Bathhouse Row

|

Bathhouse Row | |

|

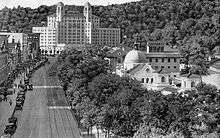

Aerial view of Bathhouse Row | |

| |

| Location | Central Ave. between Reserve and Fountain Sts., in Hot Springs National Park, Hot Springs, Arkansas |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°30′49″N 93°3′13″W / 34.51361°N 93.05361°WCoordinates: 34°30′49″N 93°3′13″W / 34.51361°N 93.05361°W |

| Area | 6 acres (2.4 ha) |

| Built | 1892+ |

| Architect | several |

| Architectural style | several |

| NRHP Reference # | 74000275 [1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 13, 1974[1] |

| Designated NHLD | May 28, 1987 |

Bathhouse Row is a collection of bathhouses, associated buildings, and gardens located at Hot Springs National Park in the city of Hot Springs, Arkansas. The bathhouses were included in 1832 when the Federal Government took over four parcels of land to preserve 47 natural hot springs, their mineral waters which lack the sulphur odor of most hot springs, and their area of origin on the lower slopes of Hot Springs Mountain.[2]

The existing bathhouses are the third and fourth generations of bathhouses along Hot Springs Creek and some sit directly over the hot springs – the resource for which the area was set aside as the first federal reserve in 1832. The bathhouses are a collection of turn-of-the-century eclectic buildings in neoclassical, renaissance-revival, Spanish and Italianate styles aligned in a linear pattern with formal entrances, outdoor fountains, promenades and other landscape-architectural features. The buildings are illustrative of the popularity of the spa movement in the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries.[3] The bathhouse industry went into a steep decline during the mid-20th century as advancements in medicine made bathing in natural hot springs appear less believable as a remedy for illness.[4]

Bathhouse Row was designated a National Historic Landmark on May 28, 1987.[5][6]

Description

The Bathhouse Row contains eight bathhouses aligned in a row: Buckstaff, Fordyce, Hale, Lamar, Maurice, Ozark, Quapaw, and Superior. These were independent, competing, commercial enterprises. The area included in the National Historic Landmark also includes a Grand Promenade on the hill above the bathhouses, an entrance way including fountains, and a National Park Service Administration building.

Buckstaff

Completed in 1912, the elegantly designed Buckstaff Baths operates under National Park Service regulations, its well-trained staff provides a range of services from tradition thermal mineral baths and body massages to Swedish style full body massages. The bathing tubs are private and bathing suits are optional, although visitors may cover themselves between the bathing stations.[7] Services begin with a "Whirlpool Mineral Bath" for $35.00[8]

The cream-colored brick building is neoclassical in style with the base, spandrels, friezes, cornices and the parapet finished in white stucco. It was a radical departure from the fanciful structures that preceded it, and compared to the Irish House of Parliament or the Treasury Building.[9] The entrance is divided into seven bays by engaged columns, with a pavilion on each end.[3]

Friezes above the two-story doric columns have medallions (paterae) that frame the brass lettered words "Buckstaff Baths" centered above the entrance. Brass handrails border the ramp that leads up to the brass-covered and glazed wood-frame entrance doors. First floor windows are arched; second story windows are rectangular. Those on the third floor are small rectangular windows, with classical urns between them above the cornice that finish the columns. The first floor of the building contains the lobby and men's facilities. Women's facilities are on the second floor. The third floor is a common space containing reading and writing rooms and access to the roof-top sun porches at the north and south ends of the building.[3]

Fordyce (now visitor center)

The Fordyce bathhouse is the most elaborate and was the most expensive of the bathhouses, the cost including fixtures and furniture being $212,749.55 US. It was closed on June 29, 1962, the first of the Row establishments to fall victim to the decline in popularity of therapeutic bathing.[4][10] Fordyce Bathhouse has served as the park visitor center since 1989.

The Fordyce bathhouse was built in 1914–15, designed by George Mann and Eugene John Stern of Little Rock, Arkansas. Its surpassing elegance was intentional, as Samuel Fordyce waited to observe the Maurice's construction to find out if he could build "a more attractive and convenient" facility.[11] It was built as a testimonial to the healing waters to which Mr. Fordyce believed he owed his life. It represents the "Golden Age of Bathing" in America, the pinnacle of the American bathing industry's efforts to create a spa rivaling those of Europe. The Fordyce offered all the treatments available in other houses.[10]

The Fordyce provided for the well-being of the whole patron – body, mind, and spirit. It offered a museum where prehistoric Indian relics were displayed, bowling lanes and a billiard room for recreation, a gymnasium for exercise, a roof garden for clean air and sun, and a variety of assembly rooms and staterooms for conversation and reading.[10]

In style, the building is primarily a Renaissance Revival structure, with both Spanish and Italian elements. The building is a three-story structure of brick construction, with a decorative cream-colored brick facing with terra cotta detailing. The foundation and porch are constructed of Batesville limestone. On the upper two stories, the brickwork is patterned in a lozenge design. The first floor exterior of the front elevation to the west is finished with rusticated terra cotta (shaped to look like ashlar stone masonry). The remainder of the first floor is finished with glazed brick. A marquee of stained glass and copper with a parapet of Greek design motifs overhangs the open entrance porch. The north and south end walls have curvilinear parapets of Spanish extraction. These side walls have highly decorative terra cotta windows on the first floor. On the front elevation, the fenestration defines the seven bays of the structure and provides the architectural hierarchy typical of Renaissance Revival–style buildings. The windows on the first floor are of simple rectangular design. Those on the second floor are paired six-light casements within an elaborate terra cotta molding that continues up around the arched window/door openings of the third floor. The arches of those openings are incorporated into the terra cotta frieze that elegantly finishes the top of the wall directly below the cornice. Visible portions of the roof are hipped, covered with decorative tile. Hidden portions of the roof are flat, with the exception of the large skylights constructed of metal frames and wire glass.

The first floor contains the marble-walled lobby, flanked by terra cotta fountains, which has stained glass clerestory windows and ceramic tile flooring. In the vicinity of the lobby desk are a check room, attendant dispatch room, and elevators. The north and central portions of the building house the men's facilities: cooling room, pack room, steam room, hydrotherapy room, and bath hall. The women's facilities, considerably smaller in size, are at the south end of the building. Originally there was a 30 tub capacity. Although the men's and women's bath halls both have stained glass windows in aquatic motifs, the most impressive stained glass is the massive skylight in the men's area, with the DeSoto fountain centered on the floor directly below it. The second floor originally had dressing rooms, lockers, cooling rooms, and massage and mechano-therapy departments; now it is largely occupied by wood changing stalls, with entry to a centrally located quarry-tile courtyard for sunbathing.[10] The third floor houses a massive ceramic-tiled Hubbard Currence therapeutic tub (a full body immersion whirlpool installed in 1938 when other hydrotherapeutic pools were also added), areas for men' s and women' s parlors, and a wood panelled gymnasium to the rear. The most impressive space on the third floor is the assembly room (now museum) where the segmentally arched vaults of the ceiling are filled in with arched, stained glass skylights. Arched wood-frame doors surrounded by fanlights and sidelights open out to the small balconies of the front elevation. The basement houses various mechanical equipment, a bowling alley (since removed), and the Fordyce spring – a glazed tile room with an arched ceiling and a plate glass window covering over the natural hot spring (spring number 46).[3]

Colonel Samuel W. Fordyce was an important figure in the history of Hot Springs – soldier, entrepreneur, and community leader. After experiencing the curative powers of the thermal waters in treating a Civil War injury, he moved to Hot Springs and was involved in numerous businesses including the Arlington and Eastman Hotels, several bathhouses, a theater, the horsecar line, and utilities. Fordyce had a hand in virtually every development which shaped the community and Bathhouse Row from the 1870s to the 1920s.[10]

Hale

The Hale was constructed in 1892–93, replacing an earlier Hale bathhouse. The Hale was probably the first of the Hot Springs 19th-century bathhouses to offer modern conveniences to its bathers, and thus became more cosmopolitan in nature. The first Hale Bathhouse, built in 1841 by John C. Hale, was the first to provide more than just a bath as a service. Within twenty years there were at least three establishments in Hot Springs bearing Hale's name, although none of these appear to have been situated at the location of the present Hale. It is very likely that all the early structures were destroyed by raiders during the Civil War. Following the war, Hale rebuilt his bathhouse near the Alum Spring. John Hale died in 1875 and the bathhouse lease was sold or transferred by his heirs. After the Hot Springs Commission settled land claims in the area in 1879, William Nelson built a bathhouse adjacent to the existing Hale Bathhouse with the intent to replace it. The 1879 frame structure was razed in 1891 and a new building put up on the site the next year by principal owner Colonel Root.[12] The building retains a considerable amount of its 19th-century character and probably has extensive historical archeological potential around its foundation.[3]

Over the entrance there is a double curved parapet with the name of the bathhouse. On either side of the entrance are small windows barred by handsome wrought-iron grilles. The entrance arcade forms a wide sun room where guests could relax. An attractive great-hipped roof of red tile crowns the building on all four sides.[12]

The first floor contains the sun porch, lobby, office, and men's and women's facilities. The south side of the building (the front half and the back two-thirds) contains the men's area with dressing room, pack room, cooling room, and bathing hall with skylight. The women's side contains similar facilities, but smaller in scale. The second floor, reached by stairs flanking either side of the lobby, has additional dressing spaces, cooling rooms, and massage rooms for men and women. The partial basement has employee dressing rooms and a display spring. The basement underwent repairs following a flood in 1956.

The floors were laid with handsome French tiling and/or marble. The bathing department had tile floors, 26 tubs, marble partitions, and nickel-plated hardware. The tubs were rolled, rimmed, and porcelain lined. The 20-foot (6.1 m)-high ceilings provided excellent ventilation. The Hale had two needle and shower baths, one hot room, six cooling rooms, a gymnasium, and 14 dressing rooms on the men's side; the women's department contained 8 tubs, one vapor bath, one hot room, two cooling rooms, one needle bath, and six individual dressing rooms. The house included a subterranean excavation or cave in the tufa bluff directly to the rear of the building. This cave was used as a sweat room; it was known for some time as the "electric cave" until it was closed in 1911.[12]

The building ceased operation as a bathhouse in 1978 and was closed for several years. In 1981 it was remodeled for use as a theater and concessionaire operation (snack bar, gift shops, and arcade). A new emergency exit was installed at the south end of the lobby to meet fire code regulations. The concessionaire operation failed and the building closed nine months later.

The 12,000-square-foot (1,100 m2) building is primarily a brick and concrete structure, reinforced with iron and steel. It was originally built in 1883 in the Classical Revival style, with an enormous central cupola and possessed a flamboyant Victorian air.[9][12] Regulations were changed in 1910 and following negotiations the building underwent extensive renovations in 1914 (design by George Mann and Eugene Stern of Little Rock). It was again remodeled in the late 1930s (design by Thompson, Sanders, and Ginocchio of Little Rock). The latter renovation changed the facade from neo-Classical revival to Mission Style in 1939–40. The building is generally rectangular in plan, and is two and one half stories in height.

By 1919, the neo-Classical building had a hierarchy of fenestration typical of that style: rectangular windows on the ground floor with arched windows on the second floor. The 1939 remodeling included changing the rectangular window openings of the sun porch at the front of the structure to arched window openings, like those on the second story, suggesting arcades of piers with capitals.[12] The classical segmental arch over the main entrance became a simpler Spanish bell gable. The brick was covered with stucco, and wrought iron grilles were placed over the two windows flanking the entrance. The entire effect became very "California". Interior modifications in conjunction with those remodelings are unknown. An unusual engineering feature in the basement is the use of brick vaulting as the form into which concrete was poured for the floor above.[3] In other words, the original first floor structure and basement ceiling has steel beams with shallow brick vaults between them, held in place with steel tension bars; the whole assembly is covered with a concrete topping.[12]

Lamar

The Lamar Bathhouse was completed in 1923 in a transitional style often used in clean-lined commercial buildings of the time that were still not totally devoid of elements left over from various classical revivals: symmetry, cornices, and vague pediments articulating the front entrance.

The sun porch leads into the lobby, whose north, south, and east walls are covered with murals of architectural and country scenes. Facilities including cool rooms, pack rooms and bath halls are on this floor, with the men's at the north and the women's at the south. Centered in the building is the stair core that receives natural light from a skylight above. The second floor contains massage rooms, a writing room, dressing rooms, and a gymnasium. The partial basement houses attendant rooms and mechanical equipment. The building's bathhouse operations ended in November 1985.

The building is a two-story reinforced concrete structure finished with stucco on the exterior. A one-story enclosed sun porch spans nearly the entire length of the front elevation. The two-story portion is rectangular in plan. The flat roof is finished with built-up roofing material, with the exception of the metal-framed wire glass skylight. Brick and clay tiles cap the parapet edges.

The Lamar is now used as the park's giftshop.[3]

Maurice

Construction began on the new Maurice Bathhouse in 1911 and was completed by 1912. The building was designed by George Gleim, Jr. of Chicago. The building was remodeled in 1915, following a design by George Mann and Eugene John Stern of Little Rock, which added the front sun parlor and made the white hygienic appearance warmer and more luxurious.[13]

The exterior of the Maurice Bathhouse is simple yet elegant in design. The interior of the Maurice – patterned after the most successful contemporary European spas – was one of the best equipped and luxurious early-20th-century American bathhouses. The Maurice is probably the best example on Bathhouse Row of a bathhouse specially designed using concrete, metal, and ceramic elements to furnish a hygienic atmosphere and specially equipped with the ultimate in early-20th-century bathing technology. Technologically advanced heating, ventilating, and vacuum-cleaning systems were installed in the Maurice to provide a comfortable, healthy atmosphere for the bather. A therapeutic pool was installed in the Maurice in 1931 to treat various forms of paralysis (spurred on by Franklin Delano Roosevelt's treatments at Warm Springs, Georgia).[3] At this time it was also the first of the Hot Springs bathhouses to provide specialized treatment for polio and other severe muscular and joint problems, being the only one to employ a registered physical therapist.[13]

The first floor has the entrance through the front sun parlor, lobby, stairs and elevators, men's facilities to the south, and women's facilities to the north. The arches and fluted Ionic pilasters of the lobby re-emphasize the elegance presented by the front elevation. An addition to the lobby space is the orange neon "Maurice" sign on the wall behind the marble counter of the front desk. Neon signs were also found on the interior of the Superior and in other businesses in the immediate vicinity. Stained glass skylights and windows of mythical sea scenes in the men's and women's portions contribute to the sophistication of the building. The second floor contains dressing rooms, a billiard room with a mural, and various staff rooms.

The third floor houses the dark-panelled Roycroft Den, named after Elbert Hubbard's New York Press, which promoted the Arts and Crafts movement in the United States. Also known as the "Dutch Den", it replaced a solarium during the 1915 remodeling. The den contains an inglenook fireplace with flanking benches and carved mascarons detail the ends of the ceiling beams. In 1930 the men's basement gymnasium was replaced when the den was converted to a gymnasium; originally there were both men's and women's gymnasiums in the basement.[13]

The building, generally square in plan, is three stories in height and contains 79 rooms and nearly 30,000 square feet (2,800 m2) (including basement). The building was designed in an eclectic combination of Renaissance Revival and Mediterranean styles commonly used by architects in California, such as Julia Morgan. The brick and concrete load-bearing walls are finished with stucco on the exterior, and inset with decorative colored tiles. The front elevation of the building is symmetrical, with a five-bay enclosed sun porch set back between the north- and south-end wings. Besides the symmetry, the hierarchy of fenestration found in Renaissance Revival buildings is also present: delicate arches of the porch window and door openings on the first floor, paired nine-light windows on the second story, and enormous rectangular openings on the third floor, further illuminated by the skylight above. Much of the roof is flat, with parapets and other sections of the roof visible from ground level are covered with green tile. The skylights are metal frames with wire glass. The concrete beams on the interior of the beam and slab floor construction are exposed, finished with plaster similar to the interior walls.

Originally, this building contained 27 tubs (seven of them in the ladies' department), a Nauheim bath, and hydro-therapeutic baths; it could handle 650 bathers a day. Additional tubs were installed in 1924.[13] A Nauheim or effervescent bath is a type of spa bath through which carbon dioxide is bubbled, named after the German spa town.[14] Battle Creek Sanitarium also employed Nauheim baths.[15]

The Maurice represents another facet of American spa history. It provided special services, elegant appointments, and luxurious decor to attract sophisticated bathers who came to Hot Springs to fraternize with their peers. It is said that Jack Dempsey trained in the gymnasium and Elbert Hubbard based one of his Journeys booklets on W. G. Maurice and his bathhouse.[13]

Ozark

The Ozark Bathhouse was completed in 1922 and designed by George Mann and Eugene John Stern of Little Rock. The building closed for use as a bathhouse in 1977.

On the interior, the central lobby has a marble counter with hallways to the men's and women's facilities on either side. Mirrors cover the walls in the lobby. The floor of the sun porch is covered with quarry tile, and most of the remaining floors in the building are finished with acrylic tile. Ceilings are concrete and painted plaster. Interior walls are brick and hollow tile finished with plaster.

The two-story 37-room Spanish Colonial Revival building, approximately 14,000 square feet (1,300 m2), is constructed of brick and concrete masonry finished with stucco. The structure is trapezoidal in plan, although the impressive front elevation is symmetrically designed with twin towers composed of three-tiered setbacks flanking the main entrance. The main entrance is accessed through an enclosed sun porch, a later addition set between two pavilions that form the visual bases of the towers above them. The windows of the pavilions have decorative cartouches above them, as well as a series of rectangular setbacks that evoke a vague Art Deco appearance. Additional wings of the building continue to the north and south of the towers. The sloped roofs over the porch and part of the second story are covered with red clay tile. The hipped roofs of the towers, also covered in red clay tile, are topped with finials. The remainder of the roof is flat, with the exception of the metal-framed glass skylight over the porch.

In 1928 concrete cooling tanks (finished with stucco on the exterior) were added to the rear of the building. The massage rooms were expanded in 1941. The cooling towers were removed in 1953 followed by a complete overhaul of the second story interior in 1956. The skylights were rehabilitated in 1983.[3]

Quapaw

The Quapaw bathhouse was built in 1922 in a Spanish Colonial Revival style building of masonry and reinforced concrete finished with stucco. The most striking exterior feature is the large central dome covered with brilliantly colored tiles and capped with a small copper cupola. The building's use as a bathhouse ended in 1984 when the last contract ended. A new lease was signed with the National Park in 2007 and the Quapaw Bath house reopened as Quapaw Baths & Spa in July 2008.

The Quapaw Bathhouse was built on the sites of two earlier bathhouses, the Horseshoe and the Magnesia, which resulted in its large land assignment on Bathhouse Row. The moderately priced bathhouse services were designed to serve the public at rates set somewhere between the lower-priced Superior and the luxurious Maurice. With an original capacity of 40 tubs the building was expected to handle about three times as many bathers as the Hale or Superior.[16][17]

Originally to be named the Platt Bathhouse, after one of the owners, but when a tufa cavity was discovered during excavation the owners decided to promote it as an Indian cave. It was renamed Quapaw Bathhouse in honor of a local Native American tribe that briefly held the surrounding territory after the Louisiana Purchase was made.[16] The natural hot spring in the building's basement was publicized in promotional brochures making the cave and hot spring a popular attraction. The Quapaw had bathing facilities on its first floor making them accessible to the elderly, handicapped, and wheelchairs.[3]

Most of the floor space is in the U-shaped first floor which has a quarry-tiled lobby with sun porches on each side and massage facilities on the north and south pavilions. The rest of the first floor is divided unequally between the men's and women's bathing facilities which occupy the north and south sides respectively.[18] The narrow rectangular second floor, running the length of the facade and topped with the dome, has dressing rooms and a lounge. The Quapaw was the moderately priced bathhouse with none of the extras such as beauty parlors. Baths, vapors, showers and cooling rooms were provided with massages and some electro-therapy also offered.[16] The partial basement contains a laundry (moved there in the late 1940s), mechanical equipment and a tufa chamber housing the Quapaw spring.

Directly above the entrance is a cartouche with a carved Indian head set into the decorative double-curved parapet. The Indian motif, found in several other places in the bathhouse, was used to reinforce the promotional "Legend of the Quapaw Baths" which claimed that the Indians had discovered the magical healing powers of the cave and spring which were now housed in the building's basement. The double-curved parapets at the north and south ends of the building are capped with scalloped shells that frame spiny sculpin fish. The shell and the fish both emphasize the aquatic aspect of the building. The scalloped shell is a common architectural element found in Spanish Colonial and Revival buildings. Originally the symbol was used to represent Santiago de Campostela, the patron saint of Spain, but it evolved into a mere decorative element in secular revival buildings such as this. The sculpins, originally painted gold, are now painted white.

On the front elevation a series of arched windows is interrupted by a central pavilion that forms the entrance. The arched entrance doorway is flanked by two smaller arches. Further emphasizing the entrance are two large finials that project out of the roofline of the second story, visually framing the dome behind them. The dome's mosaic is chevron-patterned with a band of rectangular and diamond patterns encircling its base. The dome rests on an octagonal base and a new compression ring was installed after 2004.[19] The sloped roofs of the first and second floor are visible from the front elevation and are covered with red clay tiles. Portions of the roof that are not visible from the ground are flat. The interior of the building is more than 20,000 square feet (1,900 m2).

In 1928 the portico across the front of the building was winterized with glass enclosures in the window openings which was removed in the early 21st century. Acoustic tile ceilings were added in the men's first cooling room and the women's pack room. Some of the outside walls were insulated the following year. New partitions were installed in 1944 to allow more space for massage facilities. The display spring in the basement was covered with plate glass in the mid-1950s. Closed in 1968, it was reopened as Health Services, Inc. with only 20 tubs and services that were oriented towards hydrotherapy and physical therapy. It was the only bathhouse open on evenings and weekends. It regained its original name a year before it was closed in 1984 following the discovery of major damage to plaster ceilings and skylights.[18] The exterior was sandblasted, repaired and repainted its original white color in 1976.[3]

Work began in August 2007 to ready the building for its new use with pools added so that whole families can enjoy the spring water together and the bathhouse re-opened to the public in 2008.[19]

Superior

The northernmost bathhouse on the row is the Superior which was completed in 1916 and designed by architect Harry C. Schwebke of Hot Springs, Arkansas. The building is designed in an eclectic commercial style of Classical Revival origin. The building has two stories and a basement, is L-shaped in plan and is constructed of brick masonry and reinforced concrete. It contains 23 rooms and is more than 10,000 square feet (930 m2). The building was constructed on the site of an 1880s Victorian style Superior bathhouse.[3] Brick from the previous bathhouse may have been reused in this structure.[20]

Principal exterior architectural details are on the front elevation. The three bays are separated by brick pilasters with patterned insets and decorated with concrete painted in an imitation of ornamental tiles. Green tile medallions (paterae) are centered over the pilasters in the friezes below the first and second story cornices. Both roofs are flat and topped with brick parapets. The cornice and exterior trim are painted metal and stone.[20]

The one-story sun porch at the front elevation projects out from the main mass of the two-story building. The first floor contains the sun porch, the lobby flanked by the stairs and the bathing facilities. The men's bath hall, dressing rooms and pack room are on the longer north end of the building. The women's facilities are smaller and located on the south side of the building. The two stairways leading upstairs have marble treads and balusters with tile wainscoting on the walls. The second floor is divided down the middle with dressing facilities, cooling rooms and massage rooms on either side for men and women with each served by its own stairs.[20] Bath stalls are marble-walled with tile floors and solid porcelain tubs. The front desk in the lobby is marble while most of the interior hardware is brass. Walls vary from painted plaster to marble (men's hot room) and tile (bath halls). The double hung wood–frame windows have twelve lights over one light. A concrete ramp edged with wrought iron railings provides a central entrance to the structure.

A cooling tank and steel frame to support it were added to the rear of the building in 1920. The building was damaged by a flood in 1923 but the extent of repairs is not known. Some remodeling was completed on the interior in the 1930s, but again the extent of those changes is unknown. In 1957 the massage room was extended, wall radiators were installed, floors were re-tiled and modern lighting fixtures were added. Many of the original furnishings were also replaced at that time. Other changes to the building include the installation of whirlpool equipment in 1962 and air conditioning in 1971. The Superior closed in 1983 and the furnishings were sold at auction.

The Superior currently serves as a brewery and restaurant.

Administration building

Finishing the southern corner of the row is the Administration building which was formerly the National Park Service Visitor Center. Constructed in 1936, this Spanish Colonial Revival building was designed by architects of the Eastern Division, Branch of Plans and Design from the National Park Service. The well-detailed building has a simplified Spanish Baroque doorway framed by pilasters topped with frieze, cornice and finials flanking a second story window. The window has rusticated moldings at its sides and is in turn capped with a broken arched pediment. Windows on the first floor are screened by wrought iron grilles. On the second story there are five–light French doors that open on to wrought iron balconies. The hip roof is covered with clay tile. The air-conditioning system was replaced in 1960. The first floor was remodelled in 1966 to accommodate a lobby and an audio-visual room. Steps up to the front door were enlarged in 1965 and the hand railing may have been put in at that time. The building remains in use as the administrative core of the park.[3]

Other features

Other outdoor features are within the historic district boundaries. The Grand Promenade runs in a north-south direction on the hillside behind the bathhouses, between Reserve Avenue and Fountain Street. Construction on the promenade began in the 1930s and by the beginning of World War II the promenade was a graded pathway covered with gravel. After many false starts due to planning and funding problems the promenade was finally completed in the early 1960s. The paving brick was replaced in 1984.[3]

Fountains for public use have been located in the vicinity since the area was developed and several remain today. The fountain directly in front of the stairway into the administration building is of cast concrete and was built in 1936. A new jug fountain on the sidewalk in front of the administration building was installed in 1966. The Noble fountain at the Reserve Avenue end of the Promenade moved to this location in 1957. The Maurice Spring fountain and retaining wall just north of the Maurice Bathhouse was completed in 1903.[3]

The original main entrance to the reservation was between the Maurice and Fordyce bathhouses directly below the Stevens Balustrade, at about the center of Bathhouse Row. The two bronze federal eagles on their stone pillars still stand guard over the old entrance, forming a gateway to the concrete path that leads between the two bathhouses up to the baroque double staircase of the balustrade. Below the eagles are the names of Secretaries of the Interior Hoke Smith (1893–96) and John Noble (1889–93) and "U.S. Hot Springs Reservation."

The balustrade itself is of limestone ashlar masonry and concrete construction. The central bay houses a vaulted hemicycle niche containing a drinking fountain. The upper portion of the balustrade leads to the Promenade. A bandstand was located along the top of the balustrade on the Promenade, but it was removed because of its deteriorated condition in 1958. By the early 1970s curbs and paving at the old main entrance constructed in the 1890s had been changed and Holly trees were planted to border the entryway. The areas around the bases of the stone pillars, originally paved, were grass-covered by that time.

Several other entrances were located at various points along the linear development of Bathhouse Row during the 1890s but have disappeared over the years as a result of newer construction. None were as elaborate as the Main Entrance which still gives a sense of "high style" to Bathhouse Row. Army engineer Stevens was also responsible for establishing the Magnolia Promenade in front of the bathhouses. The Promenade had double rows of magnolias during the 1890s but now a single row separates the sidewalk and the street. The varied architectural styles of the Bathhouses are pulled together by the linear greenbelts of the Magnolia Promenade and the Grand Promenade and by the smaller hedges and bushes that soften the edges of the spaces between the buildings.[3]

History

Archeological evidence has proven that the hot springs which later supplied the water for Bathhouse Row were used prehistorically for thousands of years. In local Indian mythology the valley of the hot springs was considered neutral ground, a healing place and the sacred territory of the Great Spirit. Close to the springs is a novaculite quarry that was used as a source for material for tools, weapons and household goods. Hernando de Soto may have visited the hot springs in 1541 in his quest for gold, silver and jewels. By 1807 the first permanent white settler was living in the area and shortly after a number of log cabins had been built in the vicinity.

Emergence of formal bathing and health benefits

The first bathhouses were log and wood-frame structures built from 1830 through the 1850s and were used well into the late 19th century.[21] By the mid-19th century the bathing industry in the United States, following elegant European precedents, was establishing more complex bathing rituals. This was influenced by the mid-19th-century promotion of the field of hydrotherapy as a popular medical tool. Newer bathhouses gradually showed influences of Spanish Renaissance architecture.[21]

Government involvement alongside private development

Although the area had been set aside as the first federal reservation in 1832 government acquisition of the lands did not take place until 1879. By that time private development had established its own north–south linear building pattern along the creek and hot springs.[3]

The bathhouses were constructed along the east edge of Hot Springs Creek which was covered over and channeled into a masonry arch in 1884.[3] This eliminated the separate bridges to each bathhouse and also improved sanitation in the area. The space above the arch was filled with dirt and planted, so that each bathhouse now had its own garden space.

From 1892 until 1900 the Department of the Interior undertook a massive beautification project to improve the character of the "National Health Resort". The main landscape thrust of the program was to provide formal gardens in front of the bathhouses and more "natural" landscaped areas behind. The range of landscaping would provide areas for restful walks with enough connection to nature and the outdoors to ensure a healthy atmosphere for recuperation. Frederick Law Olmsted's landscape architectural firm was hired to produce plans for the area but those plans were rejected or left unfinished for a variety of reasons. The project development was given to an Army engineer, Lieutenant Robert Stevens. Stevens designed the entrances to the reservation including the historic main entrance. He also conceived of the Magnolia Promenade in front of the bathhouses, the meandering upper terrace behind the bathhouses, a series of pathways, carriage roads and vest-pocket parks.[3]

Massage services were added in the bathhouses in the late 1890s and later chiropodists.[22]

The Jim Crow period

When Civil War Reconstruction ended in 1877 Jim Crow laws were created which required racial separation of facilities. As this did not formally require separation of workers, African–American workers found that although they could work in the bathhouses, they could not use them for bathing. Although the federal government regulated the bathhouses, local tradition prevailed until segregation ended in the 1960s. During this period African–Americans primarily bathed at bathhouses operated by African–Americans. In the 1880s black patrons could buy bath tickets at the Ozark Bathhouse, the Independent Bathhouse and possibly the Rammelsberg Bathhouse, but they were not allowed to bathe during the hours considered optimum by prescribing physicians, particularly from 10 A.M. to 12 noon. This briefly changed in 1890 when the Independent was purchased by A.C. Page, who operated it as an exclusively black bathhouse for less than a year. William G. Maurice then purchased it, remodeled it and reopened it as the Maurice Bathhouse, an older building than the current Maurice, serving white patrons only. An assortment of buildings and services provided bathing for African–Americans during the period, and until the 1980s most bath attendants were African–Americans.[22]

Away from Bathhouse Row

Facilities were built to serve the Black community — but not along Bathhouse Row until the Crystal Bathhouse opened in 1904. It was located at 415 Malvern Avenue at the edge of the African–American business district. The Crystal burned in the 1913 fire.[22] The Knights of Pythias raised the Pythian on the site of the Crystal Bathhouse in 1914. The Pythian operated successfully until desegregation in 1965 when it began operating part-time until the building finally closed in 1974.[22] The Woodmen of the Union Building opened in 1922. This building included a first-class hotel 2000-seat theater and auditoriam for meetings of up to 600, a gymnasium, a print shop, a beauty parlor and a news–stand. After 1922 black people had two facilities available[22] when the African American National Baptist Convention bought the Woodmen of the Union Building in 1948. In addition to the services offered by the Woodmen, the facility hosted the annual National Baptist Association Convention until the early 1980s. It closed in 1983.[22]

The 20th century

By 1900, the Hot Springs Reservation landscape had both the informal Victorian landscape design and the more formal post-1880s design. A series of bathhouses had been constructed and, through the early decades of the 20th century, the parade of buildings continued. At first, wooden bathhouses were constructed and then replaced after fires or deterioration made them unsafe. Architects began choosing materials less prone to deterioration and fire. The most notable of the period's fires caused destruction of 60 blocks south of the row in 1916 with Central Avenue almost lost as well.[23][24] The changes to the bathhouses over time reflected changes in the bathing industry, changes in technology, and changes in social mores. By the start of the 20th century, Hot Springs became an attraction for fashionable people all over the world to visit and partake of the baths, while maintaining its reputation as a healing place for the sickly.[3] In 1910, the government employed a doctor as medical director of the bathhouses who improved sanitation and bath attendant training.[22] So many establishments were fraudulently soliciting customers that such promotion was barred by the City Council in 1899 although prosecution was necessary for thirty more years.[9][11][25]

In the early 20th century, park superintendent Martin Eisele thought no new bathhouses were needed and the buildings date from that period.[21] It had also been noted that wood buildings rotted due to the high humidity and the structures of this generation of buildings featured concrete, steel and brick.[9]

A few other key points in the history of Bathhouse Row affected the natural and architectural landscape resulting in what remains today. In 1916, Stephen Mather, director of the National Park Service, brought landscape architect Jens Jensen down from Chicago to enhance Bathhouse Row. Under his direction lights were placed along the street promenade and various flower gardens were cultivated in front of the bathhouses. George Mann and Eugene John Stern of Little Rock were hired in 1917 to do a comprehensive plan of Bathhouse Row to guide its future development. In their view a Spanish and Mediterranean Revival architectural theme was appropriate for the "Great American Spa". The intervention of World War I stopped their grand plans although their designs and review of other bathhouse plans had a strong influence on the architectural character of Bathhouse Row. In the 1930s the design of a new hot water system for the bathhouses resulted in changes to curbs, plantings and gutters along the Magnolia Promenade. Although the creek adjoins the bathhouses the bathing and drinking water is piped from several springs and wells.[26] The more formally aligned Grand Promenade at the rear of the bathhouses, begun in the 1930s and completed in the 1960s, replaced the meandering Victorian path and changed the architectural character of area.[3]

The Maurice and Fordyce bathhouses were strategically located at the north and south sides of the historic entrance to the reservation. Both of these buildings provided bathing experiences for the wealthy. The elegant interiors and quality of service attracted an upper class clientele. The placement of the two most architecturally significant structures at the main entrance set the refined architectural character of Bathhouse Row. Both were luxurious in design and were equipped with sophisticated bathing facilities. The Maurice and Fordyce also offered additional attractions: The Fordyce catered to more than the client's physical needs by providing diversions such as a museum displaying prehistoric artifacts, roof gardens, a bowling alley and a gymnasium. The Maurice had its Roycroft Den, or Dutch Den, that served as a gathering place for well-to-do clients.[3] In 1920 the Fordyce and Buckstaff added musicians playing light classical music and popular tunes.[9]

Changes in late 20th century

Facilities in the bathhouses included licensing for the number of tubs along with spraying facilities such as water jets and needle showers. A doctor's prescription was required for some medical services which were provided. Although baths could be taken without the advice of a physician this practice was not recommended. It was advised that baths only be taken for diseases which they could improve along with the proper drugs for the condition.[25] Services included mercury rubs (used since the 16th century for treating syphilis),[22] enemas and massages. The first whirlpool bath was installed in 1937.[11] Mercury treatments began to be replaced by the drug Salvarsan after its invention in 1908 and the clinic above the Government Free Bathhouse began furnishing Salvarsan treatments in 1920.[11] These were finally rendered obsolete by the discovery of penicillin and its widespread manufacture after World War II allowed syphilis to be effectively and reliably cured.

After World War II the bathing industry had large crowds of visitors. In 1946 people took 649,270 hot tub baths establishing a new record. Modern antibiotics developed during the war diminished the use of the thermal waters for medical purposes. Changes in American society prevented many people from taking the long, leisurely vacations that characterized the 19th-century spa life and the automobile allowed Americans to visit more places in a single vacation. During the post-war years visitation to the park increased but visitation to the bathhouses decreased after 1946.[9]

By the 1960s society's needs had changed. The bathhouses became anachronisms as post-Victorian buildings which housed post-Victorian functions. Americans began participating more in various recreational activities and moved away from the social promenading of the spas. Spas that survived this period emphasized a total program of diet, exercise and bathing. Exercise and diet were not adequately addressed by the bathhouse operators in Hot Springs. Bathing practices in Hot Springs became identified with an older generation and few young people took the full course of 21 baths. By 1979 only 96,000 baths were given on Bathhouse Row.[9]

The economics of this labor-intensive industry began to force the bathhouses to close down.[9] The elegant Fordyce Bathhouse was the first to close in 1962 followed by the Maurice, the Ozark and the Hale in the 1970s. In 1984 the Quapaw, briefly reincarnated as Health Services, Inc., and the Superior closed. The Lamar closed in 1985 leaving the Buckstaff as the only bathhouse still operating on Bathhouse Row.[11]

Present

The Buckstaff, Fordyce and Administration buildings are the three buildings presently open to the public. All of the buildings on Bathhouse Row have certain architectural elements in common that contribute to the district's unity:

- All of the buildings are set back the same distance from the sidewalk, and have garden areas and green spaces in front.

- They are all of similar height, scale, and proportions.

- The sidewalk and remaining Magnolia Promenade (there is one row of magnolia trees rather than the original two) to the west and Grand Promenade to the east tie the buildings together.

What makes that unity successful in an architectural sense is the diversity that exists within it. The eclectic combination of styles and materials provides texture and visual interest amongst them. The free use of Greek, Roman, Spanish and Italian architectural idioms emphasize the high style sought after by the planners and create a strong sense of place.[3]

What remains on Bathhouse Row are the architectural remnants of a bygone era when bathing was considered an elegant pastime for the rich and famous and a path to well-being for those with various ailments. Today only the Buckstaff provides baths and related services. Throughout the country 19th-century bathing rituals have been replaced by late-20th-century health spas that emphasize physical fitness and diet though some provide bathing as part of the regimen. The bath is no longer the central feature of rejuvenation provided by spas in the United States. Advances in medicine and the high costs of medical care have diminished the importance of bathing in physical therapy. The need for bathhouses on the scale of Bathhouse Row no longer exists.[3]

Bathhouse Row is the largest collection of 20th-century bathhouses remaining in the United States from the industry's peak from the 1920s through the 1940s. Bathhouse Row is also one of the few collections of historic bathhouses remaining in the United States. As an entity Bathhouse Row represents an area unique to the National Park System as an area where the natural resources historically were harnessed and used rather than preserved in their natural state. On a regional level of significance the bathhouses also form the architectural core of downtown Hot Springs, Arkansas.[3]

Pickup truck enthusiasts have enjoyed the vintage neighborhood during Saturday night cruising among the steaming manholes and free water fountains.[27] Several nonprofit groups have helped with projects such as restoring the Fordyce and Maurice.[28]

According to the National Historic Landmarks Program the status of Bathhouse Row was threatened as most of the historic bathhouses were vacant and are not being maintained. Some have had "damaging uses" contributing to the severe physical deterioration of the majority of the historic bathhouses. Bathhouse Row was added to the National Trust for Historic Preservation list of "11 Most Endangered Places" in 2003. It was removed in May 2007 because the National Park Service began to rehabilitate the buildings.[29] Hot Springs National Park now rents the renovated structures to commercial enterprises who submit an approved request for qualifications. The restoration of Bathhouse Row and commercial leasing of public structures has become a model for similar projects across the country.[30]

Fordyce Bathhouse was restored in 1989 as the park's visitor center and the beginning of restoring all properties on Bathhouse Row.[31][32] The property was closed and renovated between 2012 and 2013, with the Lamar serving as the visitor center in the interim.[33] The Lamar was renovated into offices for park staff and Bathhouse Row Emporium, the park's official store.[34] Ozark Bathhouse was renovated and opened as the Museum of Contemporary Art of Hot Springs in 2009. The museum closed in November 2013, and the NPS is currently receiving proposals for new occupants.[35] Superior and Hale bathhouses went under contract in 2012 following renovation with Vapor Valley Spirits Inc. and Muses Creative Artistry Project, respectively. As of 2014, Superior Bathhouse Brewery and Distillery continues to operate, but the Hale is again available for rent.[36] Buckstaff Bathhouse has been in continuous operation since 1912, and thus is one of the best-preserved structures on Bathhouse Row.[37] The Buckstaff Bathhouse Company has completed the majority of maintenance and renovation that has occurred without outside funding.[1] The Quapaw was restored by the NPS in 2004, and the renovated structure was leased to Quapaw Baths, LLC, who now operates a modern spa with pools and hot tubs.[38] As of February 2014, the Maurice, Ozark and Hale bathhouses are all available for rent from the NPS.[35]

See also

-

Arkansas portal

Arkansas portal -

NRHP portal

- Arlington Hotel near the north end of Bathhouse Row.

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Garland County, Arkansas

References

- 1 2 3 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Buckstaff Bath House – Waters – Spa". www.buckstaffbaths.com. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Harrison, Laura Soullière (November 1986). "Bathhouse Row". Architecture in the Parks. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- 1 2 "FORDYCE Bathhouse General History". asms.k12.ar.us. Archived from the original on 2008-02-28. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ "Bathhouse Row". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-25. Archived from the original on 2008-02-27.

- ↑ Laura Soullière Harrison (1985). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park" (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying 20 photos, exterior and interior, from 1985. (2.95 MB)

- ↑ "Buckstaff Bath House". www.buckstaffbaths.com. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ "Buckstaff Bath Services". Buckstaff Baths. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Paige, John C; Laura Woulliere Harrison (1987). Out of the Vapors: A Social and Architectural History of Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park (PDF). U.S. Department of the Interior.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bathhouse Row Adaptive Use Program / The Fordyce Bathhouse: Technical Report 5. National Park Service. June 1985.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Shugart, Sharon (2004). "The HOT SPRINGS of ARKANSAS THROUGH THE YEARS: A CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS -Excerpts-" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bathhouse Row Adaptive Use Program / The Hale Bathhouse: Technical Report 3. National Park Service. June 1985.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bathhouse Row Adaptive Use Program / The Maurice Bathhouse: Technical Report 4. National Park Service. June 1985.

- ↑ Glanze, W.D., Anderson, K.N., & Anderson, L.E, eds. (1990). Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary (3rd ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: The C.V. Mosby Co. ISBN 0-8016-3227-7. p.797

- ↑ Kellogg, J.H., M.D., Superintendent (1908). The Battle Creek Sanitarium System. History, Organisation, Methods. Michigan: Battle Creek. pp. 79,81,83,170,175,187. Retrieved 2009-10-30. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

- 1 2 3 "Quapaw Bathhouse" (PDF). National Park Service. 2007-08-14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ Shugart, Sharon. "The Legend of the Quapaw Cave, Reexamined" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- 1 2 Bathhouse Row Adaptive Use Program / The Quapaw Bathhouse: Technical Report 6. National Park Service. June 1985.

- 1 2 "Return of the Quapaw Bathhouse". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- 1 2 3 Bathhouse Row Adaptive Use Program / The Superior Bathhouse: Technical Report 2. National Park Service. June 1985.

- 1 2 3 "NPS - Bathhouses of Hot Springs 913-06.pdf" (PDF). National Park Service. 2006-09-13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "African Americans and the Hot Springs Baths" (PDF). Touring Hot Springs National Park with your Class. National Park Service. 2006-08-03. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ↑ "Hot Springs Again Hit by Fire". The Arkansas News. Old State House Museum. Fall 1984. Archived from the original on November 2, 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ↑ "$6,000,000 DAMAGE IN HOT SPRINGS FIRE; Thirty Blocks of Arkansas Resort Swept Away Within a Few Hours.". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. 1913-09-06. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- 1 2 National Park Service (1929). Circular of General Information Regarding Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Bedinger, M. S.; F. J. Pearson, Jr.; J. E. Reed; R. T Sniegocki; C. G. Stone (1979). The Waters of Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas – Their Nature and Origin (PDF). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. C2–C5.

- ↑ Cross, Robert (2002-12-15). "Back to Bathhouse Row". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ↑ "Friends of the Fordyce". Archived from the original on 2007-07-21. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ↑ "Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park". 11 Most Endangered Places. National Trust for Historic Preservation. May 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-07-14. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ↑ Shabecoff, Philip (April 21, 1985). "Revival of Hot Springs Awaits Budget Decision". The New York Times. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Fordyce Bathhouse". National Park Service. March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ Clarke, Jay (October 18, 1987). "Hot Springs On Comeback Trail As Renovation Begins On Bathhouses". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ Adams, Earl; Norman, Bill (December 18, 2013). "Bathhouse Row". Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies and Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Lamar Bathhouse". National Park Service. March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- 1 2 "National Park Service offers Ozark Bathhouse for lease opportunity; new deadline to submit proposal is February. 27". Hot Springs Daily. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Vapor Valley signs lease with National Park Service". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. March 8, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Buckstaff Bathhouse". National Park Service. March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Return of the Quapaw Bathhouse". National Park Service. March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bathhouse Row. |

- Architecture in the Parks: A National Historic Landmark Theme Study: Bathhouse Row, by Laura Soullière Harrison, 1986, at National Park Service.

- Buckstaff Bath House

- Quapaw Baths & Spa

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.