2012 Olympic Marathon Course

The 2012 Olympic Marathon Course is that of both the men's and women's marathon races at the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games in London.

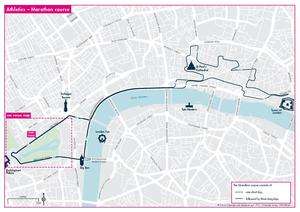

The 42.195-kilometre (26.219-mile) route consists of one short circuit of 3.571 kilometres (2.219 miles) followed by three circuits of 12.875 kilometres (8.0 miles). The course, which was designed to pass many of London's well-known landmarks, starts and finishes on The Mall, within sight of Buckingham Palace, and extends as far as the Tower of London in the east and the Victoria Memorial in the west.

The route of the marathon had been changed, for various logistical reasons, from that originally envisaged in London's original 2005 bid for the Games and now breaks with the normal Olympic tradition that the race finishes inside the main Olympic Stadium.

The 2012 Summer Olympics is the third to be held in London. The stated distance of the marathon at the London 1908 Summer Olympics – 26 miles and 385 yards, later converted to metric units as 42.195 kilometres – formed the basis of the standard distance adopted by International Association of Athletics Federations in 1921.

The course

A later map (May 2012 version)[1] shows several small changes, e.g. Bank junction being approached from Princes Street, not Threadneedle Street, as in this map.

The route, as confirmed in October 2010, starts on The Mall about 350 metres from the Victoria Memorial[nb 1] and has four laps, finishing at the start point. It follows the Victoria Embankment towards the City of London where it takes a winding route and continues eastwards to Tower Hill. At this point there is a U-turn and the route heads westwards, again using the Embankment as far as the Palace of Westminster and thence back to The Mall. The last three laps are identical and are exactly 8 miles (12.875 km) each. The first lap, which only incorporates the south-western section of the route, is 2 miles and 385 yards (3.571 km) long.[2][3]

A summary of the course and associated distance points is given below:

| Lap | Distance | Mile points | Kilometre points [nb 2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km | mile | |||

| 1 | 3.571 | 2.2 | 1,2 | None |

| 2 | 16.445 | 10.2 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 | 5, 10, 15 |

| 3 | 29.320 | 18.2 | 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 | 20, half-way, 25 |

| 4 | 42.195 | 26.2 | 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 | 30, 35, 40 |

Route description

Runner's World described the course as "picturesque" as well as "labyrinthine", noting that included among the 111 turns or bends are four U-turns.[4]

The marathon route starts part way along The Mall and, heading away from Buckingham Palace proceeds through Admiralty Arch and past Nelson's Column in Trafalgar Square. A slight turn to the right onto Northumberland Avenue which drops down to near river-level over a distance of 350 metres (a little under a quarter of a mile).[5] On the first lap the runners turn right and continue along the Victoria Embankment, on subsequent laps they turn left and pass under the Hungerford Bridge and follow the River Thames on its downstream path. The Embankment is the longest "straight"[nb 3] stretch in the race, about 1,500 m (nearly a mile) on the outbound leg and 2,100 m on the return leg. It leads the runners past Cleopatra's Needle and the heraldic lions that symbolically defend the limits of the City of London.

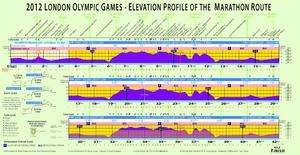

After Blackfriars station (at the end of the Embankment), the course climbs Puddle Dock, a short but steep 16 metre hill[6] from Upper Thames Street to Queen Victoria Street[7] which is paved with cobblestones, before reaching the race's highest point of 18 metres[6] on Ludgate Hill close to the south portal of St Paul's Cathedral.

The route passes around the west end of the cathedral, across Paternoster Square, behind St Bartholomew's Hospital and eventually along a winding route including St. Martin's Le Grand, onto Cheapside. On the third lap, runners cross the half way mark within sight of St Mary-le-Bow and within earshot of the "Bow Bells". Leaving Cheapside, the route then goes through the heart of the City, past the offices of many of the world's best known (and lesser known) banks into the Guildhall Yard, home of the Corporation of London. From the Guildhall, the route passes the Bank of England at Bank junction and down Cornhill, passing the Royal Exchange. At the end of Cornhill, continuing onto a small portion of Leadenhall Street, a right-turn takes the runners into the covered Leadenhall Market. Competitors then make their way onto Eastcheap, via Fenchurch Street and Gracechurch Street, and on towards the Tower of London.

On Tower Hill, a short distance from the Tower's moat, the course makes a U-turn back to Lower Thames Street at the start of the return leg. Leaving Lower Thames Street, the route reaches The Monument dedicated to the Great Fire of London. After The Monument, the return leg has far fewer bends than the outward leg, as it takes the runners along the relatively straight and flat 1,600 m stretch following Cannon Street and back onto Queen Victoria Street. An S-bend takes the runners back onto the Victoria Embankment, at the far end of which are the Houses of Parliament. About 600 m before the end of the Embankment they rejoin the route taken on the first lap and pass the London Eye on the opposite side of the river. On the first lap, runners turn left onto Westminster Bridge, making a U-turn on the bridge before rejoining the main route. On the other laps, runners turn right at the end of the Embankment, and continue past Big Ben and Parliament Square and towards Buckingham Palace via Birdcage Walk on the periphery of St. James Park. As the runners approach the palace, another right turn brings the Victoria Memorial into view. The memorial, at the south-western end of the kilometre-long Mall, brings them past the start line which, on the last circuit, is also the finish line.

The distances relative to the lap start point of various prominent landmarks passed on the route are shown in the table below:[3]

| Landmarks passed relative to lap start point | ||

|---|---|---|

| km | mile | |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | The Mall near Marlborough Road |

| 0.7 | 0.4 | Trafalgar Square |

| 1.3 | 0.8 | Cleopatra's Needle (outbound leg) |

| 3.5 | 2.2 | St Paul's Cathedral |

| 4.7 | 2.9 | St Mary-le-Bow |

| 5.0 | 3.1 | Guildhall |

| 5.3 | 3.3 | Bank of England |

| 5.8 | 3.6 | Leadenhall Market |

| 6.9 | 4.3 | Tower of London from Tower Hill |

| 7.6 | 4.7 | The Monument |

| 10.3 | 6.4 | Cleopatra's Needle (return leg) |

| 10.9 | 6.8 | Across from the London Eye |

| 11.3 | 7.0 | Palace of Westminster |

| 12.5 | 7.8 | Victoria Memorial |

| 12.875 | 8.000 | The Mall near Marlborough Road |

Changes to original proposal

When London submitted its bid for the Olympic Games in 2004, the bid chairman Sebastian Coe said: "The marathon course has been designed to include as many of the city's landmarks as possible".[8] Although the final route is different from the one proposed in the bid, it still passes many notable landmarks.

Originally the route was planned to start at Tower Bridge, run through Tower Hamlets and finish at the Olympic Stadium.[9] It would have had a 580 m "run-in", three laps of 11.61 km circuiting central London and passing through or close to the Tower of London, the Victoria Embankment, the Palace of Westminster, Parliament Square, Westminster Abbey, Birdcage Walk, Green Park, Buckingham Palace, the Mall, Trafalgar Square, Strand, St Paul's Cathedral, and the City of London. After the final circuit, the route would then have headed east for 7.34 km, along Whitechapel Road and Mile End Road, towards the Olympic Park and a finish in the Olympic Stadium.[10][11]

In September 2010 it was reported that the London Organising Committee were considering alternative routes for the 2012 Olympic Marathon as the original route would not be "television-friendly" in London's East-end.[12][13] After details of the new route had been published, the organisers defended their decision on grounds that the original route would have potentially disrupted other events due to road closures.[14] The changes rerouted the section between Trafalgar Square and St Paul's Cathedral from The Strand to the Victoria Embankment (past Cleopatra's Needle) which would then be bi-directional. It also removed Whitechapel Road and Tower Bridge from the route, while adding the Guildhall Yard and Leadenhall Market. The removal of The Strand from the route allows Waterloo Bridge and Blackfriars Bridge to remain open to traffic.

On 27 May 2012, less than two months before the event, The Sunday Times reported another potential logistical problem facing games organisers. In light of the size of the crowds turning out to watch the torch relay, estimates of crowd sizes for the marathon were revised and now suggest that up to 1.5 million people might turn up to watch the event. As there is only a pavement capacity of about 150,000 along the key streets of the event, contingency plans to avoid dangerous overcrowding are being considered.[15]

Official measurement of the course

The official measurement of the course took place at 2 a.m. on 13 June 2012.[16] It was carried out by David Katz, a member of the IAAF Technical Committee, using a bicycle fitted with a Jones Counter. He was accompanied by two other measurers: Hugh Jones of London, who estimated he had been over the course more than 20 times in the 10 years since London first started assembling its bid, and Mike Sandford.

Compliance with international rules and testing

All international competitions in athletics, including the Olympic games, are governed under the rules of the International Association of Athletics Federations.[17][18] The IAAF rules define the standard length of the marathon as 42.195 km and specifically state that the course must not be less than this distance.[19] The rules further state that in Olympic competition the standard distance may not be exceeded by more than 0.1%.[20] In order for a marathon performance to be ratified as a world record by the IAAF, the course must also meet other criteria that rule-out "artificially fast times" produced on courses aided by downhill slope or tailwind: the distance between start and end points when measured in a straight line should not exceed 50% of the length of the course (21.092 km in the case of the marathon); and the difference in altitude between the start and end points should be no more than 0.1% of the course length (42.19 m).[21] World records for intermediate distances (i.e. 5 km, 10 km, 20 km, and 30 km) must meet similar requirements.[22] The rules also state that "the distance in kilometres on the route shall be displayed to all athletes"[23] and require that water and refreshments be provided at approximately 5 km intervals.[24]

A successful test of the course, its technology and technical aspects, was completed in May 2011 when a test event of the full marathon distance was held. The event included thirty-nine elite athletes.[25]

Performances on the course

The Daily Telegraph reported that runners, who took part in the test event in May 2011, said that a world record would not be set on the course due to its windy layout and the later start times,[25] a view echoed in reports in Competitor and Runner's World magazines.[7][26] Commentators also noted that the cobblestones on the "brief but steep" hill in the vicinity of St Pauls would present further challenges to the runners.[26]

In the women's marathon that took place on Sunday 5 August 2012, Tiki Gelana of Ethiopia set a new women's marathon Olympic record of 2:23:07,[27] clipping 7 seconds off the previous record. The new Olympic record was 7min 42sec slower than Paula Radcliffe's world record set in 2003 during the London Marathon.

The winning time of 2:08:01 by Stephen Kiprotich of Uganda[28] in the men's marathon, on 12 August 2012, was 1:29 outside the Olympic marathon record and 4:23 outside the world marathon record.

The winners of the Paralympic marathon events were:[29]

- T12 Men's Marathon - Alberto Suarez Laso - 2:24:50, a new world record.

- T46 Men's Marathon - Tito Sena - 2:30:40, 3:37 slower than the world record of 2:27:04 set in 2008.

- T54 Men's Marathon - David Weir - 1:30:20, 10:06 slower than the world record of 1:20:14 set in 1999.

- T54 Women's Marathon - Shirley Reilly - 1:46:33, 8:01 slower than the world record of 1:38:32 set in 2001.

Comparisons with the London Marathon course

The 2012 Olympic route differed significantly from that of the long-established annual London Marathon. Although the Olympic route shared a finish in The Mall and a section along the Victoria Embankment with the regular London Marathon course,[30] the Olympic event also started in The Mall whilst the London Marathon starts in Greenwich, and the event followed an otherwise different course. The logistical problems behind the design of the London Marathon course (35,000 runners of mixed ability) are very different from those behind the design of the London Olympic Marathon course (100 top-class runners) hence the difference in the routes.[31]

London 2012 Paralympic Marathon comparison

The course for the Paralympic Marathon[32] also had four laps which were nearly identical to the 2012 Olympic Marathon course, but avoided certain cobbled areas – notably Paternoster Square, the Guildhall Yard, Leadenhall Market and the Monument.[33] The start and finish lines on The Mall are separated.

Previous London Olympic routes

London has hosted the Olympic games on two previous occasions – in 1908 and in 1948. The marathon route was different on both occasions and the 2012 route follows yet another route.

1908 route

The 1908 games were originally to have been held in Rome, but in April 1906 Mount Vesuvius erupted causing damage to nearby Naples. Italy did not have the resources to stage the games and to rebuild Naples, so London was asked to stage the games.[34] At this time there was no standard length for a marathon, and the 1908 marathon course was originally to have been 25 miles, passing through Uxbridge, Ruislip, Harrow-on-the-Hill before ending at the White City Stadium.[35] It was extended to 26 miles and 385 yards (42.195 km) to avoid troublesome cobbles and tram lines, because of access restrictions at Windsor Castle and to improve visibility to the spectators, including Queen Alexandra, for the finishing stretch inside the stadium.[36] This distance subsequently became the official length of the marathon.[37]

1948 route

In 1948, London hosted the first Olympic Games to be held after World War II – the "austerity games". The marathon started and ended at the Wembley Stadium. It was only three years since the end of the war and London still had considerable bomb damage. Unlike the 2012 games, where the route was chosen to show off central London, the 1948 marathon was run along a route that took the runners from Wembley, through Mill Hill, the towns of Borehamwood, Elstree and Radlett and back to Wembley, thereby avoiding the bomb damage in central London.[38][39]

See also

- Athletics at the 2012 Summer Olympics – Men's marathon (12 August 2012)

- Athletics at the 2012 Summer Olympics – Women's marathon (5 August 2012)

- 2012 Summer Paralympics (9 September 2012)

Notes

- ↑ This reference shows the 26 mile mark as being in front of the Victoria Memorial leaving 385 yards (350 metres) to the end point (which is also the start point).

- ↑ The time taken to cover intermediate distances as measured at the midway point and at the 5 km splits may be eligible for recognition by the IAAF as world records.

- ↑ In reality this section follows a meander of the Thames of radius 500 m.

References

- ↑ "Marathon route map (May 2012 version)" (PDF). London 2012 Committee. May 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Marathons to start and finish in The Mall". London 2012 Organising Committee. 4 October 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- 1 2 "London Olympic Games 2012 Marathon Route" (PDF). London Olympic Committee. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

Offsets from markers on map calculated by interpolation. - ↑ Weldon, Nick (September 2012). Willey, David, ed. "Twist & Shout". Runners World. Emmaus, Pennsylvania: Rodale, Inc.: 75–77.

- ↑ Computed from Google Earth on 31 May 2012; cross-checked on 176 West London (Map). 1:50 000. OS Landranger. Ordnance Survey.

- 1 2 Hartnett, Sean. "2012 London Olympic Games - Elevation profile of the Marathon Route" (PDF).

- 1 2 Monti, David (24 April 2012). "Olympic Marathon Course Goes Round & Round". San Diego, California: 2012 Competitor Group, Inc. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ "2012 Marathon Route Announced". Daily Mail. 17 November 2004. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ "London Landmarks To Star in Olympic Marathon Spectacular". The London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Limited. 17 November 2004. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ↑ "London 2012 Marathon Route". The London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Limited. Archived from the original on 23 September 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ↑ "Marathon Stars Endorse 2012 Route". The London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Limited. 15 April 2005. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ↑ John Hyde (22 September 2010). "Fight Begins To Bring 2012 Olympic Marathon to East London". The Docklands 24. London. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ↑ Mathew Beard and Ross Lyndall (27 September 2010). "2012 chiefs accused of betrayal after ditching East End Marathon route". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 29 September 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ↑ Gibson, Owen (19 November 2010). "Protests fail to sway Coe over change of London Olympic marathon route". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ "Marathon crush fear". The Sunday Times. London. 27 May 2012. p. 11.

- ↑ Robinson, Joshua (20 June 2012). "A Marathon of Measurements". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ International Association of Athletics Federations (1 November 2009). "IAAF Competition Rules 2012–2013" (pdf). Monaco: International Association of Athletics Federations. pp. 19, 113. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ "Olympic Charter in force as from 8 July 2011" (PDF). Lausanne, Switzerland: International Olympic Committee. Rule 46 - Technical responsibilities of the IFs [international federations] at the Olympic Games. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ↑ International Association of Athletics Federations 2009, p. 224.

- ↑ International Association of Athletics Federations 2009, pp. 233–234.

- ↑ International Association of Athletics Federations 2009, p. 244.

- ↑ International Association of Athletics Federations 2009, p. 245.

- ↑ International Association of Athletics Federations 2009, p. 234.

- ↑ International Association of Athletics Federations 2009, p. 235.

- 1 2 Magnay, Jacquelin (30 May 2011). "London 2012 Olympics: Inspiring Marathon Course Given Thumbs Up by Athletes After Test Event". The Daily Telegraph.

- 1 2 Gambaccini, Peter (24 April 2012). "Olympic Marathon Course Has Lots of Turns". Runner's World. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ "Olympics marathon: Ethiopia's Tiki Gelana wins gold in record time". BBC Sport Olympics. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ "Men's Marathon Results". BBC Sports. 12 August 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ "Athletics - Schedule & Results". Official London 2012 website. 9 September 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ↑ "London gets set for Marathon". The London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Limited. 20 April 2007. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ↑ Beard, Mathew (24 May 2010). "A Glimpse of the London Olympic Marathon Course?". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ "Paralympic Marathon route map (May 2012 version)" (PDF). London 2012 Committee. May 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ "Travel in City of London Will Be Affected During the Games: Plan Ahead for Easier Journeys" (PDF). Mayor of London and Transport for London. June 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ↑ Halliday, Stephen (2008). "London's Olympics, 1908". History Today. 58 (4).

- ↑ Burns, Peter (2008). "The Centenary Marathon – Windsor to White City" (PDF). Road Runners Club. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Wilcock, Bob (March 2008). "The 1908 Olympic Marathon". Journal of Olympic History. Volume 16 Issue 1.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/0/olympics/19171204

- ↑ "Athletics at the 1948 London Summer Games: Men's Marathon". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Edwards, Sarah (8 July 2008). "A Trip Down Marathon Lane". Retrieved 28 May 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2012 Olympic Marathon Course. |

- "London Olympic Games 2012 Marathon Route" (PDF). Official site of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Retrieved 12 January 2012.