General Kearny; provisional governor of rebellion; signed Treaty of Cahuenga January 12, 1847 ceasing strife in California.

The Mexican–American War

Prior to the Mexican–American War the Californios forced the Mexican appointed governor, Manuel Micheltorena, to flee back to Mexico with most of his troops. Pío Pico, a Californio, was the governor of California during the conflict.

The Pacific Squadron, the United States Naval force stationed in the Pacific was instrumental in the capture of Alta California in the Mexican–American War of 1846–1848 after war was declared on April 24, 1846. The American navy with its force of 350–400 U.S. Marines and "bluejacket" sailors on board several U.S. Naval ships near California were essentially the only significant United States military force on the Pacific Coast in the early months of the Mexican–American War. The British navy Pacific Station ships in the Pacific had more men and were more heavily armed than the U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron, but did not have orders to help or hinder the occupation of California. New orders would have taken almost two years to get back to the British ships. The Marines were stationed aboard each ship to assist in ship-to-ship combat, as snipers in the rigging, and to defend against boarders. They could also be detached for use as armed infantry. In addition, there were some "bluejacket" sailors on each ship that could be detached for shore duty as artillery crews and infantry, leaving the ship functional though short handed. The artillery used were often small naval cannon converted to land use. The Pacific Squadron had orders, in the event of war with Mexico, to seize the ports in Mexican California and elsewhere along the Pacific Coast.

The only other United States military force in California at the time was a small exploratory expedition led by Lieutenant Colonel John C. Frémont, made up of 30 topographical, surveying, etc. army troops and about 25 men hired as guides and hunters. The Frémont expedition had been dispatched to California, in 1845, from the United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers.

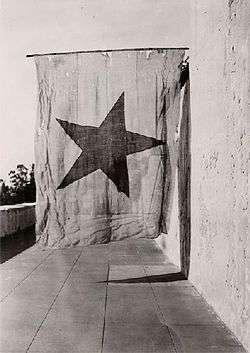

Rumors that the Californio government in California was planning to arrest and deport many of the new residents as they had in 1844 led to a degree of uncertainty. On June 14, 1846, thirty-three settlers in Sonoma Valley took preemptive action and captured the small Californio garrison of Sonoma, California without firing a shot and raised a homemade flag with a bear and star (the "Bear Flag") to symbolize their taking control. The words "California Republic" appeared on the flag but were never officially adopted by the insurgents. The present Flag of California is based on the original "Bear Flag".

Their capture of the small garrison in Sonoma was later called the "Bear Flag Revolt".[29] The Republic's only commander-in-chief was William B. Ide,[30] whose command lasted twenty-five days. On June 23, 1846, Frémont arrived from the future state of Oregon's border with about 30 soldiers and 30 scouts and hunters and took command of the "Republic" in the name of the United States. Frémont began to recruit a militia from among the new settlers living around Sutters Fort to join with his forces. Many of these settlers had just arrived over the California Trail and many more would continue to arrive after July 1846 when they got to California. The Donner Party were the last travelers on the trail in late 1846 when they were caught by early snow while they were trying to get across the Sierras.

Under orders from John D. Sloat, Commodore of the Pacific Squadron, the U.S. Marines and some of the bluejacket sailors from the U.S. Navy sailing ships USS Savannah with the Cyane and Levant captured the Alta California capital city of Monterey, California on July 7, 1846. The only shots fired were salutes by the U.S. Navy ships in the harbor to the U.S. flag now flying over Monterey. Two days later on July 9, USS Portsmouth, under Captain John S. Montgomery, landed 70 Marines and bluejacket sailors at Clark's Point in San Francisco Bay and captured Yerba Buena (now named San Francisco) without firing a shot.

On July 11 the British Royal Navy sloop HMS Juno entered San Francisco Bay, causing Montgomery to man his defenses. The large British ship, 2,600 tons with a crew of 600, man-of-war HMS Collingwood, flagship under Sir George S. Seymour, also arrived at about this time outside Monterey Harbor. Both British ships observed, but did not enter the conflict.[31]

Shortly after July 9, when it became clear the US Navy was taking action, the short-lived Bear Flag Republic was converted into a United States military occupation and the Bear Flag was replaced by the U.S. flag. Commodore Robert F. Stockton took over as the senior U.S. military commander in California in late July 1846 and asked Frémont's force of California militia and his 60 men to form the California Battalion with U.S. Army pay and ranks with Fremont in command. The California "Republic" disbanded and William Ide enlisted in the California Battalion, when it was established in late July 1846, as a private.

The first job given to the California Battalion and was to assist in the capture of San Diego and Pueblo de Los Angeles. On July 26, 1846, Lt. Col. J. C. Frémont's California Battalion of about 160 boarded the sloop USS Cyane, under the command of Captain Samuel Francis Du Pont, and sailed for San Diego. They landed July 29, 1846, and a detachment of Marines and blue-jackets, followed shortly by Frémont's California Battalion from Cyane, landed and took possession of the town without firing a shot. Leaving about 40 men to garrison San Diego, Fremont continued on to Los Angeles where on August 13, with the Navy band playing and colors flying, the combined forces of Stockton and Frémont entered Pueblo de Los Angeles, without a man killed nor shot fired. U.S. Marine Lieutenant Archibald Gillespie, Frémont's second in command, was appointed military commander of Los Angeles with an inadequate force from 30 to 50 California Battalion troops stationed there to keep the peace.

In Pueblo de Los Angeles, the largest city in California with about 3,000 residents, things might have remained peaceful, except that Major Gillespie placed the town under martial law, greatly angering some of the Californios. On September 23, 1846, about 200 Californios under Californio Gen. José María Flores staged a revolt, the Siege of Los Angeles, and exchanged shots with the Americans in their quarters at the Government House. Gillespie and his men withdrew from their headquarters in town to Fort Hill which, unfortunately, had no water. Gillespie was caught in a trap, badly outnumbered by the besiegers. John Brown, an American, called by the Californios Juan Flaco,[32] meaning "Lean John", succeeded in breaking through the Californio lines and riding by horseback to San Francisco Bay (a distance of almost 400 miles (640 km)) in an amazing 52 hours where he delivered to Stockton a dispatch from Gillespie notifying him of the situation. Gillespie, on September 30, finally accepted the Californio terms and departed for San Pedro with his forces, weapons, flags and two cannon (the others were spiked and left behind). Gillespie's men were accompanied by the exchanged American prisoners and several non-Californio residents.[33]

It would take about four months of intermittent sparing before Gillespie could again raise the same American flag originally flown over Los Angeles. Los Angeles was retaken without a fight on January 10, 1847.[34] Following their defeat at the Battle of La Mesa, the Californio government signed the Treaty of Cahuenga, which ended the war in California on January 13, 1847. The main Californio military force, known as the Californio lancers, was disbanded. On January 16, 1847, Commodore Stockton appointed Frémont military governor of U.S. territorial California.

Some Californios fought on both sides of the conflict (U.S. and Mexico). The battlefield memorials attest to the heroic fight and loss on both sides.

Californio battles

Most towns in California surrendered without a shot being fired on either side. What little fighting that did occur usually involved small groups of disaffected Californios and small groups of soldiers, marines or militia

- 1846

- Battle of Dominguez Rancho, October 9, 1846. José Antonio Carrillo, near Los Angeles, leads Californio forces against 350 marines and sailors who retreated.

- Battle of San Pasqual, 6 December 1846. US Cavalry General Stephen Kearny's dragoons, after a grueling journey across New Mexico and the Mojave Desert, cross into California with about 100 men and are joined by Kit Carson's 20 scouts and about 40 men under Gillespie north of San Diego. In a poorly thought out and uncoordinated attack with wet powder and worn out mules Kearny loses about 19 of his men in a fight with about 150 Californio lancers led by Andrés Pico—brother of Pio Pico. Californio casualties are unknown. By the time reinforcements came from U.S. forces in San Diego, the Californio forces were already gone.[34]

Battle of San Pascual, a rousing Californio victory led by Don Andrés Pico against a superior force led by Gen. Stephen W. Kearny. Kearny had underestimated Californio anger toward John C. Fremont, and his troops were tired after crossing the desert from New Mexico.

Battle of San Pascual, a rousing Californio victory led by Don Andrés Pico against a superior force led by Gen. Stephen W. Kearny. Kearny had underestimated Californio anger toward John C. Fremont, and his troops were tired after crossing the desert from New Mexico. - Temecula Massacre, December 1846. Californios and Cahuilla Indians combine to wipe out a party of Pauma Band Luiseño Indians responsible for a massacre of eleven Californios, near Temecula.[35]

- 1847

- January 5, 1847. Frémont near the San Buenaventura Mission, with about 400 men and six field pieces, disperses a force of 60–70 Californio Lancers.[34]

- Battle of Rio San Gabriel, January 8, 1847. Stephen Kearny and Stockton's combined force of about 600 men (about a battalion equivalent) defeat the roughly 160-man Californio Lancer force near Los Angeles. Casualties are about one man on each side.

- Battle of La Mesa, January 9, 1847. Kearny and Robert F. Stockton's combined US forces defeat the Californios in the final battle in California, at present day Montebello, east of Los Angeles. Casualties are about one man on each side.

In late December, 1846, while Fremont was in Santa Barbara, Bernarda Ruíz de Rodriguez, a wealthy educated woman of influence and town matriarch, asked to speak with him. She advised him that a generous peace would be to his political advantage. Fremont later wrote of this 2-hour meeting, "I found that her object was to use her influence to put an end to the war, and to do so upon such just and friendly terms of compromise as would make the peace acceptable and enduring".[36][37] The next day, Bernarda accompanied Fremont south.

On January 11, 1847, General Jose Maria Flores turned over his command to Andrés Pico and fled. On January 12, Bernarda went alone to Pico's camp and told him of the peace agreement she and Fremont had forged. Fremont and two of Pico's officers agreed to the terms for a surrender, and Jose Antonio Carrillo penned Articles of Capitulation in both English and Spanish.[38] The first seven articles were nearly the verbatim suggestions of Bernarda.

On January 13, at a deserted rancho at the north end of Cahuenga Pass (modern-day North Hollywood), John Fremont, Andres Pico and six others signed the Articles of Capitulation, which became known as the Treaty of Cahuenga. Fighting ceased, thus ending the war in California.[39][40]

Californios after U.S. annexation

In 1848, Congress set up a Board of Land Commissioners to determine the validity of Mexican land grants in California. California Senator William M. Gwin presented a bill that, when approved by the Senate and the House, became the Act of March 3, 1851.[41] It stated that unless grantees presented evidence supporting their title within two years, the property would automatically pass back into the public domain.[42]

Rancho owners cited the articles VIII and X of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, wherein it guaranteed full protection of all property rights for Mexican citizens—with an unspecified time limit.[43][44]

Many ranch owners with their thousands of acres and large herds of cattle, sheep and horses went on to live prosperous lives under U.S. rule. Former commander of the California Lancers Andrés Pico became a U.S. citizen after his return to California and acquired the Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando ranch which makes up large part of what is present day Los Angeles. He went on to become a California State Assemblyman and later a California State Senator. His brother former governor of Alta California (under Mexican rule) Pío Pico also became a U.S. citizen and a prominent ranch owner/businessman in California after the war. Many others were not so fortunate as droughts decimated their herds in the early 1860s and they could not pay back the high cost mortgages (poorly understood by the mostly illiterate ranchers) they had taken out to improve their lifestyle and subsequently lost much or all of their property when they could not be repaid.

Californios did not disappear. Some people in the area still have strong identities as Californios. For instance, numerous people descended from the Sepulveda family meet and keep in contact via the Internet. Thousands of people who are descended from the Californios have well-documented genealogies of their families.

The history of Californios has fueled the politically volatile issues of the mid-twentieth century, such as La Raza and other organized Chicano activists, who depict Mexicans or Hispanics as the state's original people. They discount the claims to this status by the approximate 50,000 to 80,000 indigenous peoples, such as Coast Miwok, Ohlone, Wintun, Yokuts and other Native American ancestors. Many of these tribes' ancestors inhabited the California region for thousands of years before European contact.

Other Mexican activists claim there was an integrated society of Mexicans, Indians, Mestizos and American immigrants, which had evolved over 77 years beginning with the founding of Misión San Diego in the Alta California territory in 1769.

The developing agricultural economy of California allowed many Californios to continue living in pueblos alongside Native peoples and Mexicanos well into the 20th century. These settlements grew into modern California cities, including Santa Ana, San Diego, San Fernando, San Jose, Monterey, Los Alamitos, San Juan Capistrano, San Bernardino, Santa Barbara, Arvin, Mariposa, Hemet and Indio.

From the 1850s until the 1960s, the Hispanics (of Spanish, Mexican and regional Native American origins) lived in relative autonomy. They practiced a degree of social racial segregation by custom, while maintaining Spanish-language newspapers, entertainment, schools, bars, and clubs. Cultural practices were often tied to local churches and mutual aid societies. At some point in the early 20th century, the official recordkeepers (census takers, city records, etc.) began grouping together all Californios, Mexicanos, and Native (Indio) peoples with Spanish surnames under the terms "Spanish", "Mexican", and sometimes, "colored"; some Californios even intermarried with Mexican Americans (those whose ancestors were refugees escaping the Mexican Revolution in 1910).

Alexander V. King has estimated that there were between 300,000 and 500,000 descendants of Californios in 2004.[1]

Californios in the California Gold Rush

In 1848, gold is discovered at Sutter’s Mill, near Coloma, California.[45] This discovery was made only nine days before the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, which turned over California to the United States as a result of the Mexican–American War.[46]

A group of Californio prospectors led by Antonio F. Coronel set out from Los Angeles to prospect for gold in Campo Seco.[45] After a change of plans, the group spent a few months in campo de Estanilo mining alongside mostly Californios. After this, they left to head north into Sonoma, where one of the group members is ambushed and violently attacked, left for dead with only Colonel to tend to him.[45] This ambush and lack of response by any authorities or other White Americans shows how Californios were tragically the victims of Euro-American vigilante violence and often forced to leave their native land.

Large Influx of Foreigners Diluting Californio Population

From the end of 1849 to the end of 1852, the population in California increased from 107,000 to 264,000 due to the California Gold Rush. In early 1849, approximately 6,000 Mexicans, many of whom were Californios who remained after the United States had annexed the territory, were prospecting for gold in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.[47] Although the territory they were in had up until recently been Mexican land, Californios and other Mexicans very quickly became the minorities and were seen as the foreigners. Once the Gold Rush had truly started in 1849, the campsites were segregated by nationality, further establishing the fact that "Americans" had taken the title as the majority ethnicity in Northern California.[45] Because the Californio "foreigners" so quickly became a minority, their claims to land protected under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo when miners overran their land and squatted.[48] Any protests by Californios were quickly put down by hastily formed Euro-American militias, so any legal protection provided by the new California legislature was ineffective when the threat of violence and lynchings loomed.[48] Even if Californios were able to win their land back in court, often lawyer's fees cost large sums of land that left them with a fraction of their former wealth.

Working Conditions

Many Latino miners were experienced due to learning a "dry-digging" technique in the Mexican mining state of Sonora.[49] Their early success due praise and respect from Euro-American miners, they eventually became jealous and used threats and violence to force Mexican workers out of their plots and into less lucrative ones.[49] In addition to these informal forms of discrimination, Anglo miners also worked to establish Jim Crow-like laws to prevent Latinos from mining altogether.[49] In 1851, mob violence as well as the Foreign Miners' Tax discussed below forced between five thousand and fifteen thousand foreigners out of work in just a few months.[45]

According to Antonio F. Coronel's accounts, there was systematic race-influenced violence conducted by Americans to force out Californios and other Latinos. One account tells of a Frenchman and "un español" being lynched for supposed theft in 1848. Despite offers by Californios to replace the reported amount of gold stolen, they were still hanged.[45] In addition, later in the Gold Rush, Coronel and his group found a rich vein of gold on the American River. When Euro-Americans caught wind of this, the invaded the claim armed and insisted it was their plot, forcing out Colonel and ending his mining career.[45] Accounts like these show the harsh and violent living and working conditions that Californios were faced with during the Gold Rush. Discriminatory and racist treatment and laws as well as being so vastly outnumbered forced them out of their native lands despite assurances by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that they could remain.

Foreign Miners' Tax

In response to the Mexican resistance to the American population, white miners called for something to be done about the "Sonoran" miner "problem". In response, in 1850, the Californian government introduced a tax on foreign miners who were working plots, called the Foreign Miners' Tax Law. The claimed purpose of the tax was to fund the government's efforts to protect the foreign workers. There are conflicting reports on the amount of the tax ranging from $20 to $30 per month.[45] This extremely high tax forced all but the most successful Latinos to stop mining as they were unable to obtain enough gold to make mining profitable. This left only the most successful of the Mexican prospectors, who ironically were the ones who drew the most ire from the Euro-American miners initially. By 1851, when the tax law was repealed, approximately two-thirds of the Latinos and Californios that had been living and working in mining areas had been driven out by the tax.[50] After repealing the $20 or $30 per month tax, the California legislature instituted a much more reasonable $3 per month tax in 1852.[49] However, at this point, many of the Californios had already been driven out of their homes and mining plots, making it somewhat of a moot point. These taxes were for the most part only enforced against Latinos, including Californios, and the Chinese, but not any other foreign, but white Europeans, showing systematic racism on the part of the newly formed California Legislature.

Notable Californios

- Rosario E. Aguilar

- José Antonio Aguirre (early Californian)

- Pedro de Alberni

- Juan Bautista Alvarado, governor

- José María Alviso, grantee of Rancho Milpitas, Alcalde of San José

- Concepción Argüello

- Santiago Arguello

- Santiago E. Arguello

- Avila family of California

- Arcadia Bandini, co-founder of Santa Monica, California

- Juan Bandini

- Berreyesa family, various early settlers holding land grants (between them, José de los Reyes Berreyesa)

- Diego de Borica

- Dionisio Botiller

- José Raimundo Carrillo

- José Antonio Carrillo

- José Castro, general of the Mexican army in Alta California

- Víctor Castro

- Eulogio F. de Celis

- Joseph Chiles

- Antonio F. Coronel

- Ygnacio Coronel

- Leonardo Cota

- Manuel Dominguez

- Narciso Durán

- José María de Echeandía

- José Antonio Estudillo

- José Joaquín Estudillo

- José María Estudillo

- José Figueroa

- José María Flores

- Juan Flores

- Myrtle Gonzalez, silent-era movie actress, descendant of Californios

- José de la Guerra y Noriega

- Antonio Maria de la Guerra

- Francisco Guerrero (politician)

- Nicolás Gutiérrez

- Francisco de Haro

- William Edward Petty Hartnell, also known as Don Guillermo Arnel

- José Joaquin Jimeno

- Fermín Lasuén

- Robert Livermore, namesake of Livermore, California

- José del Carmen Lugo

- Eulalia Perez de Guillén Mariné

- Juan María Marrón

- Juan Prado Mesa

- Manuel Micheltorena

- Juana Briones de Miranda

- Esteban Munras – (1798–1850) was a 19th-century Spanish artist, probably best known for the vibrantly-colored frescoes that adorn the chapel interior at Mission San Miguel Arcángel in California.

- Joaquin Murrieta

- Manuel Nieto

- Romualdo Pacheco, 12th Governor of California

- Luís María Peralta, Peralta Adobe in San Jose, recipient of the Rancho San Antonio (Peralta) land grant in the San Francisco East Bay

- Ignacio Peralta

- Andrés Pico

- José Maria Pico

- Pío Pico, the last Mexican governor of Alta California, namesake of Pico Rivera, California

- Luis Manuel Quintero

- Manuel Requena

- Juan Francisco Reyes (soldier)

- Louis Robidoux, namesake of Mount Rubidoux, held Rancho Jurupa and Rancho San Jacinto y San Gorgonio

- José Antonio Roméu

- José González Rubio – (1804–1875) Roman Catholic friar prominent in the early history of California.

- Francisco María Ruiz

- José de la Cruz Sánchez – (1799–1878) was the eleventh Alcalde of San Francisco in 1845.

- Francisco Sanchez (politician)

- Tomas Avila Sanchez

- Vicente de Santa Maria

- Vicente Francisco de Sarría

- José Francisco de Paula Señan

- Francisco Xavier Sepulveda

- Juan Jose Sepulveda

- Francisco Sepulveda

- Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, the namesake of Vallejo, California

- Tiburcio Vasquez, bandit

- Jose Maria Verdugo, recipient of Rancho San Rafael land grant

- Manuel Victoria

- Bernardo Yorba, major land grant recipient, namesake of Yorba Linda, California

- Jose Antonio Yorba, major land grant recipient

Other notable people in Alta California

- José Romo de Vivar (settler in Arizona)

- José Joaquín Moraga (born in Arizona)

- José Francisco Ortega (founder of large Californio family)

- José de Urrea (born in Arizona)

Californios in literature

- Richard Henry Dana, Jr., recounted aspects of Californio culture which he saw during his 1834 visit as a sailor in Two Years Before the Mast.

- Joseph Chapman, a land realtor noted as the first Yankee to reside in the old Pueblo de Los Angeles in 1831, described Southern California as a paradise yet to be developed. He mentions a civilization of Spanish-speaking colonists, "Californios", who thrived in the pueblos, the missions, and ranchos.

- Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton, The Squatter and the Don, a novel set in 1880s California, depicts a very wealthy Californio family's legal struggles with immigrant squatters on their land.[51] The novel was based on the legal struggles of General Mariano G. Vallejo, a friend of the author. The novel depicts the legal process by which Californios were often "relieved" of their land. This process was long (most Californios spent up to 15 years defending their grants before the courts), and the legal fees were enough to make many Californios landless. Californios resented having to pay land taxes to United States officials, because the principle of paying taxes for land ownership did not exist in Mexican law. In some cases Californios had little available capital, because their economy had operated on a barter system; they often lost land because of the inability to pay the taxes.[52] They could not compete economically with the European and Anglo-American immigrants who arrived in the region with large amounts of cash.

A portrayal of Californio culture is depicted in the novel Ramona (1884), written by Helen Hunt Jackson.

The fictional character of Zorro has become the most identifiable Californio due to short stories, motion pictures and the 1950s television series. The historical facts of the era are sometimes lost in the story-telling.

See also

Culture, race and ethnicity

History and government

- History of California

- History of California before 1900

- Provincias Inte rnas

- California Republic

- Conquest of California

References

- 1 2 3 King, Alexander V. (January 2004). "Californio Families, A Brief Overview". San Francisco Genealogy. Society of Hispanic Historical & Ancestral Research.

- 1 2 Harrow, Neal; California Conquered: The Annexation of a Mexican Province, 1846–1850; pp. 14–30; University of California Press; 1989; ISBN 978-0-520-06605-2

- ↑ Hutchinson, C. A. (1969). Frontier settlement in Mexican California: The Híjar-Padrés colony and its origins, 1769-1835. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ↑ Howard Lamar, editor. The Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West, (1977). Harper & Row, New York, pp. 149, 154.

- 1 2 Werner, Michael S., Editor; Concise Encyclopedia of Mexico; Women's Status and Occupation". pp. 886–898; Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers; ISBN 1-57958-337-7

- ↑ Howard Lamar, editor. The Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West, (1977). Harper & Row, New York, p. 677.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Howard Lamar, editor. The Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West, (1977). Harper & Row, New York, p. 154.

- ↑ Mason, The Census of 1790; Gostin, Southern California Vital Records; Haas, Conquests and Historical Identities in California; and Pitt, Decline of the CaliforniosCalifornia Spanish Genealogy – California Census 1790.

- ↑ Langum, David J. "Californio Women and the Image of Virtue". Southern California Quarterly 59.3 (1977): 245–250.

- 1 2 Sánchez, Rosaura (1995). Telling Identities: The Californio testimonios. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 210–220. ISBN 0-8166-2559-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hoffman, Lola B.; California Beginnings; California State Department of Education; 1848; p. 151

- ↑ Walton Bean, California: An Interpretive History, Second Ed., McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, p. 152.

- ↑ Howard Lamar, editor. The Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West, (1977). Harper & Row, New York, p. 633.

- ↑ Walton Bean, California: An Interpretive History, Second Ed., McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, p. 159.

- ↑ "History of Transport and Travel". History World. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ↑ Hoffman, Lola B.; California Beginnings; California State Department of Education; 1948; p. 195

- ↑ Eric Foner. "13: Fruits of Manifest Destiny". Give Me Liberty! An American History.(registration required)

- 1 2 3 "Seventy-five Years in San Francisco: Appendix N. Record of Ships Arriving at California Ports from 1774 to 1847". San Francisco History. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ↑ Howard Lamar, editor. The Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West, (1977). Harper & Row, New York, p. 149.

- ↑ "Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Henry Dana". Retrieved May 10, 2012.

- ↑ Federal Income 1850 Federal State Local Government Revenue in United States 2011 – Charts Tables Accessed April 2, 2011

- ↑ Leffingwell, Randy (2005), California Missions and Presidios: The History & Beauty of the Spanish Missions. Voyageur Press, Inc., Stillwater, Minnesota. ISBN 0-89658-492-5, p. 17

- ↑ California State Parks: Custom House

- ↑ Library of Congress. About This Newspaper: The Californian. Retrieved on July 28, 2009.

- ↑ "The Census of 1790, California", California Spanish Genealogy. Retrieved on 2008-08-04. Compiled from William Marvin Mason, The Census of 1790: A Demographic History of California, Menlo Park: Ballena Press, 1998, pp. 75–105. Information in parentheses () is from church records.

- ↑ Rios-Bustamante, Antonio. Mexican Los Ángeles, 43.

- ↑ secularization laws accessed July 7, 2011

- ↑ Hoover, Mildred B.; Hero Rensch; Ethel Rensch; William N. Abeloe (1966). Historic Spots in California. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4482-9.

- ↑ Sonoma Valley Historical Society (1996). The men of the California Bear Flag Revolt and their heritage. Arthur H. Clark Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-87062-261-8.

- ↑ William B. Ide Adobe State Historic Park, California State Parks.

- ↑ Marley, David; Wars of the Americas: a chronology of armed conflict in the New World, 1492 to present [1998); p. 504

- ↑ "Juan Flaco - California's Paul Revere". The Long Riders Guild Academic Foundation. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ↑ Mark J. Denger. "The Mexican War and California: Los Angeles in the War with Mexico". California Center for Military History. Retrieved March 15, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Marley, David; Wars of the Americas: a chronology of armed conflict in the New World, 1492 to present; p. 510

- ↑ Hudson, Tom (1981). "Ch. 4: Massacre in Nigger Canyon". A Thousand Years in Temecula Valley. Temecula, CA: Old Town Temecula Museum. ISBN 978-0931700064. LCCN 81053017. OCLC 8262626. LCC F868.R6 H83 1981.

- ↑ "Campo de Cahuenga, the Birthplace of California". Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ↑ "L.A. Then and Now: Woman Helped Bring a Peaceful End to Mexican-American War". Los Angeles Times. May 5, 2002.

- ↑ Walker, Dale L. (1999). Bear Flag Rising: The Conquest of California, 1846. New York: Macmillan. p. 246. ISBN 0312866852.

- ↑ Walker p. 246

- ↑ Meares, Hadley (July 11, 2014). "In a State of Peace and Tranquility: Campo de Cahuenga and the Birth of American California". KCET. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ↑ Robinson, p. 100

- ↑ House Executive Document 46, pp. 1116–1117

- ↑ Article VIII, Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Center For Land Grant Studies.

- ↑ Article X, Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Center For Land Grant Studies.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sánchez, Rosaura (1995). Telling Identities: The Californio testimonios. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 286–290. ISBN 0-8166-2559-X.

- ↑ Umbeck, John (1981). A Theory of Property Rights with Application to the California Gold Rush. The Iowa State University Press. pp. 208–209.

- ↑ "American Experience | The Gold Rush | People & Events | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- 1 2 "Calisphere - California Cultures - 1848-1865: Gold Rush, Statehood, and the Western Movement". www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 Adrianna Thomas, Raymond Arthur Smith, 2009, Latino and Asian Americans in the California Gold Rush, Columbia University Academic Commons,http://hdl.handle.net/10022/AC:P:8417.

- ↑ Mora, Anthony. "Introduction to Latino Studies". Tisch Hall, Ann Arbor. 9-28-2015. Lecture.

- ↑ Ruiz de Burton, Maria Amparo; Rosaura Sánchez and Beatrice Pita (1992). The Squatter and the Don (2nd ed.). Houston: Arte Publico Press

- ↑ Pitt, Decline of the Californios, pp. 83–102

Bibliography

- Beebe, Rose Marie and Robert M. Senkewicz (2001). Lands of Promise and Despair: Chronicles of Early California, 1535–1846. Berkeley: Heyday Books. ISBN 978-1-890771-48-5.

- Beebe, Rose Marie and Robert M. Senkewicz (2006). Testimonios: Early California through the Eyes of Women, 1815–1848. Berkeley: Heyday Books, The Bancroft Library and the University of California.

- Bouvier, Virginia Marie (2001). Women and the Conquest of California, 1542–1840: Codes of Silence. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-2446-4

- Casas, María Raquél (2007). Married to a Daughter of the Land: Spanish-Mexican Women and Interethnic Marriage in California, 1820–1880. Reno: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 978-0-87417-697-1

- Chávez-García, Miroslava (2004). Negotiating Conquest: Gender and Power in California, 1770s to 1880s. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-2378-8

- Gostin, Ted (2001). Southern California Vital Records, Volume 1: Los Angeles County 1850–1859. Los Angeles: Generations Press. ISBN 978-0-9707988-0-0

- Haas, Lisbeth (1995). Conquests and Historical Identities in California, 1769–1936, Berkeley: University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-08380-6

- Heidenreich, Linda (2007). "This Land was Mexican Once": Histories of Resistance from Northern California. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71634-6

- Hugues, Charles (1975). "The decline of the Californios: The Case of San Diego, 1846-1856", The Journal of San Diego History, Summer 1975, Volume 21, Number 3

- Hurtado, Albert L. (1999). Intimate Frontiers : Sex, Gender, and Culture in Old California. Albuquerque : University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-1954-8

- Mason, William Marvin (1998). The Census of 1790: A Demographic History of California, Menlo Park, California: Ballena Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98083-6

- Osio, Antonio Maria; Rose Marie Beebe and Robert M. Senkewicz (1996) The History of Alta California : A Memoir of Mexican California. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-14974-1

- PBS (2006). The Gold Rush. PBS.

- Pitt, Leonard and Ramón A. Guttiérrez (1998). Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish-Speaking Californians, 1846–1890 (New edition), Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21958-8

- Ruiz de Burton, María Amparo; Rosaura Sánchez and Beatrice Pita (2001). Conflicts of Interest: The Letters of María Amparo Ruiz de Burton. Houston: Atre Publico Press. ISBN 978-1-55885-328-7

- Sánchez, Rosaura (1995). Telling Identities: The Californio Testimonios. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-2559-8

- The editors of Time-Life Books (1976). The Spanish West. New York: Time-Life Books.

- Thomas, Adrianna (2009). Latino and Asian Americans in the California Gold Rush. Columbia University Academic Commons.

- Umbeck, John (1977). The California Gold Rush: A Study of Emerging Property Rights. Academic Press, Inc.

External links

Archival collections

- Guide to the Amador, Yorba, López, and Cota families correspondence. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

- Guide to the Orange County Californio Families Portrait Photograph Album. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

Other

- Californios, a People and a Culture, a personal website

- Pitti, José; Antonia Castaneda and Carlos Cortes (1988). "A History of Mexican Americans in California", in Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Office of Historic Preservation.

- A Continent Divided: The U.S.-Mexico War, Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, University of Texas at Arlington