1961 Ndola United Nations DC-6 crash

|

A DC-6 similar to the accident aircraft | |

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | September 18, 1961 |

| Summary | Controlled flight into terrain |

| Site |

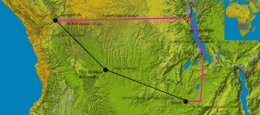

15 km (9.3 mi) W of Ndola Airport (NLA) Zambia 12°58′31″S 28°31′22″E / 12.97528°S 28.52278°ECoordinates: 12°58′31″S 28°31′22″E / 12.97528°S 28.52278°E |

| Passengers | 11 |

| Crew | 5 |

| Fatalities | 16 (15 initially) |

| Injuries (non-fatal) | 0 (1 initially) |

| Survivors | 0 (1 initially) |

| Aircraft type | Douglas DC-6B |

| Operator | Transair Sweden for the United Nations |

| Registration | SE-BDY |

| Flight origin | Elisabethville Airport Congo |

| Stopover | Léopoldville-N'Djili Airport (FIH/FZAA), Congo |

| Destination | Ndola Airport (NLA/FLND), Zambia |

The Ndola United Nations DC-6 crash happened on 18 September 1961. Dag Hammarskjöld, the second Secretary-General of the United Nations and 15 others died. Hammarskjöld's death occurred en route to cease-fire negotiations.

Incident

In September 1961, Hammarskjöld learned about fighting between "non-combatant" UN forces and Katangese troops of Moise Tshombe; on 18 September Hammarskjöld was en route to negotiate a cease-fire when the aircraft he was flying in crashed near Ndola, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). Hammarskjöld and fifteen others perished in the crash.

Aircraft

The aircraft involved in this accident was a Douglas DC-6B, c/n 43559/251, registered in Sweden as SE-BDY, first flown in 1952 and powered by four Pratt & Whitney R-2800 18-cylinder radial piston engines.

UN special report

A special report issued by the United Nations following the crash stated that a bright flash in the sky was seen at approximately 1:00.[1] According to the UN special report, it was this information that resulted in the initiation of search and rescue operations. Initial indications that the crash might not have been an accident led to multiple official inquiries and persistent speculation that the Secretary-General was assassinated.[2]

Official inquiry

Following the death of Hammarskjöld, there were three inquiries into the circumstances that led to the crash:[3] the Rhodesian Board of Investigation, the Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry, and the United Nations Commission of Investigation.

The Rhodesian Board of Investigation looked into the matter between 19 September 1961 and 2 November 1961[3] under the command of British Lt. Colonel M.C.B. Barber. The Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry held hearings from 16–29 January 1962 without United Nations oversight. The subsequent United Nations Commission of Investigation held a series of hearings in 1962 and in part depended upon the testimony from the previous Rhodesian inquiries.[3] Five "eminent persons" were assigned by the new Secretary-General to the UN Commission. The members of the commission unanimously elected Nepalese diplomat Rishikesh Shaha to head an inquiry.[3]

The three official inquiries failed to determine conclusively the cause of the crash that led to the death of Hammarskjöld. The Rhodesian Board of Investigation sent 180 men to search a six-square-kilometer area of the last sector of the aircraft's flight-path, looking for evidence as to the cause of the crash. No evidence of a bomb, surface-to-air missile, or hijacking was found. The official report stated that two of the dead Swedish bodyguards had suffered multiple bullet wounds. Medical examination, performed by the initial Rhodesian Board of Investigation and reported in the UN official report, indicated that the wounds were superficial, and that the bullets showed no signs of rifling. They concluded that the bullets' cartridges had exploded in the fire in proximity to the bodyguards.[3] No other evidence of foul play was found in the wreckage of the aircraft.[4]

Previous accounts of a bright flash in the sky were dismissed as occurring too late in the evening to have caused the crash. The UN report speculated that these flashes may have been caused by secondary explosions after the crash. Sergeant Harold Julien, who initially survived the crash but died days later,[5] indicated that there was a series of explosions that preceded the crash.[3][6] The official inquiry found that the statements of witnesses who talked with Julien before he died in hospital five days after the crash[7] were inconsistent.

The report states that there were numerous delays that violated the established search and rescue procedures. There were three separate delays: the first delayed the initial alarm of a possible plane in trouble; the second delayed the "distress" alarm, which indicates that communications with surrounding airports indicate that a missing plane has not landed elsewhere; the third delayed the eventual search and rescue operation and the discovery of the plane wreckage, just miles away. The medical examiner's report was inconclusive; one report said that Hammarskjöld had died on impact; another stated that Hammarskjöld might have survived had rescue operations not been delayed.[3] The report also said that the chances of Sgt. Julien surviving the crash would have been "infinitely" better if the rescue operations had been hastened.[3]

On 16 March 2015, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon appointed members to an Independent Panel of Experts which will examine new information related to his death. The three member panel is led by Mohamed Chande Othman, the Chief Justice of Tanzania. The other two members are Kerryn Macaulay (Australia's representative to ICAO) and Henrik Larsen (a ballistics expert from the Danish National Police). It will submit its report by 30 June 2015.[8]

Alternative theories

Despite the multiple official inquiries that failed to find evidence of assassination, some continue to believe that the death of Hammarskjöld was not an accident.[2]

At the time of Hammarskjöld's death, U.S. and its allies' intelligence agencies were actively involved in the political situation in the Congo,[2] which culminated in Belgian and United States support for the secession of Katanga and the assassination of former prime minister Patrice Lumumba. Belgium and the United Kingdom had a vested interest in maintaining their control over much of the country's copper industry during the Congolese transition from colonialism to independence. Concerns about the nationalisation of the copper industry could have provided a financial incentive to remove either Lumumba or Hammarskjöld.[2]

The involvement of British officers in commanding the initial inquiries, which provided much of the information about the condition of the plane and the examination of the bodies, has led some to suggest a conflict of interest.[2][9] The official report dismissed a number of pieces of evidence that would have supported the view that Hammarskjöld was assassinated.[3] Some of these dismissals have been controversial, such as the conclusion that bullet wounds could have been caused by bullets exploding in a fire. Expert tests have questioned this conclusion, arguing that exploding bullets could not break the surface of the skin.[2][3] Major C. F. Westell, a ballistics authority, said, "I can certainly describe as sheer nonsense the statement that cartridges of machine guns or pistols detonated in a fire can penetrate a human body."[10] He based his statement on a large scale experiment that had been done to determine if military fire brigades would be in danger working near munitions depots. Other Swedish experts conducted and filmed tests showing that bullets heated to the point of explosion nonetheless did not achieve sufficient velocity to penetrate their box container.[10]

Sir Denis Wright, the then British ambassador to Ethiopia, in his annual report for 1961 establishes linkage of Hammarskjöld's death to British refusal to allow an Ethiopian military plane carrying troops destined to join the UN mission, landing at Entebbe and over-flying British-controlled Uganda to the Congo. Their refusal was only lifted after the death of the Secretary General. A Foreign Office official noting his comments on file, wrote affirming no "skeletons" in British cupboard and suggesting the Ambassador's comments should be removed from the final, official 'printed' version of the annual report.[11]

On 19 August 1998, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, chairman of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), stated that recently uncovered letters had implicated the British MI5, the American CIA, and then South African intelligence services in the crash.[12] One TRC letter said that a bomb in the aircraft's wheel bay was set to detonate when the wheels came down for a landing. Tutu said that they were unable to investigate the truth of the letters or the allegations that South Africa or Western intelligence agencies played a role in the crash. The British Foreign Office suggested that they may have been created as Soviet misinformation or disinformation.[13]

On 29 July 2005, Norwegian Major General Bjørn Egge gave an interview to the newspaper Aftenposten on the events surrounding Hammarskjöld's death. According to General Egge, who had been the first UN officer to see the body, Hammarskjöld had a hole in his forehead, and this hole was subsequently airbrushed from photos taken of the body. It appeared to Egge that Hammarskjöld had been thrown from the plane, and grass and leaves in his hands might indicate that he survived the crash – and that he had tried to scramble away from the wreckage. Egge does not claim directly that the wound was a gunshot wound.[14]

In his speech to the 64th session of the United Nations General Assembly on 23 September 2009, Colonel Gaddafi called upon the Libyan president of UNGA, Ali Treki, to institute a UN investigation into the deaths of Congolese prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, who was overthrown in 1960 and murdered the following year, and of UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld in 1961.[15]

According to a dozen witnesses interviewed by Swedish aid worker Göran Björkdahl in the 2000s (decade), Hammarskjöld's plane was shot down by another aircraft. Björkdahl also reviewed previously unavailable archive documents and internal UN communications. He believes that there was an intentional shootdown for the benefit of mining companies like Union Minière.[16][17][18] A US intelligence officer who was stationed at an electronic surveillance station in Cyprus stated that he heard a cockpit recording from Ndola. In the cockpit recording a pilot talks of closing in on the DC-6 in which Hammarskjöld was traveling, guns are heard firing, and then the words "I've hit it".[19]

In September 2013, a voluntary independent commission, headed by the British jurist Sir Stephen Sedley, released its review of information which had come to light in recent years, which concluded there was sufficient reason to revisit the investigation. It recommended that the United Nations reopen its inquiry "pursuant to General Assembly resolution 1759 (XVII) of 26 October 1962".[20] A key impetus for the commission was the publication of the book by Susan Williams, Who Killed Hammarskjöld?, https://books.google.com/books?id=LTYE2jmXiKAC which laid out the accumulation of alleged new evidence.[21]

In April 2014, The Guardian published evidence implicating Jan van Risseghem, a military pilot who served with the RAF during World War II, later with the Belgian Air Force and became famous as the pilot of Moise Tsjombé in Katanga. The article claims that an American NSA employee, former naval pilot Commander Charles Southall, working at the NSA listening station in Cyprus in 1961 shortly after midnight on the night of the crash, heard an intercept of a pilot's commentary in the air over Ndola – 3,000 miles away. Southall recalled the pilot saying: "I see a transport plane coming low. All the lights are on. I'm going down to make a run on it. Yes, it is the Transair DC-6. It's the plane," adding that his voice was "cool and professional". Then he heard the sound of gunfire and the pilot exclaiming: "I've hit it. There are flames! It's going down. It's crashing!" Based on aircraft registration and availability with the Katanga Air Force, registration KAT-93, a Fouga CM.170 Magister would be the most likely aircraft used and the website http://www.belgian-wings.be/ claims that van Risseghem piloted the Magisters for the KAF in 1961.[22][23]

Memorial

The Dag Hammarskjöld Crash Site Memorial is under consideration for inclusion as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A press release issued by the Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo stated that, "... in order to pay a tribute to this great man, now vanished from the scene, and to his colleagues, all of whom have fallen victim to the shameless intrigues of the great financial Powers of the West... the Government has decided to proclaim Tuesday, 19 September 1961, a day of national mourning."[1]

References

- 1 2 "Special Report on the Fatal Flight of the Secretary-General's Aircraft" (PDF). United Nations. 19 September 1961. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hollington, Kris (August 2008). Wolves, Jackals and Foxes. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-37899-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 United Nations General Assembly Session 17 Report of the Commission of investigation into the conditions and circumstances resulting in the tragic death of Mr Dag Hammarskjold and members of the party accompanying him. A/5069 24 April 1962. Retrieved 2008-11-21.(direct link: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-03-24.)

- ↑ Macarthur Job, Air Disaster Volume 4, Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd, 2001 ISBN 1-875671-48-X, p 142

- ↑ Lauria, Joe (19 May 2014). "U.N. Considers Reopening Probe into 1961 Crash that Killed Dag Hammarskjöld". Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "1961: UN Secretary General killed in air crash". BBC. 18 November 1961. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ↑ page 36 "The Spectator" 29 October 2011

- ↑ "UN announces members of panel probing new information on Dag Hammarskjöld death". UN News Centre. 16 March 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Matthew Hughes (9 August 2001). "The Man Who Killed Hammarskjöld?". London Review of Books. 23 (15): 33–34. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- 1 2 Arthur Gavshon (1962). The Mysterious Death of Dag Hammarskjold. New York: Walker and Company. p. 58.

- ↑ P R O FCO 31/165300 Ethiopia: Annual Review of 1961

- ↑ "Notes for Media Briefing By Archbishop" – by Desmond Tutu, Chairperson of the Truth And Reconciliation Commission – 19 August 1998 – http://www.info.gov.za/speeches/1998/98820_0x1539810364.htm

- ↑ "UN assassination plot denied," BBC World, 19 August 1998. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ↑ Cato Guhnfeldt (1970-01-01). "http://www.aftenposten.no/nyheter/iriks/article1087787.ece". Aftenposten.no. Retrieved 2013-09-10. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "Gaddafi's address to UN General Assembly". 23 September 2009.

- ↑ "Dag Hammarskjöld: evidence suggests UN chief's plane was shot down". The Guardian. 17 August 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ↑ I have no doubt Dag Hammarskjöld's plane was brought down, Göran Björkdahl, The Guardian, 2011 Aug 17

- ↑ Julian Borger, diplomatic editor (2011-09-16). "Call for new inquiry following emergence of new evidence". Guardian. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ↑ BBC News Magazine, 18 Sep 2–11, "Dag Hammarskjold: Was His Death a Crash or a Conspiracy?," http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-14913456

- ↑ "Dag Hammarskjold death: UN 'should reopen inquiry'". BBC News. September 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Background". The Hammarskjöld Commission.

- ↑ Borger, Julian (17 August 2011). "Dag Hammarskjöld: evidence suggests UN chief's plane was shot down". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ Borger, Julian (4 April 2014). "Dag Hammarskjöld's plane may have been shot down, ambassador warned". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

External links

- Dag Hammarskjöld archives on UN Archives website.

- 18 September 1961 UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld is killed and BBC

%2C_Bellomy-Lawson_Aviation_AN0199492.jpg)