Bifidobacterium

| Bifidobacterium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Actinobacteria |

| Class: | Actinobacteria |

| Subclass: | Actinobacteridae |

| Order: | Bifidobacteriales |

| Family: | Bifidobacteriaceae |

| Genus: | Bifidobacterium Orla-Jensen 1924 |

| Species | |

|

B. adolescentis | |

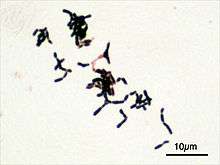

Bifidobacterium is a genus of gram-positive, nonmotile, often branched anaerobic bacteria. They are ubiquitous inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tract, vagina[1][2] and mouth (B. dentium) of mammals, including humans. Bifidobacteria are one of the major genera of bacteria that make up the colon flora in mammals. Some bifidobacteria are used as probiotics.

Before the 1960s, Bifidobacterium species were collectively referred to as "Lactobacillus bifidus".

History

In 1899, Henry Tissier, a French pediatrician at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, isolated a bacterium characterised by a Y-shaped morphology ("bifid") in the intestinal flora of breast-fed infants and named it "bifidus".[3] In 1907, Elie Metchnikoff, deputy director at the Pasteur Institute, propounded the theory that lactic acid bacteria are beneficial to human health.[3] Metchnikoff observed that the longevity of Bulgarian peasants was the result of their consumption of fermented milk products.[4] Elie Metchnikoff also suggested that “oral administration of cultures of fermentative bacteria would implant the beneficial bacteria in the intestinal tract”.[5]

Metabolism

The genus Bifidobacterium possesses a unique fructose-6-phosphate phosphoketolase pathway employed to ferment carbohydrates.

Much metabolic research on bifidobacteria has focused on oligosaccharide metabolism, as these carbohydrates are available in their otherwise nutrient-limited habitats. Infant-associated bifidobacterial phylotypes appear to have evolved the ability to ferment milk oligosaccharides, whereas adult-associated species use plant oligosaccharides, consistent with what they encounter in their respective environments. As breast-fed infants often harbor bifidobacteria-dominated gut consortia, numerous applications attempt to mimic the bifidogenic properties of milk oligosaccharides. These are broadly classified as plant-derived fructo-oligosaccharides or dairy-derived galacto-oligosaccharides, which are differentially metabolized and distinct from milk oligosaccharide catabolism.[2]

Response to oxygen

The sensitivity of members of the genus Bifidobacterium to O2 generally limits probiotic activity to anaerobic habitats. Recent research has reported that some Bifidobacterium strains exhibit various types of oxic growth. Low concentrations of O2 and CO2 can have a stimulatory effect on the growth of these Bifidobacterium strains. Based on the growth profiles under different O2 concentrations, the Bifidobacterium species were classified into four classes: O2-hypersensitive, O2-sensitive, O2-tolerant, and microaerophilic. The primary factor responsible for aerobic growth inhibition is proposed to be the production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the growth medium. A H2O2-forming NADH oxidase was purified from O2-sensitive Bifidobacterium bifidum and was identified as a b-type dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. The kinetic parameters suggested that the enzyme could be involved in H2O2 production in highly aerated environments.[6]

Clinical uses

Bifidobacterim species administered as a probiotic have been found be an effective treatment for some types of inflammatory bowel disease and have no negative side effects.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Schell, Mark A.; Karmirantzou, Maria; Snel, Berend; Vilanova, David; Berger, Bernard; Pessi, Gabriella; Zwahlen, Marie-Camille; Desiere, Frank; et al. (2002). "The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum reflects its adaptation to the human gastrointestinal tract". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (22): 14422–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.212527599. PMC 137899

. PMID 12381787.

. PMID 12381787. - 1 2 Mayo, Baltasar; van Sinderen, Douwe, eds. (2010). Bifidobacteria: Genomics and Molecular Aspects. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-68-4.

- 1 2 "Potential of probiotics as biotherapeutic agents targeting the innate immune system" (PDF). African Journal of Biotechnology. February 2005.

- ↑ "Probiotics: 100 years (1907–2007) after Elie Metchnikoff's Observation" (PDF). Communicating Current Research and Educational Topics and Trends in Applied Microbiology. February 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-04.

- ↑ "Pioneers of Probiotics". European Probiotic Association. February 2012.

- ↑ Sonomoto, Kenji; Yokota, Atsushi, eds. (2011). Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bifidobacteria: Current Progress in Advanced Research. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-82-0.

- ↑ Ghouri, Yezaz A; Richards, David M; Rahimi, Erik F; Krill, Joseph T; Jelinek, Katherine A; DuPont, Andrew W (9 December 2014). "Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics in inflammatory bowel disease". Clin Exp Gastroenterol. pp. 473–487. doi:10.2147/CEG.S27530. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

External links

- Bifidobacterium at Microbe Wiki

- Genomes Online Database contains many Bifidobacterium genome projects

- Comparative Analysis of Bifidobacterium Genomes (at DOE's IMG system)

- Bifidobacterium at BacDive - the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase

| Wikispecies has information related to: Bifidobacterium |