Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness

| Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category Ib (wilderness area) | |

| |

| Location | San Juan County, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Nearest city | Huerfano, New Mexico |

| Coordinates | 36°18′16″N 108°07′05″W / 36.30444°N 108.11806°WCoordinates: 36°18′16″N 108°07′05″W / 36.30444°N 108.11806°W |

| Area | 45,000 acres (18,000 ha) |

| Established | 1984 |

| Governing body | Bureau of Land Management |

The Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness is a 45,000-acre (18,000 ha) wilderness area located in San Juan County in the U.S. state of New Mexico. Established in 1984, the Wilderness is a desolate area of steeply eroded badlands managed by the Bureau of Land Management, with the exception of three parcels of private Navajo land within its boundaries.[1]

Translated from the Navajo word Bistahí, Bisti means "among the adobe formations."[2] De-Na-Zin takes its name from the Navajo words for "cranes." Petroglyphs of cranes have been found south of the Wilderness.[3] It is on the Trails of the Ancients Byway, one of the designated New Mexico Scenic Byways.[4]

The 1977 film Sorcerer, directed by William Friedkin, filmed one climactic scene on location in the Bisti badlands.

Prehistory and Geology

The area that includes the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness was once a riverine delta that lay just to the west of the shore of an ancient sea, the Western Interior Seaway, which covered much of New Mexico 70 million years ago. The motion of water through and around the ancient river built up layers of sediment. Swamps and the occasional pond bordering the stream left behind large buildups of organic material, in the form of what became beds of lignite. At some point, a volcano deposited a large amount of ash, and the river moved the ash from its original locations. As the water slowly receded, prehistoric animals survived on the lush foliage that grew along the many riverbanks. When the water disappeared it left behind a 1,400-foot (430 m) layer of jumbled sandstone, mudstone, shale, and coal that lay undisturbed for fifty million years. Sandstone layers were deposited above the ash and remains of the delta. The ancient sedimentary deposits were uplifted with the rest of the Colorado Plateau, starting about 25 million years ago. Six thousand years ago the last ice age receded, and the waters of the melting glaciers helped expose fossils and petrified wood, and eroded the rock into the hoodoos now visible.[1]

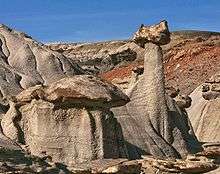

Traveling into the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness today, one descends from tawny sand and sage desert, into a world of gray, black, red and purple sands and rock (see photo above). The Wilderness badlands result from the erosion of the sandy layers of the Ojo Alamo formation, which has left bare the thick deposit of volcanic ash and below that the Fruitland formation and the Kirtland Shale. The western side of the Wilderness, formerly called the Bisti Wilderness, is primarily Fruitland Formation. The eastern side of the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness, formerly called the De-Na-Zin Wilderness, exposes the Kirtland Shale. The ash covers much of these features. When the Wilderness area was still deep underground, water often and easily found its way into the ashy layers. The water left behind deposits of lime that eventually built up and became limestone tubes. As the softer layers wore away, the tubes became exposed. The caps of many of the all-gray hoodoos in the Bisti/De-Na-Zin wilderness are limestone.

Ash erodes very quickly and does not hold water long. These two qualities make for poor growing conditions and explains the general lack of plant life. The lignite beds, left by swamps 70 million years ago, now lie exposed on the broad wash that forms the floor of the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness badlands. Those lignite mounds coincide with most of the petrified wood and fossils found in the Wilderness. Generally, the organic remains are harder than lignite, so they weather out as the lignite erodes.The fossils in the Wilderness preserve a record of freshwater life in and on the edge of the great delta at that time.

Coal was present in the Wilderness, and much of that coal burned in an ancient fire that lasted centuries. The clay over the coal layer was metamorphosed by the heat into red "clinkers" that look today like tiny pottery sherds or perhaps chunks of brick, depending on size. They vary from pale to bright red and can even take on a crimson hue. Their name, "clinker," derives from the characteristic sound these stones make when walked on. The ash, lignite beds and clinkers account for the characteristic gray, black, and red colors of the Wilderness.

On the De-Na-Zin (eastern) side of the Wilderness, the exposed layers of shale coincide with the K/T boundary layer. It is one of the few pieces of public land in the world where the boundary layer is visibly exposed. De-Na-Zin is less ashy and more sandy than Bisti, making for fewer hoodoos and higher hills.

Erosion is the process that shaped the characteristic features of the modern landscape of the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness. The high plains around the Wilderness are about 6,500 feet above sea level today. The badlands lie 200 to 400 feet below those surrounding plains. The highest points in the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness are always grassy. From them, you seem to be looking across a grass plain. This is because all the high points are mesas that stand even with each other, and the clay and lignite surface is hidden as a result of lying below the high points. The impression strengthens one's understanding that everything below the grass has been carved away by wind and water. Anywhere that hard materials sit atop a layer of ash, hoodoos have eroded out of the matrix. While igneous protrusions might be a more common source of stone pillars and pedestals, in the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness, pillars and hoodoos exist solely because everything around and below them has been removed by wind and water, over time.

Humans have occupied the area almost continuously since 10,000 BC. The area contains numerous Chacoan sites and part of the prehistoric Great North Road, used to connect major Chacoan Anasazi sites in the San Juan Basin.[5]

Wildlife

A small variety of wildlife can be found in the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness, including cottontail rabbit, coyote, badger, and prairie dog. Bird species include pinyon jay, raven, quail, dove, ferruginous hawk, prairie falcon, and golden eagle. Lizard, snake, tarantula, and scorpion also live here.[1]

Recreation

Recreational activities in the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness include hiking, camping, wildlife viewing, photography, and horseback riding. Campfires are forbidden in the Wilderness.[1][3]

See also

- Ah-Shi-Sle-Pah Wilderness Study Area

- Chaco Culture National Historical Park

- Đavolja Varoš

- Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument

- Bryce Canyon National Park

- List of U.S. Wilderness Areas

- Wilderness Act

- Demoiselles Coiffées de Pontis

- List of rock formations

- Hoodoo (geology)

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness. |

- 1 2 3 4 Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness - Wilderness.net

- ↑ Young, Robert M. and William Morgan. The Navajo Language. Revised Ed. Univ. of New Mexico Press. Albuquerque: 1987. p.245, column 2.

- 1 2 Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness Archived March 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. - BLM

- ↑ Trail of the Ancients. Archived August 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. New Mexico Tourism Department. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ↑ Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness Archived September 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. - New Mexico Audubon Society

External links

- Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness - Photos, Videos, and Maps

- Bureau of Land Management - official Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness Area website

- Wilderness.net: the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness

- New Mexico Audubon Society - Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness wildlife

- Hanksville.org: Bisti Wilderness

- 'Bisti/De-Na-Zin Hiker: Maps, Geology Guide and Suggested Hikes