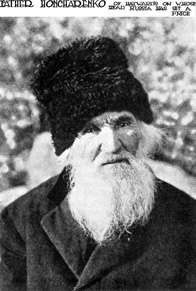

Agapius Honcharenko

Reverend Agapius Honcharenko (Ukrainian: Агапій Онуфрійович, Russian: Агапий Гончаренко; August 31, 1832 – May 5, 1916, real name Andrii Humnytsky (Андрій Гумницький),[1] aka Ahapii or Ahapius) was a Russian and Ukrainian public figure and exiled Greek Orthodox priest. He was a prominent scholar, humanitarian, and early champion for human rights.

Born to a prominent Cossack family (he was a descendant of Ivan Bohun) in Kryva, Tarascha county, in Kyiv Oblast, Honcharenko was the first Ukrainian political émigré to arrive in the United States.[1] He graduated from the Kyiv Theological Seminary and entered the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra. He was sent to Athens in 1857 to serve as deacon at the embassy's church, where he began to contribute anonymous articles to Alexander Herzen's London-based Kolokol that clamored for the emancipation of Russian serfs and denounced his own church for supporting such an unequal system. These articles caused much unrest in Russia, and after months of trying to determine the identity of the mystery writer, Russian authorities discovered and arrested him in 1860. He was able to escape from the Russian prison in Constantinople by disguising himself as a Turk and walking out the front door.[2]

After his escape, he traveled to London to rejoin the Kolokol staff until the newspaper discontinued publication upon the freeing of the serfs, then returned to Athens again. Afterwards, he traveled extensively to Syria, Jerusalem, Egypt and Turkey. While in Alexandria, he served as confessor to Leo Tolstoy.[2] Returning to London, he met Italian patriot Giuseppe Mazzini, who advised him to immigrate to the United States, which he did in 1865. After his arrival, he traveled around the country, first to Philadelphia where he met the woman who would become his wife. In New York City, he established the first Orthodox liturgy in the U.S. outside of Alaska.[3] He also helped establish a Greek Orthodox church in New Orleans and did work in Alaska before finally settling in San Francisco. Before immigrating, he had changed his name to protect his family from persecution for his anti-Russian writings.[1] Through his travels, he became friends with many notable Americans, among them Eugene Schuyler, Horace Greeley, Charles R. Dana, Hamilton Fish, Henry Wager Halleck, William H. Seward and Henry George.[2]

A plain-spoken man, Honcharenko was known to openly denounce his own church for corruption, immorality, and other failings, so much so that he was declared a schismatic. While living in San Francisco, he published The Alaska Herald, aimed at Russian residents of Alaska, from 1868 to 1872, which included both Russian and Ukrainian language supplements. The Russian supplement titled Svoboda (Свобода : Freedom) was the first Russian language newspaper in the U.S.[2]

After founding a farm, "Ukraina Ranch", located in Hayward, California, in 1873, he continued to publish political literature, which was smuggled into Czarist Russia. These actions made him a thorn in the side of pro-Tsarist Russians, who called his writings "the drivelling [sic] of a half crazy old man."[4]

He and his wife Albina are buried on the farm, which is now registered as California Historical Landmark #1025, located in Garin Regional Park near California State University, Hayward.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 Lewytzkyj, Maria (June 20, 1999). "California dedicates new historic landmark: Ukraina". The Ukrainian Weekly. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tolstoi's Confessor Long an Exile in California". San Francisco Call. April 9, 1911. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ↑ Namee, Michael. "The First Orthodox Liturgy in New York City". OrthodoxHistory.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ↑ "Our Foes". Orthodox American Messenger. December 27, 1896. p. 140.

- ↑ "Ukrania, Site of Agapius Honcharenko Farmstead". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-03-30.