Antonio Iturmendi Bañales

| Antonio Iturmendi Bañales | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Antonio Iturmendi Bañales 1903 Baracaldo, Spain |

| Died |

1976 Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | lawyer |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | Comunión Tradicionalista, Falange Española Tradicionalista |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Antonio Iturmendi Bañales (Baracaldo, 1903 – Madrid, 1976) was a Spanish Carlist and Francoist politician.

Family and Youth

Antonio Iturmendi Bañales was born to a well established, much branched and distinguished Navarrese family originating from Morentin. The brother of his great-grandfather, Emeterio Celedonio Iturmendi Barbarin, became an icon of the Carlist insurgency, taking part in three Carlist wars (1833-8, 1849, 1873-6) and growing to a general under Carlos VII. The Carlist sympathies were shared by the family further on and passed to Antonio's father, José Iturmendi Lopez (1873-1955). Educated in jurisprudence, he settled in the city of Baracaldo and worked as a lawyer for almost half a century. Starting 1920s he represented various local bodies, like Banco Vasco, in negotiations with the central Madrid government. In the mid-1930s he became dean of the Colegio de Abogados of the Biscay province, the position held for 5 years. Married to Julia Bañales Menchaca, the couple had 11 children, 7 sons (José, Antonio, Pedro, Emilio, Marcelo, Jesus and Ramón) and 4 daughters (María Victoria, María Purificación, María de los Angeles and Ana María).

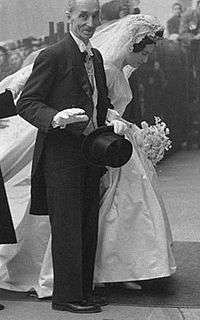

Like his siblings, Antonio was raised in a profoundly Catholic atmosphere; he started education at the Doctrina Cristiana and Sagrados Corazones schools. He entered Universidad de Deusto, the prestigious Bilbao based high school founded by the Jesuit Order, and graduated in law. Having successfully passed the exams he entered Cuerpo de Abogados de Estado as the 2nd in rank. In 1926 he was nominated teniente de alcalde and commenced working for Ayuntamiento de Bilbao. He married Rita Gómez Nales and fathered 4 children: Antonio, María Teresa, Javier and Pilar (Maria Teresa married Alfonso Osorio García, a Francoist and later Christian-Democrat politician, official and businessman). His nephew, José Iturmendi Morales, became a scholar in law at Universidad Complutense in Madrid.

Rise to power

Throughout the late 1920s and the early 1930s Iturmendi gradually grew in the administrative structures of the local Biscay administration, becoming asesor juridico for Gobierno Civil de Vizcaya (at the same time he practiced privately as a lawyer in various locations, e.g. in Logroño and Bilbao). It is during this service that he met Esteban Bilbao, some 25 years his senior, also the Deusto law graduate and former law adviser to the Biscay government. During the Primo de Rivera dictatorship Bilbao served as president of Diputación de Vizcaya, and he worked with Iturmendi when preparing negotiations between the provincial government and Madrid, especially the annual Concierto Economico agreement; he became Iturmendi's political mentor and patron. Following the fall of the monarchy Bilbao commenced conspiring against the Republic; it is not clear whether Iturmendi, member of the new united Carlist organisation, Comunión Tradicionalista, was in any way engaged. None of the studies available mentions him as involved in any Carlist initiative, be it political or otherwise.

It is not clear how Iturmendi spent the first months of the Civil War. In June 1937, when the city of Bilbao fell to the Nationalists and Concierto Economico was scrapped by Franco 4 days later, Iturmendi was nominated one of 3 lawyers to represent the Biscay province in talks with the Burgos based Junta Técnica del Estado. His task was to negotiate the procedure of handing over local provincial duties to the Nationalist quasi-government. Recommended by Bilbao, Iturmendi joined the Francoist administration. In January 1939 he was nominated gobernador civil of Tarragona; at this position he demonstrated utter loyalty to Franco when during the conflict over ecclesiastical nominations he outmaneuvered the papal nominee, Francesc Vives. In March 1939 he moved – again as gobernador civil - to Zaragoza.

Late 1939 Itumendi was nominated head of Dirección General de Administración Local; he co-ordinated works on the draft Código de Gobierno y Administración Local, organised Cuerpo de Funcionarios of the local administration and founded Instituto de Estudios de Administración Local (serving as its vice-president). The post provided him with some influence over local appointments, which he exercised to endorse cautiously Carlists sympathisers like José Vilaplana Pujolar, the mayor of Vic. Though he unconditionally accepted amalgamation into Falange Española Tradicionalista, Iturmendi was not among 11 Carlists appointed to the first Consejo Nacional; his nomination came in 1939. Ceased his functions at Administración Local in 1941; he was moved to Ministry of Interior as its subsecretary working first with Valentín Galarza Morante and then with Blas Pérez González . He carried on with his law practice in Madrid. In the late 1940s, within the Instituto Nacional de Industria governing framework, Iturmendi was granted presidency of Fabricación Española de Fibras Textiles Artificiales (FEFASA), the company built from scratch by INI in Miranda de Ebro.

Minister of justice

In 1951 Iturmendi was nominated Minister of Justice. By that time the regime had already mitigated its terror, with capital punishments and executions becoming an exception rather than a rule; the basic Francoist legislation had already been in place. Iturmendi focused on regulations which stabilised the system further on: finetuning of the Civil Code, Ley de Jurisdicción Contencioso-Administrativa, Ley de Sociedales de Responsabilidad Limitada, Ley de Expropriación Forzosa, Ley de Venta de Bienes and Ley de Adopción (which acknowledged women's family rights). He endorsed the foral tradition of Álava and Navarre (though not this of Biscay and Gipuzkoa), developing legal infrastructure for semi-autonomous governance, a compromise between foralist recommendations of the Congreso Nacional de Derecho Civil in Zaragoza in 1946 and Franco's own preference for centralism and his animosity to the Basque and Catalan aspirations.

In 1956 the syndicalist hardliners produced the last serious attempt to convert the regime into a fully totalitarian system; José Arrese drafted the law which would dramatically increase the powers of Falange. Iturmendi sided with the army, the Church and particularly the monarchists; as a Traditionalist he believed that a monarch should be free to appoint any government he deems proper. He wrote a few notes to Franco arguing against the proposal and stating that "the state should represent all Spaniards, even those not affiliated to the Movement"; he also denounced features resembling Soviet-style regimes like these of the USSR, Poland, Yugoslavia or China. Iturmendi countered Arrese with his own set of legislative proposals, in fact drafted by López Rodó. The climax led to the cabinet reshuffle, sidetracking of Arrese, adoption of a vague Ley de Principios del Movimiento Nacional (1958) and ultimately the power shifting to the technocrats.

Following the notorious 1963 case of Julián Grimau, which exposed inconsistencies in the Francoist penal infrastructure, Iturmendi prepared legislation setting up Juzgado y Tribunal de Orden Publico. In 1965 this tribunal replaced the obsolete Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo; it was designed to handle high-profile political cases and topped the Francoist repressive system. During his tenure as a Minister of Justice Iturmendi was also many times for short periods double-hatting as a caretaker minister for Public Works (1953-1955), Economy (1956–64), Education (1958–60), Labor (1958–59) and Information (1964).

Collaborative Carlist

By accepting a post in the Falangist Consejo Nacional Iturmendi broke loyalty to the Carlist regent-claimant, Don Javier, and was expelled from technically illegal Comunión Tradicionalista, though in August 1943 together with key Carlist leaders he signed a letter to Franco, demanding that totalitarian features of the regime are removed. When Karl Pius Habsburgo-Lorena y Borbón styled himself as Carlos VIII and raised his claim to the throne, Iturmendi declared himself sympathetic and kept endorsing the pretender. The support did not breach the rules of Carlist regency, which theoretically allowed supporting prospective candidates, but in practice it exerted pressure on Don Javier, especially that the carloctavistas appeared to have enjoyed some backing of the regime. The unexpected death of Karl Pius in 1953 left Iturmendi disoriented; he neither joined the Carlists supporting another carloctavista candidate Don Antonio, nor attempted reconciliation with Don Javier. After the death of Tomás Domínguez Arévalo, leader of the juanista faction within Carlism, many former rodeznistas refused to align with intransigency of the formal political leader, Manuel Fal Conde, and to support the claim to the trone raised by Don Javier earlier the same year. Instead, they considered pursuing a collaborative strategy under the leadership of Luis Arellano or Iturmendi himself, possibly maintaining a Carlist regentialist solution. There were also rumours that Franco intended to create a competitive Comunión Tradicionalista, a party to be led by Iturmendi. The resulting confusion left most Carlists in disarray.

In January 1956 Don Javier visited Madrid and made ambiguous declarations in front of the Consejo Nacional de la Comunión, hesitating whether to confirm his claim to the throne, backtrack to regency or seek alignment with the Alfonsinos. As the Minister of Justice Iturmendi visited him and urged that he abandons any dynastical claims; he allegedly threatened Don Javier with shooting. The following day Don Javier retracted, causing profound grief among the Carlist leaders. In the bewilderement that followed some Traditionalists started a campaign against Iturmendi, while the others suggested that Don Javier remains a king "privately", with some sort of agreement to be worked out by Valiente and Iturmendi, their best liaison with Franco.

In the mid-1950s the Carlist leaders concluded that Falangism had crashed and it was time to commence cautious collaboration with the regime. Iturmendi seemed to have been an acceptable partner, especially that he had not joined the estorilos, a large group of former rodeznistas who declared Don Juan the legitimate Carlist pretender. However, in the late 1950s Iturmendi refrained from promoting the javierista cause. When in the early 1960s the javieristas campaigned for Spanish citizenship to be granted to Don Javier's son, Carlos Hugo, Iturmendi - as a Minister of Justice fully entitled to settle the issue - declared himself unable to make a highly political decision and preferred to consult Franco, who decided to the negative. As the Francoist regime seemed geared towards Juan Carlos as the future king, Iturmendi put up with the perspective of the Alfonsist restoration. Though he kept attending Carlist feasts, his Carlism was in fact watered down to conservative Christian monarchism. By the end of his life he joined forces with Traditionalist Carlists when in the early 1970s trying to elevate Hermandad de Maestrazgo, a local Carlist organisation, into a nationwide structure competitive to Comunión Tradicionalista, already controlled by the socialist supporters of Carlos Hugo and being transformed into Partido Carlista.

Cortes Españolas

When the Francoist quasi-parliament Cortes Españolas was established in 1942, Iturmendi was not a member of the Falangist Consejo Nacional (he resigned shortly before in protest against the Begoña incident which he witnessed personally) and did not qualify automatically to the diet. He was re-appointed to the Consejo in 1947 (gradually rising to member of its Comisión Permanente in the 1960s) and by this token entered the III Cortes in 1949. From this moment onwards he remained a procurador during the following 28 years, forming part of all the subsequent Francoist chambers in 1952, 1955, 1958, 1961, 1964, 1967 and 1971; until 1964 he held double eligibility as minister and as consejero nacional. In the legislature he either led or took part in a number of committees, most notably these dedicated to legal issues and to the economy. His career was crowned in 1965, when Esteban Bilbao resigned as president of the Cortes. Franco, who as part of his balancing game reserved the parliament speaker role to the Carlists, appointed Iturmendi, the next Carlista de turno, at that time the most senior of the collaborative Traditionalists.

By virtue of his parliament speaker role, in 1965 Iturmendi entered two bodies established by Ley de Sucesión: Consejo del Reino and Consejo de Regencia. The former, a peculiar diarchic structure for an authoritarian monarchy proposed earlier by Primo de Rivera, was designed as a special deputy to the executive. It was supposed to assist the Head of State on matters falling into his exclusive competence and was presided by Iturmendi himself. The latter, composed of 3 officials, was to act as an interim regency during the transition to Franco’s successor or in his absence. As Presidente de las Cortes Españolas, Presidente del Consejo del Reino and Presidente del Consejo de Regencia Iturmendi enjoyed the most prestigious and distinguished positions available to civilians in the Francoist Spain, though there was very little if any political power attached to any of them (along Esteban Bilbao and Joaquín Bau he was also one of the highest placed Carlists in the regime). In front of Iturmendi Juan Carlos de Borbón swore fidelity to the Francoist leyes fundamentales when nominated the future king of Spain in 1969. In 1969 Iturmendi resigned all presidential functions quoting his age and started withdrawing from politics.

Other

_01.jpg)

Iturmendi was a member of numerous juridical bodies, Real Academia de Jurisprudencia y Legislación having been the most notable of them. In 1955 he was declared hijo predilecto by the city of Baracaldo. Author of works ranging from history of political thought (Balmes sacerdote: Su magisterio político visto por un seglar, En torno a la doctrina de la soberanía social en Vázquez de Mella) to theory of law (De la justicia y de los jueces) to foralism (Las compilaciones forales en el proceso de la codificación española, with Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta) to municipal law (El régimen municipal en los pueblos adoptados) to juridical organisation (Perfeccionamiento de la organización y procedimiento de la justicia). Decorated with Cross of Isabel la Católica, Order of Carlos III, Order of San Raimundo de Peñafort, Mérito Civil, Mérito Agricola, Mérito Naval and other honors. In 1977 king Juan Carlos posthumously conferred upon Iturmendi the title of conde, inherited by his wife and currently held by Antonio Iturmendi Mac-Lellan, III conde de Iturmendi. There is a street commemorating him in Quart de Poblet. His portrait is displayed in the gallery of Cortes speakers, though for some time deputies from La Izquierda Plural have been demanding that it is removed. When his nephew, José Iturmendi Morales, ran for the Universidad Complutense rectorship in 2011, he was denounced by his opponents as heir to Antonio Iturmendi (and lost).

See also

References

- Eduardo J. Alonso Olea, El crédito de la Unión Minera: 1901-2002, [in:] Historia Contemporánea 24, 2002, 323-353

- Álvaro de Diego González, Algunas de las claves de la transición en el punto de inflexión del franquismo la etapa constituyente de Arrese (1956-1957), [in:] La transición a la democracia en España: actas de las VI Jornadas de Castilla-La Mancha sobre Investigación en Archivos, Guadalajara 2004, Vol. 2, ISBN 8493165891

- Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo, 1962-1977, Pamplona 1997; ISBN 9788431315641, 9788431315641

- Martí Marín i Corbera, El personal polític de l'ajuntament de Vic durant el franquisme: algunes consideracions (1939-1975), [in:] AUSA XIX 146 (2001)

- Stanley G. Payne, The Franco Regime, London 1987, ISBN 0299110702, 9780299110741

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil, [PhD thesis], Valencia 2009

- Hilari Raguer, Gunpowder and Incense: The Catholic Church and the Spanish Civil War, Routledge 2007, ISBN 9781134365937

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El nuevo rumbo político del carlismo hacia la colaboración con el régimen (1955–56) [in:] Hispania, Vol 69, No 231 (2009), ISSN 0018-2141

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El papel del carlismo navarro en el inicio de la fragmentación definitiva de la comunión tradicionalista (1957-1960) [in:] Príncipe de Viana (PV), 254 (2011), ISSN 0032-8472

- Aurora Villanueva Martínez, Organización, actividad y bases del carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, [in:] Gerónimo de Uztariz 19 (2003), ISSN 1133-651X

External links

- Iturmendi family and Morentin

- Emeterio Celedonio Iturmendi Barbarin on euskomedia

- Iturmendi's father as consejal de Banco Vasco

- Iturmendi's father obituary

- Iturmendi's father necrology

- Iturmendi's mother obituary

- Iturmendi on euskomedia

- official info on Cortes' site

- entering Colegio de Abogados

- nominated Abogado de Estado

- as Biscay delegate in 1937

- and the conflict with Church in Tarragona

- appointed to Consejo Nacional (1939)

- promoting sympathisers in Vic

- present during Begona incident

- again Begona incident

- appointed to Consejo Nacional (1947)

- FEFASA president

- FEFASA as part of the INI cellulose strategy

- FEFASA

- hijo predilecto of Baracaldo

- threatening Don Javier with execution

- and a Francoist-licensed Comunion Tradicionalista

- and 1956 climax

- 1956 climax again

- sworn as president of Cortes (video)

- Juan Carlos swearing to Iturmendi (video)

- obituary in La Vanguardia

- obituary in ABC

- necrology in ABC

- declared traitor by a hugocarlista historian

- posthumously made conde

- selected bibliography

- Iturmendi's nephew denounced as requete

- Left deputies demanding Iturmendi's portrait is removed

- portrait as in the Cortes and on Cortes web page

- Por Dios y por España; contemporary Carlist propaganda on YouTube