Alfred E. Clarke Mansion

| Alfred E. Clarke Mansion | |

|---|---|

|

The Caselli Mansion or Alfred E. Clarke Mansion in 2009 | |

| Type | Mansion |

| Location | 250 Douglass Street, San Francisco, USA |

| Coordinates | 37°45′35″N 122°26′22″W / 37.75961°N 122.43953°WCoordinates: 37°45′35″N 122°26′22″W / 37.75961°N 122.43953°W |

| Area | Castro District |

| Built | 1891 |

| Original use | Single-Family Residence (Hospital in early 1900s) |

| Architect | Alfred E. Clarke |

| Architectural style(s) | Baroque Queen-Anne[1] |

| Official name: Alfred E. (Nobby) Clarke Mansion[2] | |

| Designated | December 7, 1975 |

| Reference no. | 80[2] |

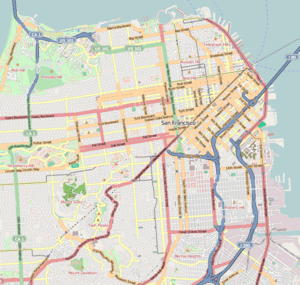

Location of Alfred E. Clarke Mansion in San Francisco | |

The Alfred E. Clarke Mansion, also known as Caselli Mansion, Nobby Clarke's Castle and Nobby Clarke's Folly, is a mansion in San Francisco, California, located at 250 Douglass Street in the Castro neighborhood.[3] The Clarke Mansion survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fires which had destroyed many of the Victorian mansions from the same era.[4] On December 7, 1975, it was designated a San Francisco City landmark.[5] The mansion was used briefly as a hospital. Today, it is used as a rental property, with 15 apartments.

Alfred E. Clarke

![]() This article incorporates text by Mae Silver available under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Mae Silver available under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

An Irish policeman with a very colorful reputation owned the mansion, now an historic landmark, called "Nobby" Clarke's Folly at the corner of Douglass and Caselli Streets in Eureka Valley. Contentious and litigious with flashes of brilliance and community conscience, Clarke was the San Francisco Police Department's version of 'Emperor Norton', the eccentric dictator who ruled downtown streets benevolently in the 1860s and 70s. "Nobby" was both the pride and bane of the Police Force.

Answering the call for gold, Alfred Clarke arrived from Ireland in 1850 aboard the ship "Commonwealth." After an unrewarding attempt in the gold hills of Nevada County, Clarke returned to the city docks and landed a job as stevedore. Restless to do better, he connected himself with the Clerk of the Board of Supervisors and by 1856 was a patrolman on the San Francisco Police Force. On his waterfront beat, he had an altercation with a seaman who bit his hand so badly he never recovered full use of it. Likely, his nickname " Nobby" came from that injury. Clarke moved up the ladder until he was clerk to the Chief of Police. He made an expanded use of that position by running a side business lending money to patrolmen. Soon he was making more money than the Chief and that revelation likely figured in his removal from the Force for the next three years. "Nobby" used that time to his advantage. He studied law and passed the bar. When he returned to the Police Department in 1870, he was chief legal advisor to the department and its Chief.

It was "Nobby" Clarke, the attorney, who introduced "Emperor Norton"-style splashes of excitement, amusement and vexation to the courts of San Francisco. Apparently courtrooms held such an attraction to Clarke, he could hardly stay away from appearing there daily. He filed many, some say, too many cases mostly against the Police Commission or about the Department itself. While his legal demeanor was over zealous, at times he seemed genuinely concerned about his former fellow officers. In 1896 he aimed a suit directly at the Police Commissioners who had discharged 50 patrolmen in 1894. He asked for compensation of $40,000 for each while characterizing the Commissioners as persons with evil eyes, depraved minds and abandoned hearts. Clarke wasn't entirely "off the wall" on this case, in view of the deep depression and rampant unemployment in 1894.

"Nobby" was clearly contentious and maybe a bit proud. After he built, or over built, his mansion in the Gilded Age, he and his upslope neighbor, Behrend Joost, began a feud that lasted their lifetime. While the frequently given reason for the daily warfare was the Mountain Spring Water Company service Joost owned and provided to Clarke and others in Eureka Valley, it is probable these two "rags to riches" businessmen were destined to compete about anything and everything. By then it was their nature to achieve by outdoing everyone else. Their stormy relationship didn't stop with sharp words; neighbors still recount stories of their fist fights on 18th Street.

There was another side to Clarke's character. A soft side that showed sensitive concern for others. He and his first wife were founding members of the Calvary Presbyterian Church with Clarke serving as its Deacon. "Nobby" organized the Widows and Orphans Aid Association of the Police Department and was its president several times. He was involved with other charitable organizations, and "Nobby" was always ready to go to court defending those who were overlooked or ill-used by the system.

Eventually, Clarke himself was chewed up by the system. He became involved with a J.F. Turner, who forced him into bankruptcy. "Nobby" lost his beautiful place in Eureka Valley and moved to 1208 Masonic Avenue where he died of heart problems in 1902. He was 69. Even in his obituaries, the two different sides of Clarke's character emerged. The Examiner portrayed "Nobby" with a gnarled, contentious personality and an uncouth physique in his later years. The Chronicle painted Clarke as short, with a tufted beard and broad shoulders. He was a mild-mannered man who died friendless. The truth is probably some of both.[6]

Caselli Mansion

Clarke purchased seventeen acres of land on a steep slope in the city’s Eureka Valley section. He spent $100,000 (over two million dollars today) to build his impressive mansion—a huge expenditure for any home of that period—completing it in 1892. The style is primarily Queen Anne but with other eclectic features such as turrets, gables and quirky protuberances that make the house more flamboyantly noticeable from all sides. Even the shingled roof alternates scalloped and plain shapes in an interesting pattern.

There is a gracious portico at the top of the exterior entry steps; the spacious foyer within and the grand staircase were meant to induce wonder and are a particularly fine statement of what the eccentric owner wanted to achieve. The interior details include fine paneled woodwork, elegant fireplaces and mantels, as well as high quality stained glass windows throughout.[3]

Although predominantly Queen Anne and Baroque, its style is eclectic (meaning a bit of everything). No two rooms are alike. Some are authentic San Francisco Victorian. Others are designed in the grand Continental manner with rococo and other elaborate ornamentation. The former music room has a Far Eastern flavor. On the fourth floor are Parisian-style garret apartments which were once the servants' quarters. Every room in the house either overlooks the dramatic San Francisco skyline or the garden abounding with flowers and birds.[7]

Sadly, Mr. Clarke could not convince his wife to leave her fashionable residence on Nob Hill, so she and their son never even lived in the house that he had clearly created as a labor of love and imagination for his family.

By 1904, the building had been converted into California General Hospital. An advertisement for the new hospital noted that elegant rooms were a dollar a day, it was the only building in the block, and was sheltered from the cold west wind. Many old-timers in the neighborhood were born in the mansion-turned-hospital.

About 1909 the mansion was tastefully converted into 15 apartments and most of the elegant decor was preserved. It is one of the most sought after buildings in The City in which to reside, with prospective residents often remaining on a waiting list for several years. With 45 rooms on five floors, the mansion is one of the largest formerly private homes still standing in the State. It has 22 stained glass windows. (There are spaces for twice that number, but apparently funds ran short.), 10 fireplaces, 16 baths and 52 closets. The house stands on three city lots with the garden covering the fourth. Small statues and other artifacts have been unearthed in the neighboring grounds which once constituted the grand estate.

In the 20's Victorian architecture fell into disfavor. A 1928 publication comments, "Clarke built this house in the awful architecture of the nineties...It still stands in all its horrific architectural pretensions." Today, of course, Victorians are revered and treasured. Columnist Margo Patterson Doss refers to the mansion's "architectural splendors." The San Francisco Progress calls it "a stunning example of artistic workmanship." The Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board describes it as "imposing and impressive...and when viewed from the Northeast in particular it becomes an olio of architectural details and forms..." In 1975 it was selected by the prestigious organization, San Francisco Beautiful, to receive one of seven beautification awards and shortly after was officially designated an historical landmark by the Landmarks Commission.[7]

References

- ↑ "Historic Sites and Points of Interest in San Francisco". NoeHill. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- 1 2 "SAN FRANCISCO PRESERVATION BULLETIN NO. 9" (PDF). San Francisco Planning Dept. City and County of San Francisco. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- 1 2 "The Victorian Alliance of San Francisco — House Histories". Victorianalliance.org. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- ↑ "San Francisco Adventure / Caselli Mansion". Sfxplorer.com. 2012-01-03. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- ↑ List of San Francisco Designated Landmarks

- ↑ "Alfred "Nobby" Clarke: The Police Department's 'Emperor Norton'". FoundSF. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- 1 2 "The Story of The Mansion". Fuzzygruf.com. 2002-06-30. Archived from the original on 2016-03-13. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

.jpg)