AIM-54 Phoenix

| AIM-54 Phoenix | |

|---|---|

Six AIM-54 Phoenix missiles seen mounted on the belly and wing gloves of a U.S. Navy F-14B in January 1989 | |

| Type | Long-range air-to-air missile |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1974–2004 |

| Used by |

United States Navy (former) Iranian Air Force |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer |

Hughes Aircraft Company Raytheon Corporation |

| Unit cost | US$477,131 |

| Produced | 1966 |

| Specifications | |

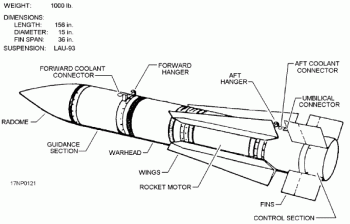

| Weight | 1,000–1,040 lb (450–470 kg) |

| Length | 13 ft (4.0 m) |

| Diameter | 15 in (380 mm) |

| Warhead | 135 lb (61 kg), high explosive |

Detonation mechanism | Proximity fuze |

|

| |

| Engine | Solid propellant rocket motor |

| Wingspan | 3 ft (910 mm) |

Operational range | 100 nmi (190 km) |

| Flight ceiling | 100,000 ft (30 km) |

| Flight altitude | 80,000 ft (24 km) |

| Speed | Mach 5[1] |

Guidance system | Semi-active radar homing and terminal phase active radar homing |

Launch platform | Grumman F-14 Tomcat |

The AIM-54 Phoenix is a radar-guided, long-range air-to-air missile (AAM), carried in clusters of up to six missiles on the Grumman F-14 Tomcat, its only operational launch platform. The Phoenix was the United States' only long-range air-to-air missile. The combination of Phoenix missile and the AN/AWG-9 guidance radar was the first aerial weapons system that could simultaneously engage multiple targets. Both the missile and the aircraft were used by the United States Navy and are now retired, the AIM-54 Phoenix in 2004 and the F-14 in 2006. They were replaced by the shorter-range AIM-120 AMRAAM, employed on the F/A-18 Hornet and F/A-18E/F Super Hornet. Following the retirement of the F-14 by the U.S. Navy, the weapon's only current operator is the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force. Brevity code "Fox Three" was used when firing the AIM-54.

Development

Background

Since 1951, the Navy faced the initial threat from the Tupolev Tu-4K 'Bull' carrying[2] anti-ship missiles. Eventually, during the height of the Cold War, the threat would have expanded into regimental-size raids of Tu-16 Badger and Tu-22M Backfire bombers equipped with low-flying, long-range, high-speed, nuclear-armed cruise missiles and considerable electronic countermeasures (ECM) of various types.

The Navy would require a long-range, long-endurance interceptor aircraft to defend carrier battle groups against this threat. The proposed F6D Missileer was intended to fulfill this mission and oppose the attack far from the fleet it was defending. The weapon needed for interceptor aircraft, the Bendix AAM-N-10 Eagle, was to be an air-to-air missile of unprecedented range when compared to contemporary AIM-7 Sparrow missiles. It would work together with Westinghouse AN/APQ-81 radar. The Missileer project was cancelled in December 1960.

AIM-54

In the early 1960s, the U.S. Navy made the next interceptor attempt with the F-111B, and they needed a new missile design. At the same time, the USAF canceled the projects for their land-based high-speed interceptor aircraft, the North American XF-108 Rapier and the Lockheed YF-12, and left the capable AIM-47 Falcon missile at a quite advanced stage of development, but with no effective launch platform.

The AIM-54 Phoenix, developed for the F-111B fleet air defense fighter, had an airframe with four cruciform fins that was a scaled-up version of the AIM-47. One characteristic of the Missileer ancestry was that the radar sent it mid-course corrections, which allowed the fire control system to "loft" the missile up over the target into thinner air where it had better range.

The F-111B was canceled in 1968. Its weapons system, the AIM-54 working with the AWG-9 radar, migrated to the new U.S. Navy fighter project, the VFX, which would later become the F-14 Tomcat.

In 1977, development of a significantly improved Phoenix version, the AIM-54C, was developed to better counter projected threats from tactical anti-naval aircraft and cruise missiles, and its final upgrade included a re-programmable memory capability to keep pace with emerging ECM.[3]

Usage in comparison to other weapon systems

The AIM-54/AWG-9 combination had multiple track capability (up to 24 targets) and launch (up to 6 Phoenixes can be launched nearly simultaneously); the large 1,000 lb (500 kg) missile is equipped with a conventional warhead.

On the F-14, four missiles can be carried under the fuselage tunnel attached to special aerodynamic pallets, plus two under glove stations. A full load of 6 Phoenix missiles and the unique launch rails weighs in at over 8,000 lb (3,600 kg), about twice the weight of Sparrows, so it was more common to carry a mixed load of 4 Phoenix, 2 Sparrow, and 2 Sidewinder missiles.

Most other US aircraft relied on the smaller, semi-active medium-range AIM-7 Sparrow. Semi-active guidance meant the aircraft no longer had a search capability while supporting the launched Sparrow, reducing situational awareness.

The Tomcat's radar could track up to 24 targets in track-while-scan mode, with the AWG-9 selecting up to 6 potential targets for the missiles. The pilot or radar intercept officer (RIO) could then launch the Phoenix missiles once parameters were met. The large tactical information display (TID) in the RIO's cockpit gave information to the aircrew (the pilot had the ability to monitor the RIO's display) and the radar could continually search and track multiple targets after Phoenix missiles were launched, thereby maintaining situational awareness of the battlespace.

The Link-4 datalink allowed US Navy Tomcats to share information with the E-2C Hawkeye AEW aircraft. During Desert Shield in 1990, the Link-4A was introduced; this allowed the Tomcats to have a fighter-to-fighter datalink capability, further enhancing overall situational awareness. The F-14D entered service with the JTIDS that brought the even better Link-16 datalink "picture" to the cockpit.

Active guidance

The Phoenix has several guidance modes and achieves its longest range by using mid-course updates from the F-14A/B AWG-9 radar (APG-71 radar in the F-14D) as it climbs to cruise between 80,000 ft (24,000 m) and 100,000 ft (30,000 m) at close to Mach 5. Phoenix uses this high altitude to gain gravitational potential energy, which is later converted into kinetic energy as the missile dives at high velocity towards its target. At around 11 miles (18 km) from the target, the missile activates its own radar to provide terminal guidance.[4] Minimum engagement range for the Phoenix is around 2 nmi (3.7 km) and active homing would initiate upon launch.[4]

Service history

U.S. combat experience

- On January 5, 1999, a pair of US F-14s fired two Phoenixes at Iraqi MiG-25s southeast of Baghdad. Both AIM-54s' rocket motors failed and neither missile hit its target.[5][6]

- On September 9, 1999 another US F-14 launched an AIM-54 at an Iraqi MiG-23 that was heading south into the no-fly zone from Al Taqaddum air base west of Baghdad. The missile missed, eventually going into the ground after the Iraqi fighter reversed course and fled north.[7]

The AIM-54 Phoenix was retired from USN service on September 30, 2004. F-14 Tomcats were retired on September 22, 2006. They were replaced by shorter-range AIM-120 AMRAAMs, employed on the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet.

Despite the much-vaunted capabilities, the Phoenix was rarely used in combat, with only two confirmed launches and no confirmed targets destroyed in US Navy service, though a large number of kills were claimed by Iranian F-14s during the Iran–Iraq War. The USAF F-15 Eagle had responsibility for overland combat air patrol duties in Operation Desert Storm in 1991, primarily because of the onboard F-15 IFF capabilities. The Tomcat did not have the requisite IFF capability mandated by the JFACC to satisfy the rules of engagement to utilize the Phoenix capability at beyond visual range. The AIM-54 was not adopted by any foreign nation besides Iran, or any other US armed service, and was not used on any aircraft other than the F-14.

Iranian combat experience

There is very little information available regarding Iran's use of its 79 F-14A Tomcats (delivered prior to 1979) in most western outlets; the exception being a book released by Osprey Publishing titled Iranian F-14 Tomcats in Combat by Tom Cooper and Farzad Bishop.[8] Most of the research contained in the book was based on pilot interviews. Reports vary on the use of the 285 missiles supplied to Iran,[9] during the Iran–Iraq War, 1980–88.

According to Cooper, the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force was able to keep its F-14 fighters and AIM-54 missiles in regular use during the entire Iran–Iraq War, though periodic lack of spares grounded large parts of the fleet at times. At worst, during late 1987, the stock of AIM-54 missiles was at its lowest, with fewer than 50 operational missiles available. The missiles needed fresh thermal batteries that could only be purchased from the US. Iran found a clandestine buyer that supplied it with batteries—though those did cost up to US$10,000 each. Iran did receive spares and parts for both the F-14s and AIM-54s from various sources during the Iran–Iraq War, and has received more spares after the conflict. Iran started a heavy industrial program to build spares for the planes and missiles, and although there are claims that it no longer relies on outside sources to keep its F-14s and AIM-54s operational, there is evidence that Iran continues to procure parts clandestinely.[10]

Both the F-14 Tomcat and AIM-54 Phoenix missile continue in the service of the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force, although the operational abilities of these aircraft and the missiles are questionable, since the US refused to supply spare parts and maintenance after the 1979 revolution, except for a brief period during the Iran-Contra Affair.

Iran claimed to be working on building an equivalent missile[11] and in 2013 unveiled the Fakour-90, an upgraded and reverse-engineered version of the Phoenix.[12]

Variants

- AIM-54A

- Original model that became operational with the U.S. Navy in about 1974, and it was also exported to Iran before the Iran hostage crisis beginning in 1979.

- AIM-54B

- Also known as the 'Dry' missile. A version with simplified construction and no coolant conditioning. Did not enter series production. Developmental work started in January 1972. 7 X-AIM-54B missiles were created for testing, 6 of them by modifying pilot production IVE/PIP rounds. After two successful test firings, the 'Dry' missile effort was cancelled for being "not cost effective".[13]

- AIM-54C

- The only improved model that was ever produced. It used digital electronics in the place of the analog electronics of the AIM-54A. This model had better abilities to shoot down low and high-altitude antiship missiles. This model took over from the AIM-54A beginning in 1986.

- AIM-54 ECCM/sealed round

- More capabilities in electronic counter-countermeasures. It did not require coolant conditioning during flights on board F-14s and not fired (the usual situation). Deployed beginning in 1988. Because the AIM-54 ECCM/Sealed received no coolant, F-14s carrying this version of the missile could not exceed a specified airspeed.

There were also test, evaluation, ground training, and captive air training versions of the missile; designated ATM-54, AEM-54, DATM-54A, and CATM-54. The flight versions had A and C versions. The DATM-54 was not made in a C version as there was no change in the ground handling characteristics.

- Sea Phoenix

- A 1970s proposal for a ship launched version of the Phoenix as an alternative/replacement for the Sea Sparrow point defense system. It would also have provided a medium-range SAM capability for smaller and/or non-Aegis equipped vessels (such as the CVV). The Sea Phoenix system would have included a modified shipborne version of the AN/AWG-9 radar. Hughes Aircraft touted the fact that 27 out of 29 major elements of the standard (airborne) AN/AWG-9 could be used in the shipborne version with little modification. Each system would have consisted of one AWG-9 radar, with associated controls and displays, and a fixed 12-cell launcher for the Phoenix missiles. In the case of an aircraft carrier, for example, at least three systems would have been fitted in order to give overlapping coverage throughout the full 360°.[14] Both land and ship based tests of modified Phoenix (AIM-54A) missiles and a containerised AWG-9 (originally the 14th example off the AN/AWG-9 production line) were successfully carried out from 1974 onwards.[15]

- AIM-54B

- A land based version for the USMC was also proposed. It has been suggested that the AIM-54B would have been used in operational Sea Phoenix systems, although that version had been cancelled by the second half of the 1970s. Ultimately, a mix of budgetary and political issues meant that, despite being technically and operationally attractive, further development of the Sea Phoenix did not proceed.

- Fakour 90

- In February 2013 Iran reportedly tested an indigenous long-range air-to-air missile.[16] In September 2013 it displayed Fakour-90 on a military parade. It looked almost identical to AIM-54 Phoenix.[17]

Operators

Current operators

Former operators

United States - United States Navy: Retired in 2004

United States - United States Navy: Retired in 2004

Characteristics

The following is a list of AIM-54 Phoenix specifications:[18]

- Primary function: long-range, air-launched, air-intercept missile

- Contractor: Hughes Aircraft Company and Raytheon Corporation

- Unit cost: about $477,000, but this varied greatly

- Power plant: solid propellant rocket motor built by Hercules Incorporated

- Length: 13 ft (4.0 m)

- Weight: 1,000–1,040 pounds (450–470 kg)

- Diameter: 15 in (380 mm)

- Wing span: 3 ft (910 mm)

- Range: over 100 nautical miles (120 mi; 190 km) (actual range is classified)

- Speed: 3,000+ mph (4,680+ km/h)

- Guidance system: semi-active and active radar homing

- Warheads: proximity fuze, high explosive

- Warhead weight: 135 pounds (61 kg)

- Users: US (U.S. Navy), Iran (IRIAF)

- Date deployed: 1974

- Date retired (U.S.): September 30, 2004

See also

- AIM-152 AAAM (Proposed successor.)

- AIM-47 Falcon

- Vympel R-33 (AA-9 Amos), the Russian air-to-air missile most similar to the AIM-54 Phoenix, and R-37 (missile)

- FMRAAM

- Meteor (missile)

- List of missiles

- Missile designation

- Combat history of the F-14

- Related lists

References

- ↑ the great book of modern warplanes. New York, New York: Salamander Books Ltd. 1987.

- ↑ Zaloga, S.J.; Laurier, J. (2005). V-1 Flying Bomb, 1942-52: Hitler's Infamous "Doodlebug". Osprey Publishing, Limited. ISBN 9781841767918. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ↑ "Raytheon AIM-54 Phoenix". designation-systems.net. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- 1 2 "AIM-54". (2004) Directory of US Military Rockets and Missiles. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ↑ "Defense.gov Transcript: DoD News Briefing January 5, 1999".

- ↑ Parsons, Dave, George Hall and Bob Lawson. (2006). Grumman F-14 Tomcat: Bye-Bye Baby...!: Images & Reminiscences From 35 Years of Active Service. Zenith Press, p. 73. ISBN 0-7603-3981-3.

- ↑ Tony Holmes, "US Navy F-14 Tomcat Units of Operation Iraqi Freedom", Osprey Publishing (2005). Chapter One – OSW, pp. 16–7.

- ↑ "Book: Iranian F-14 Tomcat Units in Combat". Acig. Archived from the original on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ↑ "Iranian Air Force F-14". Aerospace Web. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ↑ Theimer, Sharon. "Iran Gets Army Gear in Pentagon Sale". Forbes. Archived from the original on 19 January 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ↑ Iran eyes missile stronger than Phoenix, IR: Press TV.

- ↑ Cenciotti, David. "The Aviationist » Iranian F-14 Tomcat's "new" indigenous air-to-air missile is actually an (improved?) AIM-54 Phoenix replica". Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Weapon Systems, Jane's, 1977.

- ↑ Tarpgaard, PT (1976), "The Sea Phoenix—A Warship Design Study", ASNE, 88 (2): 31–44.

- ↑ Iran test-fires latest air-to-air missile, IR: Press TV, Feb 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Farouk missile", The Avionist, Sep 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Fact File: AIM-54 Phoenix Missile". U.S. Navy. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to AIM-54 Phoenix. |