Automotive industry in the Soviet Union

The automotive industry in the Soviet Union spanned the history of the state from 1929 to 1991. It started with the establishment of large car manufacturing plants and reorganisation of the AMO Factory in Moscow in the late 1920s–early 1930s, during the first five-year plan, and continued until the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991. Before its disintegration, the Soviet Union produced 2.1-2.3 million units per year of all types, and was the sixth (previously fifth) largest automotive producer, ranking ninth place in cars, third in trucks, and first in buses.

History

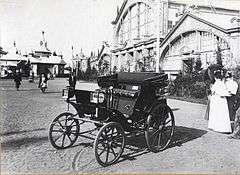

The Russian Empire had a long history of progress in the development of machinery. As early as in the eighteenth century Ivan I. Polzunov constructed the first two-cylinder steam engine in the world,[1] while Ivan P. Kulibin created a human-powered vehicle that had a flywheel, a brake, a gearbox, and roller bearings.[2] One of the world's first tracked vehicles was invented by Fyodor A. Blinov in 1877.[3] In 1896, the Yakovlev engine factory and the Freze carriage-manufacturing workshop manufactured the first Russian petrol-engine automobile, the Yakovlev & Freze.[4] The turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was marked by the invention of the earliest Russian electrocar, nicknamed the “Cuckoo”, which was created by the engineer Hippolyte V. Romanov in 1899. Romanov also constructed a battery-electric omnibus.[5] In the years preceding the 1917 October Revolution, Russia produced a growing number of Russo-Balt, Puzyryov, Lessner, and other vehicles, held its first motor show in 1907[6] and had car enthusiasts who successfully participated in international motor racing. A Russo-Balt car placed 9th in the Monte Carlo Rally of 1912, despite the extreme winter conditions that threatened the lives of the driver and riding mechanic on their way from Saint Petersburg,[7] 2nd in the San Sebastián Rally and covered more than 15,000 km in Western Europe and Northern Africa in 1913. The driver of the car, Andrei P. Nagel, was personally awarded by Emperor Nicholas II for increasing the prestige of the domestic car brand.[8] In 1916, as part of the government program of building six large automobile manufacturing plants, the Trading House Kuznetsov, Ryabushinsky & Co. established AMO (later renamed to First State Automobile Factory, ZIS, and ZIL), but none of the plants were finished due to the political and economic collapse that followed in 1917.

After the 1917 October Revolution, Russo-Balt was nationalised on August 15, 1918, and renamed to Prombron by the new leadership. It continued the production of Russo-Balt cars and launched a new model on October 8, 1922, while AMO built FIAT 15 Ter trucks under licence and released a more modern FIAT-derived truck developed by a team of AMO designers, the AMO-F-15. About 6,000–6,500 F-15s were built in the years 1924–1931.[9][10] In 1927, engineers from the Scientific Automobile & Motor Institute (NAMI) created the first original Soviet car NAMI-I, which was produced in small numbers by the Spartak State Automobile Factory in Moscow, between 1927 and 1931.[11] In 1929, due to a rapidly growing demand for automobiles and in cooperation with its trade partner, the Ford Motor Company, the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy established GAZ.[12][13] A year later, a second automobile plant was founded in Moscow, which would become a major Soviet car maker after World War II and earn nationwide fame under the name Moskvitch. However, due to specific government aims and economic hardships of that time, cars were only a small share of all vehicles produced in the early years of Soviet production.

At the beginning of the 1960s, when MZMA, GAZ and ZAZ were offering a variety of cars and the popularity of having a personal automobile in the Soviet Union was on the rise, the Soviet government opted to build an even larger car manufacturing plant that would produce a people's car and help to meet the demand for personal transport.[14] For reasons of cost-efficiency, it was decided to sign a licence agreement with a foreign company and produce the car on the basis of an existing, modern model. Several options were considered, including Volkswagen, Ford, Peugeot, Renault and FIAT. The Fiat 124 was chosen because of its simple and sturdy design, being easy to manufacture and repair. The plant was built in just 4 years (1966–1970) in the small town of Stavropol Volzhsky, which later grew to a population of more than half a million and was renamed Togliatti to commemorate Palmiro Togliatti.[14][15] At the same time, the Izhmash car plant was established in the city of Izhevsk as part of the Izhevsk Mechanical Plant, with the initiative coming from the Minister of Defence[16] and in order to increase the overall production of cars in the Soviet Union. It produced Moskvitchs and Moskvitch-based kombi hatchbacks. KaMAZ, Europe's largest heavy truck plant, was built in Naberezhnye Chelny, while GAZ, ZIL, UralAZ, KrAZ, MAZ, BelAZ, and plants continued to produce other types of trucks.

By the early 1980s, Soviet automobile industry consisted of several main plants, which produced vehicles for various market segments.

The bulk of the automotive industry of the Soviet Union, with annual production approaching 1.8 million units, was located in Russian SFSR. Ukrainian SSR was second, at more than 200,000 units per year, Byelorussian SSR was third at 40,000. Other Soviet republics (SSRs) did not have significant automotive industries. Only the first two republics produced all types of automobiles.

With the exception of ZAZ and LuAZ, which were located in the Ukrainian SSR, all the aforementioned companies were located in the RSFSR. Besides the RSFSR, some truck plants were established in Ukrainian, Byelorussian, Georgian, Armenian, and Kyrghizian SSRs while buses were produced in the Ukrainian, Latvian, Lithuanian, and Tajik republics.

Domestic car production satisfied only 45% of the domestic demand; nevertheless, no import of cars was permitted.[17] There were queues for the purchase of cars and many domestic buyers often had to wait years for a new car. In the 1970s, passenger cars made by VAZ (Lada) and GAZ (Volga) were the most in demand. Volgas were the most prestigious vehicles sold to private buyers, although up to 60% of the production was reserved for state and party institutions. Always popular and available for sale were Moskvitch and Zaporozhets cars, as well as compact four-wheel-drive LuAZ vehicles. All-terrain cars made by UAZ were not available privately, but could be bought decommissioned. Limousine brands Chaika (GAZ factory) and ZIL were not available for the general public. Prior to 1988, private buyers were also not allowed to buy commercial vehicles like minibuses, vans, trucks or buses for personal use. Soviet industry exported 300,000-400,000 cars annually, mainly to Soviet Union satellite countries, but also to Northern America, Central and Western Europe, and Latin America. There were substantial numbers of highway trucks (Volvo, MAN from capitalist countries; LIAZ, Csepel and IFA from socialist countries) in some quantities, construction trucks (Magirus-Deutz, Tatra), delivery trucks (Robur and Avia) and urban, intercity and tourist buses (Ikarus, Karosa) imported as well.

Pre-Soviet automotive manufacturers

Russian Empire

- The First Russian Factory of Kerosene and Gasoline Engines of Evgeny A. Yakovlev and the Freze & Co. carriage factory, built the first Russian car Yakovlev & Freze in May 1896. In 1910, the plant was sold to Russo-Balt.

-

Yakovlev & Freze (1896, the exact number of cars produced is unknown)

- Russo-Balt (1908–1918), renamed to Prombron in 1918, produced four-wheeled cars, trucks, buses, sports cars, and half-track vehicles.

-

Russo-Balt K12/20 (1911–1913)

-

Russo-Balt S24/55 (1912)

-

Russo-Balt S24-40 (1913–1918)

-

Russo-Balt S24/40 Kégresse (1913)

-

Russo-Balt D-24/40 (1913–1918)

Soviet automotive manufacturers

Armenian SSR

-

ErAZ-762 (1967–1996)

-

ErAZ 762VGP, basing upon the RAF-977 minibus

Azerbaijan SSR

Byelorussian SSR

- BelAZ (1948–present) manufactured super-heavy trucks

-

BelAZ-548A (1967–1975)

-

BelAZ-7540 (1990–present)

- MAZ (1944–present) manufactured heavy trucks

-

MAZ-200 (1950–1965)

-

.jpg)

MAZ-500 (1965–1977)

-

.jpg)

MAZ-5549 (1977–1990)

-

MAZ-5551 (1985–present)

-

MAZ-537 (1959–1989)

-

MAZ-7917 (1984–1992)

- MoAZ (1948–present)

- MZKT (1954–present) in Soviet times, was a division of MAZ, a manufacturer of heavy and super-heavy trucks

- Neman (1984–present) from 1990 started limited production of LiAZ-based buses

-

Neman-52012

-

Neman buses

Estonian SSR

- ToARZ

Georgian SSR

- KAZ (1945–present, truck production ceased in the 1990s) produced backbone tractors with a comfortable cabin, but low quality and dynamic characteristics and had gained in the Soviet Union a bad reputation. Were gradually replaced by tractors MAZ and, later, KaMAZ

Kirghiz SSR

- Frunze Auto-assembly Plant

Latvian SSR

- RAF (1949–1998) produced vans and ambulances on their base

-

.jpg)

RAF-251 - GAZ-51-based bus (1955–1958)

-

RAF-08 Spriditis - 8-passenger prototype bus (1957)

-

RAF-10 Festival - GAZ-M20-based 9-11-passenger bus (1957–1959)

-

RAF-977 Latvia (1959)

-

RAF-977 Latvia - GAZ-21-based 10-passenger van (1959–1976)

-

RAF-2203 Latvia - 4x2 van (1976—1997)

Lithuanian SSR

-

.jpg)

KAG-3

-

.jpg)

KAG-3

- VFTS produced rally cars on Lada chassis

-

Lada 2105 VFTS

-

Lada 2108 Eva VFTS

Russian SFSR

-

Kuban G1 series (1967–1993)

-

Kuban G1 series (1967–1993)

- AvtoVAZ (Lada, 1966–present) produced up to 800,000 cars annually;[18] created in cooperation with Fiat, it started with the production of licensed and upgraded variants of the Fiat 124 or Fiat-derived models and later developed cars entirely of its own design, such as the VAZ-2108/2109/21099, the VAZ-2121, and the VAZ-1111.

-

.jpg)

VAZ-2101 Zhiguli (1970–1988)

-

.jpg)

VAZ-2102 Zhiguli (1971–1985)

-

.jpg)

VAZ-2103 (1972–1984)

-

VAZ-2106 (1976–2005)

-

VAZ-2121 Niva (1977–present)

-

.jpg)

VAZ-2105 (1980–2010)

-

VAZ-2104 (1984-2012)

-

.jpg)

VAZ-2107 (1982-2012)

-

_(2).jpg)

VAZ-2108 Sputnik (1984–2003)

-

.jpg)

VAZ-2109 (1987–2004)

-

.jpg)

VAZ-21099 (1990–2004)

-

.jpg)

VAZ-1111 Oka (1987–1994)

- AZLK (Moskvitch, 1929-2001), originally part of GAZ, built durable and easily repairable cars of similar class as VAZ and of its own design (since 1956), but in a significantly smaller numbers (up to 200,000). All of its cars produced between 1946 and 2001 were known under the name Moskvitch.

-

Ford-A produced at Moscow KIM factory (1933–1939)

-

KIM-10-50 (1940–1941)

-

Moskvitch-400/401 (1946–1956)

-

Moskvitch-402 (1956–1958)

-

Moskvitch-410 (1957–1958)

-

Moskvitch-407 (1958–1963)

-

.jpg)

Moskvitch-403 (1962–1965)

-

.jpg)

Moskvitch-408 (1964–1975)

-

Moskvitch-412 (1968–2001)

-

Moskvitch-427 (1967–1976)

-

.jpg)

Moskvitch-2140 (1976–1988)

-

Moskvitch-2137 (1976–1985)

-

Moskvitch-2140SL (1981–1987)

-

_(15805415925).jpg)

Moskvitch-2141 ALEKO (1986–2001)

- BAZ (1958–present) manufactured military superheavy trucks.

- GAZ (Volga, 1932–present) produced light trucks, Volga business-class sedans, which were also used as taxi cabs, and luxury automobiles such as the Chaika for Soviet officials (up to 100,000 cars annually).

-

GAZ-A (1932–1936)

-

GAZ-M1 (1936–1943)

-

GAZ-GL-1 (1938–1940)

-

GAZ-61 (1941)

-

GAZ-64 (1941–1943)

-

GAZ-67 (1943–1953)

-

GAZ-M20 Pobeda (1946–1955)

-

GAZ-M12 ZIM (1950–1960)

-

GAZ-M72 (1955–1958)

-

.jpg)

GAZ-M21 Volga (1956–1970)

-

GAZ-13 Chaika (1959–1981)

-

.jpg)

GAZ-22 Volga (1962–1970)

-

.jpg)

GAZ-24 Volga (1970–1985)

-

.jpg)

GAZ-24-02 (1972–1987

-

GAZ-24-95 (1974)

-

GAZ-14 (1977–1988)

-

GAZ-14-05 Chaika (1982–1988)

-

GAZ-3102 Volga (1982–2010)

-

GAZ-24-10 Volga (1985-1992)

-

GAZ-AA (1932–1948)

-

GAZ-AAA (1936–1943)

-

GAZ-MM (1938–1949)

-

GAZ-51 (1946–1975)

-

GAZ-63 (1948–1968)

-

GAZ-52/-53 (1961–1993)

-

GAZ-66 (1964–1999)

-

GAZ-3307/3309 (1989–present)

-

GT-SM/GAZ-71 (1968–1985)

-

GAZ-34039 (1985–present)

- IzhAvto (1967–present, the assembly plant AvtoVAZ since 2012), another manufacturer of Moskvitch small family cars and pickups often used by delivery services (produced up to 200,000 annually).

-

.jpg)

Izh-Moskvitch-408 (1966–1967)

-

Izh-Moskvitch-412 (1967–1982)

-

Izh-Moskvitch-412M (1982–2001)

-

.jpg)

Izh-2125 Kombi (1973–1982)

-

Izh-21251 Kombi (1982–1997)

-

Izh-2715-01 Pick-up (1982–1997)

-

Izh-2126 Oda (1990–2005)

-

KamAZ-5511 (1977–1990)

-

KamAZ-4310 (1979–present)

- KAvZ (1958–present) produced conventional small buses on the basis of GAZ trucks, used as company vehicles and for passenger transport in the countryside on roads of poor quality.

-

KAvZ-651/663 (1958–1973)

-

KAvZ-685/3270/3271 (1971–1993)

-

KAvZ-3976 (1989–2008)

- KZKT (1950–2011) manufactured superheavy trucks on MAZ chassis

- LiAZ (1937–present) (not to be confused with the Czechoslovak brand trucks LIAZ) manufactured large city buses.

-

LiAZ-158 (1959–1970)

-

LiAZ-677M (1967–1996)

-

LiAZ-5256 (1986–present)

- NefAZ (1972–present) produced KaMAZ vehicles. Since 2000, it also builds large city buses based on KaMAZ chassis.

- PAZ (1932–present) manufactured small buses

-

PAZ-651 (1952–1961)

-

PAZ-672/3201 (1967–1989)

-

PAZ-32053 (1989–present)

- Prombron (1922–1926), which had acquired control over the former Russo-Balt factory in Fili, produced a small number of modernised Russo-Balt S24 cars. Two of them took part in the All-Russian test run of 1923.

- SMZ, later SeAZ (1939–present, car production stopped in 2008), built cyclecars for the disabled. SMZ cars were distributed in the USSR for free or purchased at a large discount through the Soviet Union's social welfare system.

-

S1L/S3L (1952–1956/1956–1958)

-

SZA (1958–1970)

-

S3D (1970–1997)

- UAZ (1941–present) produced light four-wheel-drive vehicles for either military or agricultural use.

-

UAZ-69A (1954–1972)

-

UAZ-450 (1958–1965)

-

UAZ-469/3151 (1971–present)

-

UAZ-452 (1965–present)

- UralAZ (1941–present) manufactured general purpose off-road 6x6 trucks for use in the Soviet Army.

-

UralZiS-5 (1944–1947)

-

UralZiS-355М (1958–1965)

-

Ural-375 (1959–1991)

- ZiL (former ZiS and AMO, 1916–present) built middle trucks, luxury sedans and limousines used as official state cars.

-

ZiS-101 (1936–1941)

-

.jpg)

ZiS-110 (1945–1958, renamed to ZiL-110 in 1956)

-

ZiL-111V converible (1958–1962)

-

ZiL-111G (1962–1967)

-

ZiL-114 (1970–1978)

-

ZiL-117 (1971–1978)

-

ZiL-115/41045 (1978–1985)

-

ZiL-41044 (1981)

-

ZiL-41047 (1985-2002)

-

ZiL-41041 (1986–2000)

-

ZiS-5 (1933–1948)

-

ZiS-150 (1947–1958)

-

ZiS-151 (1947–1957)

-

ZiL-164 (1957–1961)

-

ZiL-157 (1958–1994)

-

ZiL-130 (1962–1994)

-

ZiL-131 (1966–2002)

-

_(2).jpg)

ZiL-49065 Blue Bird (1975–1991)

-

ZiL-4331 (1987–present)

-

ZiS-8 (1934–1941)

-

ZiS-154 (1946–1950)

-

ZiS-155 (1949–1957, renamed to ZiL-155 in 1956)

-

ZiS-127 (1955–1961, renamed to ZiL-127 in 1956)

-

ZiL-158 (1957–1959)

-

ZiL-118/119 (1962–1994)

-

.jpg)

ZiL-29061/PEM-1M (1979–1983)

Tajik SSR

- Сhkalovsk Bus Plant (1960–1995)

Ukrainian SSR

- Chasiv Yar Repair Plant (1958–present)

- KrAZ (1958–present) (truck production of the Yaroslavl Motor Plant at Kremenchuk Harvester Plant) manufactured heavy trucks

-

KrAZ-256B (1965–1995)

-

.jpg)

KrAZ-255 (1967–1994)

-

.jpg)

KrAZ-260 (1979–1993)

- OdAZ (1948–present)

- LAZ (1945–present) produced suburban and intercity buses of middle class.

-

LAZ-695 Lviv (1957–1964)

-

LAZ-695E Lviv (1964–1970)

-

LAZ-695M Lviv (1970–1976)

-

LAZ-697M Tourist (1970–1976)

-

LAZ-695N (1976–2002)

-

LAZ-699R(1978–2002)

-

LAZ-4202 (1978–1993)

- LuAZ (1955–present) produced compact four-wheel-drive vehicles (up to 17,000 annually)

-

LuAZ-967M (1961–1989)

-

.jpg)

LuAZ-969 Volyn (1971–1975)

-

LuAZ-969M Volyn (1979–1996)

- Luhansk Auto Repair Plant (1944–2011)

- Sievierodonetsk Auto Repair Plant (1962–present)

- ZAZ (1923–present) built Zaporozhets and Tavria subcompact budget cars (as many as 150,000 annually)

-

ZAZ-965/965А Zaporozhets (1960–1969)

-

ZAZ-966 Zaporozhets (1967–1971)

-

ZAZ-968 Zaporozhets (1971–1980)

-

ZAZ-968M Zaporozhets (1980–1994)

-

.jpg)

ZAZ-1102 Tavria (1989–1997)

Post-1991

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, automakers of the newly formed Commonwealth of Independent States were integrated into a market economy and immediately hit by a crisis due to the loss of financial support, economic turmoil, criminal activities[19][20][21] and stiffer competition in the domestic market during the 1990s. Some of them, like AvtoVAZ, turned to cooperation with other companies (such as GM-AvtoVAZ) in order to obtain substantial capital investment and overcome the crisis.[22] Few others, like AZLK, became dormant, whereas ZAZ transformed itself into a new company, UkrAVTO.

In 1997, the production of cars in the Russian Federation increased by 13.2 percent in comparison with 1996 and achieved 981 thousands. AvtoVAZ and UAZ extended their output by 8.8 and 52 percent respectively, whereas KamAZ doubled it. The overall truck production in Russia increased by 7 percent, reaching 148 thousands in 1997[23] and 184 thousands in 2000.[24] The overall production of cars rose from about 800,000 in 1993 to more than 1.16 million in 2000,[25] or 965,000[26] (969,235 according to OICA[27]) excluding commercial vehicles.

Despite remaining strong on its home market, Lada had withdrawn from many export markets, namely the European Union member states, by the late 1990s as its model range failed to meet emissions requirements, and sales had been declining for several years, not helped by the facts that all of its models were at least a decade old and the economic crisis of the 1990s did not allow AvtoVAZ to reorganise and launch new models. It had enjoyed a strong presence in the United Kingdom, selling more than 30,000 units a year at its peak in the late 1980s, only to dwindle away to a fraction of that level by 1996. It was still producing the Fiat-derived Riva saloons and estates by this stage after some 30 years, although it had entered the modern hatchback market in the mid 1980s with the Samara, and since the late 1970s had produced the Niva four-wheel drive. It launched a brand new model with all-new bodyshell and a new range of mechanicals in 1995, with the 2110.

In later years Lada is again exported, mainly the all terrain car Niva but also van editions of the Granta are exported to countries like Germany and Sweden.

Post-Soviet automotive manufacturers

Armenia

- ErAZ (1964–2002)

Azerbaijan

- AzSamand (2005–present)

-

AzSamand Aziz

-

AzSamand Soren

-

AzSamand Runna

- Az Universal Motors (2013–present)

- Ganja Auto Plant (1986–present, car production started in 2004)

-

.jpg)

VAZ-1111 Oka

-

UAZ-315195 Hunter

-

MAZ 551605

- Naz Lifan (2010–present)

-

NAZ Lifan 320

-

NAZ Lifan 520i

-

NAZ Lifan 520

-

NAZ Lifan 620

-

NAZ Lifan X60

Belarus

- BelAZ (1948–present)

- BelGee (2013–present)

- Ford Union (1997–2000)

-

Ford Transit (1997-2000)

-

Ford Escort (1997-2000)

-

Ford Express (1997-2000)

- MAZ (1944–present)

- MAZ-MAN (1997–present)

- MZKT (1954–present)

- Neman (1984–present)

- Unison (1997–present)

Georgia

- KAZ (1945–present, truck production ceased in the 1990s)

Kazakhstan

- Asia-Auto (2000–present)

- AgromashHolding (2003–present)

Latvia

- RAF (1949–1998)

Russia

- Alterna (1991–1995)

- Amur (1967-2012; UAMZ: until 2004)

- AvtoKuban (1962–2001)

- Avtospecoborudovanie (Silant, 2010–present)

- Avtotor (1996–present)

- AvtoVAZ (Lada, 1966–present)

-

.jpg)

VAZ-2131 (1993–present)

-

VAZ-21213/21214 (1994–present)

-

VAZ-2110/Lada 110 (1995–2007)

-

VAZ-2329 (1995–present)

-

VAZ-21106 (1996–2008)

-

Marsh-1/BRONTO-1922 (1996–present)

-

VAZ-2115 Samara 2 (1997–2012)

-

VAZ-2123 (1998–2002)

-

.jpg)

VAZ-2111 (1998–2009)

-

VAZ-2120 Nadezhda (1998–2007)

-

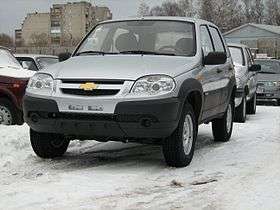

VAZ-21236 Chevrolet Niva (1998–present)

-

VAZ-2112 (1999–2008)

-

VAZ-2114 (2001–2013)

-

VAZ-21123/Lada 112 Coupe (2002–2009)

-

VAZ-1118 Kalina (2004–2013)

-

Chevrolet Viva (2004–2008)

-

VAZ-2170 Priora (2007–present)

-

VAZ-2171 Priora (2009-present)

-

VAZ-2172 Priora (2008–present)

-

VAZ-21728 Priora Coupe (2010–2015)

-

VAZ-2190 Granta (2011–present)

-

Lada Largus (2012–present)

-

Nissan Almera (2012–present)

-

_front.jpg)

VAZ-2192 Kalina II (2013–present)

-

Renault Logan (2013–present)

-

Datsun on-Do (2014–present)

-

Lada Vesta (2015–present)

-

Lada XRAY (2015–present)

-

Moskvitch-2141-02 Svyatogor (1997–2003)

-

GAZ-31029 Volga (1992–1997)

-

GAZ-3110 Volga (1997–2004)

-

GAZ-3111 Volga (1998–2004)

-

GAZ-31105 (2004–2009)

-

Volga Siber (2007–2010)

-

GAZ-322132 Gazelle (1996–present)

-

GAZ-3310 Valday (2003–present)

-

GAZ-2330 Tiger (2005–present)

-

GAZelle Business (2010–present)

-

GAZelle Next (2013–present)

-

GAZon Next (2014–present)

- GolAZ (1990–present, redeveloped in 2014)

- IzhAvto (1967–present, since 2012, the assembly plant AvtoVAZ)

-

Izh-2126 4x4 (1995-2005)

-

Izh-2717 (1997-2005)

-

Izh-21261 Fabula (2003-2005)

-

Izh-27175 (2005-2012)

- KamAZ (1969–present)

-

.jpg)

KamAZ-4326 (1995–present)

-

.jpg)

KamAZ-43114 (1996–present)

-

KamAZ-6560 (2005–present)

-

KamAZ-65117 (2007–present)

-

KamAZ-4308 (2007–present)

-

.jpg)

KamAZ-63968 Typhoon-К (2014–present)

- KAvZ (1958–present)

-

KAvZ-4235 Aurora (2008–present)

-

LiAZ-6212 (2002–present)

-

LiAZ-5292 (2004–present)

-

LiAZ-5280 (2005–2012)

-

LiAZ-5293 (2006–present)

-

LiAZ-6213 (2007–present)

-

LiAZ-6274 (2012)

- Marussia Motors (2007–2014)

-

Marussia B1 (2008)

-

Marussia B2 (2009)

-

Marussia F2 (2010)

-

PAZ-4230 (2001–2002)

-

_17107.jpg)

PAZ-3237 (2002–present)

- RoAZ (2007–2011)

- SeAZ (1939–present, car production stopped in 2008)

- Sollers (2002–present, until 2008 Severstal-Avto)

- TagAZ (1997–2014)

-

TagAZ Vega (2009)

- UAZ (1941–present)

-

UAZ-3159 Bars (1999–present)

-

UAZ-3162 Simbir (2000–2005)

-

.jpg)

UAZ-315195 Hunter (2003–present)

-

.jpg)

UAZ-3163 Patriot (2005–present)

- UralAZ (1941–present)

-

Ural-6368 (2005–present)

-

Ural-532301 (2007–present)

-

Ural-6563 (2008–present)

-

.jpg)

Ural-6370 (2010–present)

-

ZiL-4112R (2006–2012)

-

ZiL-4334 (1994–present)

-

ZiL-5301 Bychok (1996–present)

-

ZiL-5320 (1997–present)

- ZMA (1987–present, since 2005 Sollers-Naberezhnyie Chelny)

Ukraine

- Anto-Rus (2001–present)

- Avtotekhnolohiya (2000–present), based on a private auto repair shop

- Bogdan Corporation (2005–present)

- Bogdan (2005–present)

-

_Lada_110_1.5_Li.jpg)

Bogdan 2110 (2009-2014)

-

Bogdan 2111 (2009-2014)

-

Hyundai Accent MC (2009-2013)

-

Hyundai Elantra XD (2009-2013)

-

Hyundai Tucson JM (2007-2013)

-

JAC J5 (2013–present)

- LuAZ (1955–present, part of the Bogdan Corporation since 2005)

-

LuAZ-1302 Volyn (1992-2002)

-

Bogdan A401.62 (2008–present)

-

Bogdan A092.80 (2010–present)

-

Bogdan A202 (2011–present)

- Etalon-Auto Corporation

- BAZ (2002–present)

- ChAZ (2003–present) based on the bankrupted Chernihiv Auto Part

- Chasiv Yar Repair Plant (1958–present)

- Cherkaskyi Avtobus (1999–present), based on the Cherkasy Auto Repair Plant (1969-1999)

- Dobrota-Auto (2002–present)

- Electron Corporation

- ElectronMash (2013–present)

- ElectronTrans (2013–present)

- Eurocar (2001–present)

- LAZ Holding

- LAZ (1945–present)

-

LAZ-4207 (1990–present)

-

LAZ-5207/LAZ Liner-12 (1994–present)

-

.jpg)

NeoLAZ-12 (2004–present)

-

AeroLAZ (2006–present)

- Dnipro Autobus Plant (2001–present), based on the Dniprodzerzhynsk Auto Repair Plant (1965-2001)

- LARZ (1944-2011)

- KrAZ (1958–present) (truck production of the YaAZ at Kremenchuk Harvester Plant)

-

KrAZ-6443 (1992–present)

-

KrAZ-65055 (1992–present)

-

KrAZ-6322 (1994–present)

-

KrAZ H12.2 (2011–present)

- KrASZ (1995–present) (Science-experimental Mechanical Plant)

- Mykolaiv Machine-building Plant (2004–present), based on the Ship Machine-building Plant (1955-2004) and Project Development Center

- OdAZ (1948–present)

- SARZ (1962–present)

- Stryi-Auto (2005–present) in 2009 absorbed HalAZ (2005-2009)

- ZAZ (1923–present) (until 2001 part of the AvtoZAZ-Daewoo, from 2001 part of UkrAvto)

-

ZAZ-1105 Dana (1994–1997)

-

ZAZ-1103 Slavuta (1998–2011)

-

ZAZ-11055 Tavria Pick-up (1998–2011)

-

Daewoo Lanos/Sens (1998–2005)

-

Daewoo Nubira (1998–2005)

-

Daewoo Leganza (1998–2005)

-

Chevrolet Lacetti (2003-2009)

-

Chevrolet Lanos (2005-2009)

-

ZAZ Sens/Chance/Lanos (2005–present)

-

ZAZ Sens/Lanos Pick-up (2005–present)

-

ZAZ Forza (2010–present)

-

Chevrolet Aveo/ZAZ Vida (2006-2012, 2012–present)

-

ZAZ-A07A I-Van (2005–present)

-

ZAZ-A10C I-Van (2005–present)

Uzbekistan

- GM Uzbekistan (1996–present)

-

_in_russian_winter_(front_view).jpg)

Daewoo Damas (1996–present)

-

Daewoo Tico (1996–present)

-

Daewoo Nexia N100 (1996–2008)

-

Daewoo Matiz M150 (2001–present)

-

Chevrolet Lacetti (2003–2013)

-

Daewoo Nexia II N150 (2008–present)

-

Chevrolet Tacuma (2008–2009)

-

_LS_sedan_(2016-01-07).jpg)

Chevrolet Epica (2008–2011)

-

_01.jpg)

Chevrolet Captiva (2008–present)

-

Chevrolet Spark M300 (2010–present)

-

Chevrolet Cobalt (2012–present)

-

Daewoo Gentra (2013–present)

-

Chevrolet Malibu (2013–present)

-

Chevrolet Orlando (2014–present)

- Land Rover Uzbekistan

- MAN Auto-Uzbekistan (2009–present)

-

MAN TGA Series (2009–present)

-

MAN CLA Series (2010–present)

- SamKochAvto (1996–present)

- UzDaewooAuto (1992–present)

Historical production by year

| Year | Production of vehicles total |

Production of cars |

|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 145,400 | 5,500 |

| 1945 | 74,700 | 5,000 |

| 1947 | 133,000 | 9,600 |

| 1950 | 362,900 | 64,600 |

| 1955 | 445,300 | 107,800 |

| 1958 | 511,100 | 122,200 |

| 1960 | 523,600 | 138,800 |

| 1965 | 616,300 | 201,200 |

| 1970 | 916,000 | 344,300 |

| 1975 | 1,963,900 | 1,201,200 |

| 1980 | 2,199,000 | 1,327,000 |

| 1985 | 2,247,500 | 1,332,300 |

| 1990 | 2,039,600 | 1,260,200 |

See also

- Automotive industry by country

- Economy of the Soviet Union

- List of countries by motor vehicle production

References

- ↑ Hill M. Polzunov`s Engine: Innovation in Eighteenth Century Russia // Icon: Journal of the International Committee for the History of Technology. Volume 8. 2002. P. 127

- ↑ Kelly M. A. Russian Motor Vehicles: The Czarist Period 1784 to 1917. Veloce Publishing Ltd. 2009. P. 8

- ↑ Kelly (2009), p. 12

- ↑ Kelly (2009), p. 50ff

- ↑ Kelly (2009), pp. 71-72

- ↑ (Russian) "Andrei Platonovich Nagel (the organiser of the first Russian auto show)".

- ↑ Scalextric Rally Champions. Vol. I: The interwar period. Altaya. 2008. pp. 20-24.

- ↑ "Melbourne to Moscow".

- ↑ (Russian) "The AMO, known and unknown".

- ↑ (Russian) "Oldtimer picture gallery. The AMO-F-15".

- ↑ Kelly, (2009) p. 78-79

- ↑ "The Ford Motor Company in the Soviet Union in the 1920s-1930s" (PDF).

- ↑ "Soviet Fordism in Practice – Yale University" (PDF).

- 1 2 "AVTOVAZ Joint Stock Company History".

- ↑ (Russian) "The history of Togliatti".

- ↑ (Russian) "The history of the Russian automotive industry: IzhAvto". Za Rulem.

- ↑ Begley, Jason; Collis, Clive; Morris, David. "THE RUSSIAN AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT" (PDF). Applied Research Centre in Sustainable Regeneration.

- ↑ "The Internationalization of the Automobile Industry and Its Effects on the U.S. Automobile Industry: Report on Investigation No. 332-188 Under Section 332 of the Tariff Act of 1930".

- ↑ Ireland A. D., Hoskisson R., Hitt M. Understanding Business Strategy: Concepts and Cases. Cengage Learning. 2005. P. 145

- ↑ Glazunov M. Business in Post-Communist Russia: Privatisation and the Limits of Transformation. Routledge. 2013. Pp. 80-82

- ↑ O’Neal M. Democracy, Civic Culture and Small Business in Russia's Regions: Social Processes in Comparative Historical Perspective. Routledge. 2015. P. 81

- ↑ "AVTOVAZ Joint Stock Company History".

- ↑ "The post-Soviet automobile industry: first signs of revival)" (PDF).

- ↑ (Russian) "Rosstat data".

- ↑ Overview of the Russian Automotive Sector // Kalicki J. H., Lawson E. K. Russian-Eurasian Renaissance? U.S. Trade and Investment in Russia and Eurasia. Stanford University Press. 2003. P. 219

- ↑ (Russian) "Rosstat data".

- ↑ "OICA data".