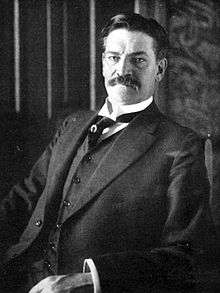

Archibald Gracie IV

| Archibald Gracie IV | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

January 15, 1858 Mobile, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died |

December 4, 1912 (aged 54) New York City, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Complications from diabetes |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx |

| Nationality | American |

| Education |

St. Paul's School United States Military Academy |

| Occupation | Writer, amateur historian, real estate investor |

| Known for | Survivor of the RMS Titanic |

| Parent(s) |

Archibald Gracie III Josephine Archibald |

Colonel Archibald Gracie IV (January 15, 1858 – December 4, 1912) was an American writer, amateur historian, real estate investor, and survivor of the sinking of the RMS Titanic. He was the last survivor to leave the ship and the first adult survivor to die after rescue. He survived the sinking by climbing aboard an overturned collapsible lifeboat and wrote a popular book about the disaster, which is still in print today.[1]

Early life

Gracie was born in Mobile, Alabama, a member of the wealthy Scottish-American Gracie family of New York. He was a namesake and direct descendant of the Archibald Gracie who had built Gracie Mansion, the current official residence of the mayor of New York City, in 1799. His father, Archibald Gracie III, had been an officer with the Washington Light Infantry of the Confederate army during the American Civil War, serving at the Battle of Chickamauga before dying at Petersburg, Virginia, in 1864. Young Archibald attended St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire and the United States Military Academy (though he did not graduate), and eventually became a colonel of the 7th New York Militia. he was married to Constance Elise Schack and had two daughters, Constance Julie (1891-1903), and Edith Temple (1894-1918). in 1903, Constance Julie Gracie was crushed to death in an elevator in the Hôtel de la Trémoïlle in Paris, France and Edith Temple Gracie married, but died not long after in 1918.

Gracie was a keen amateur historian and was especially fascinated by the Battle of Chickamauga, in which his father had served. He spent a number of years collecting facts about the battle and eventually wrote a book called The Truth about Chickamauga. He found the experience rewarding but exhausting; in early 1912 he decided to visit Europe for a brief respite, without his wife Constance (née Schack) and their daughter. He traveled to Europe on RMS Oceanic and eventually decided to return to the United States aboard RMS Titanic. He was a first class passenger.

Aboard the Titanic

Gracie boarded the Titanic at Southampton on April 10, 1912 and was assigned first-class cabin C51. He spent much of the voyage chaperoning various unaccompanied women, including Mrs. Helen Churchill Candee, Mrs. E.D. (Charlotte) Appleton, Mrs. R.C. (Malvina) Cornell, and Mrs. J.M. (Caroline) Brown. He also spent time reading books he had found in the first-class library, socializing with his friend J. Clinch Smith, and discussing the Civil War with Isidor Straus. He was known among the other first-class passengers as a tireless raconteur who had an inexhaustible supply of stories about Chickamauga and the Civil War in general.

On April 14, Gracie decided that he had neglected his health and spent some time in physical exercise on the squash courts and in the ship's swimming pool. He then attended divine services, had an early lunch, and spent the rest of the day reading and socializing. He went to bed early, intending on an early start the next morning on the ship's squash courts.

At about 11:45 pm ship's time Gracie was jarred awake by a jolt. He sat up, realized the ship's engines were no longer moving, and partially dressed, putting on a Norfolk jacket over his regular clothes. Reaching the Boat Deck, he realized the ship was listing slightly. He returned to his cabin to put on his life jacket and on the way back found the women he had been chaperoning. He escorted them up to the Boat Deck and made sure they entered lifeboats. He then retrieved blankets for the women in the boats, and along with his friend Smith assisted Second Officer Charles Lightoller in filling the remaining lifeboats with women and children.

Once the last regular lifeboat had been launched at 1:55 am on the 15th, Gracie and Smith assisted Lightoller and others in freeing the four Engelhardt collapsible boats that were stored atop the crew quarters and attached to the roof by heavy cords and canvas lashings. Gracie had to lend Lightoller his penknife so the boats could be freed. The men were able to launch Collapsibles "C" and "D" and free Collapsible "A" from its lashings, but while they were freeing Collapsible "B" from its place the bridge was suddenly awash. Gracie later wrote about the moment:

My friend Clinch Smith made the proposition that we should leave and go toward the stern. But there arose before us from the decks below a mass of humanity several lines deep converging on the Boat Deck facing us and completely blocking our passage to the stern. There were women in the crowd as well as men and these seemed to be steerage passengers who had just come up from the decks below. Even among these people there was no hysterical cry, no evidence of panic. Oh the agony of it.

As the fore part of the ship dipped below the surface and the water rushed towards them, Gracie jumped with the wave, caught a handhold, and pulled himself up to the roof of the bridge. The undertow caused by the ship's sinking pulled Gracie down; he freed himself from the ship and rose to the surface near the overturned Collapsible "B". Gracie scrambled onto the overturned lifeboat along with a few dozen other men in the water. His friend Clinch Smith disappeared; his remains were never found. In his memoir, Gracie surmises Smith became entangled with the ropes and other debris on the ship, and could not free himself.

As the night wore on, the exhausted, freezing, and soaking wet men aboard the overturned Collapsible "B" found it almost impossible to remain on the slick keel. Gracie later wrote that over half the men who had originally reached the collapsible were claimed by exhaustion or cold and slipped off the upturned keel during the night. As dawn broke and it became possible for those in other lifeboats to see them, Second Officer Lightoller (who was also on the collapsible, along with Wireless Operator Harold Bride) used his officer's whistle to attract the other boats' attention; eventually lifeboats Nos. 4 and 12 rowed over and took the remaining men off the overturned boat. Gracie was so tired that he was unable to make the jump himself and was pulled into lifeboat No. 12, the last to reach RMS Carpathia when that ship, captained by Arthur Henry Rostron, arrived on the scene.

After the rescue

Gracie returned to New York aboard the Carpathia and immediately started on a book about his experiences aboard the Titanic and Collapsible "B". His is one of the most detailed accounts of the events of the evening; Gracie spent months trying to determine exactly who was in each lifeboat and when certain events took place.

His work is not without faults; Gracie referred to every stowaway or man who jumped or sneaked aboard a lifeboat as a(n) "Italian", "Japanese", or "Latin", and only gave the names of the men who put their wives aboard lifeboats and remained on the ship if they had been in first class.

Gracie died before he could finish correcting the proofs of his book. It was published in 1913 under the original title, The Truth about the Titanic.[2] Since then, the book has gone through numerous printings and is currently available under the title Titanic: A Survivor's Story. Most modern editions also include a short account of the disaster by John B. "Jack" Thayer, III, who also survived the sinking aboard Collapsible "B"; Thayer's account, "privately published for his family and friends in 1940", is titled The Sinking of the S.S. Titanic.[3][4]

Health and death

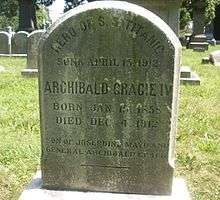

Gracie never recovered from the ordeal; as a diabetic, his health was severely affected by the hypothermia and physical injuries he suffered. He died of complications from diabetes on December 4, 1912, less than eight months after the sinking.[1] He was buried in the Gracie family plot at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City; many of his fellow survivors, as well as family members of victims, attended his funeral. He was the first adult survivor to die.

Gracie was so preoccupied with the Titanic's sinking and work he had done on the subject that his last words were, "We must get them into the boats. We must get them all into the boats."[1]

In popular culture

As one of the best-known survivors of the disaster, Gracie has been featured as a character in many of the dramatizations of the Titanic's sinking. For example, he was played by James Dyrenforth in A Night to Remember (1958) and by Bernard Fox in the film Titanic (1997) - in which he speaks with a rather incongruous British accent despite being American.

Bibliography

- The Truth About the Titanic by Colonel Archibald Gracie, New York, Mitchell Kennerley, 1913

- Titanic: A Survivor's Story and the Sinking of the S.S. Titanic by Archibald Gracie and Jack Thayer, Academy Chicago Publishers, 1988 ISBN 0-89733-452-3

- The Truth about Chickamauga, by Archibald Gracie, 1911 ISBN 0-89029-038-5

References

- 1 2 3 "Col. Gracie Dies, Haunted By Titanic. 'We Must Get Them All in the Boats,' Last Words of the Man Who Helped to Save Many". New York Times. December 5, 1912. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

Col. Archibald Gracie, U. S. A., retired, died yesterday morning at his apartment at the Hotel St. Louis, in East Thirty-second Street. Death was immediately due to a complication of diseases, but the members of his family and his physicians felt that the real cause was the shock he suffered last April when he went down with the ship and was rescued later after long hours on a half-submerged raft. ... Col. Gracie was believed to have been the last survivor of the lost Titanic to leave the ship.

- ↑ Gracie, Archibald IV (2013). The Truth About the Titanic. ISBN 1478164476.

- ↑ Gracie, Archibald IV & Thayer, John B. III. Titanic: A Survivor's Story & The Sinking of the S.S. Titanic. ISBN 978-0753154533.

- ↑ Lord, Walter. The Night Goes On. p. 2 (Chapter X).

Further reading

- Eaton, John P. & Haas, Charles A. (1995). Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy (2nd ed.). W.W. Newton & Company. ISBN 0-393-03697-9.

External links

- "Archibald Gracie Death Certificate". Titanic-Titanic.com.

- "Biography of Archibald Gracie". Encyclopedia Titanica.